Ecumenical Church Councils - Part 1

Mike Ervin

Ecumenical Church Councils - Part I

One of the subjects that received a number of votes form our last Open Forum was an interest from this class in learning more about the historic church councils that have occurred in the Christian faith through the ages.

And as usual in any deep look we take into Church history, we have to start by saying “it’s complicated.” Most Christians are only dimly aware of the history of church councils and in many cases, are not aware of exactly what they were and why they were held.

One of the reasons that Protestants are not that familiar with all the Church councils is that they are sometimes viewed as something those Roman Catholics do. And we Protestants don’t need to understand them. And frankly, there is some logic to that argument, because as you will see as we start to delve into this history, many of the later Councils were strongly focused on Roman Catholic issues. But as I think you will realize as we go through this study, many of the early Church councils reached conclusions that in many cases are fundamental to Protestants as well as Roman Catholics.

A further complication is, as I hope you appreciated from our recent short review of the Catholic Eastern Orthodox faith, there is another group that has a dog in this hunt, and that is the Eastern Orthodox church, that has its own very different views of which Church councils were important, and which ones were maybe irrelevant.

So, we will try today and next week to sort all of this out and hopefully come to a better understanding of the history of Church councils.

What Is A Church Council?

So let’s start with the obvious question – what is a Church Council. As usual there are as many definitions as there are theologians, but here is a fairy common one.

Church councils are formal meetings of bishops and representatives of several churches who are brought together to regulate points of doctrine or discipline. The meetings may be of a single ecclesiastical community or may involve an ecclesiastical province, a nation or other civil region, or the whole Church.

So right away we see that there can be both minor and major Church councils. We will only be addressing the major ones.

Ironically, one key to understanding the orthodox teachings of these councils is in relation to heresy. The councils, especially the earliest ones, were essentially anti-heresy conventions, called to sort the wheat of dogma from the chaff of heresy.

This could be a dizzying and disorderly process: no sooner had one bastion of orthodoxy had been defended, than the Church had to rush to the defense of another. So, while one council had to correct heretics who falsely divided Christ into two persons, the next council had to make a course correction in the other direction, reining in heretics who falsely united His human and divine natures into one.

How Many Major Church Councils Were There?

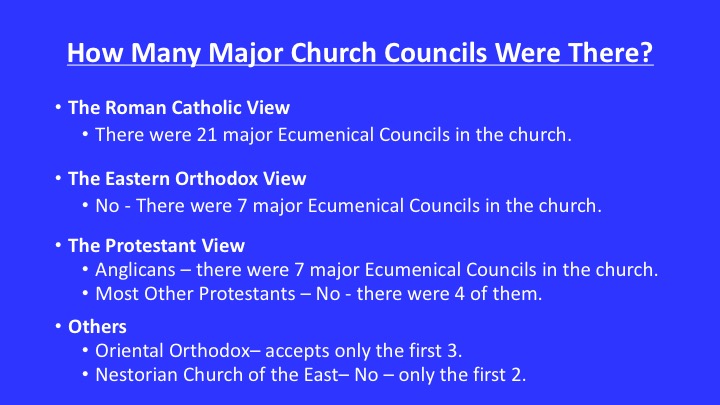

Well, again – it depends on who you talk to. As we go through this I will be giving you sort of three different views of how many Church Councils there were. We might call these the Roman Catholic View, the Eastern Orthodox View, and the Protestant view. There are actually more views than that, but we are going to try to keep it simple.

The Roman Catholic View

There were 21 major Ecumenical Councils in the church.

The Eastern Orthodox View

To the Eastern Orthodox Church there were 7 Church Councils that saved Christianity. They recognize there were others, but hold that they were not Ecumenical, thus they carry no weight.

The Protestant View

As a rough rule the Anglican church accepts the first 7 councils, and most other Protestants accept the first four as ecumenical.

Others

As a side note, The Oriental Orthodox

Church accepts only the first three Councils, and the Nestorian Church of the

East accepts only the first two.

But How Infallible are Ecumenical Councils?

The doctrine of the infallibility of ecumenical council’s states that solemn definitions of ecumenical councils, which concern faith or morals, and to which the whole Church must adhere, are infallible. Such decrees are often labeled as 'Canons' and they often have an attached anathema, a penalty of excommunication, against those who refuse to believe the teaching. The doctrine does not claim that every aspect of every ecumenical council is infallible.

Both the Eastern Orthodox and the Roman Catholic churches uphold versions of this doctrine. However, the Roman Catholic Church holds that solemn definitions of ecumenical councils meet the conditions of infallibility only when approved by the Pope, while the Eastern Orthodox Church holds that an ecumenical council is itself infallible when pronouncing on a specific matter.

Protestant churches would generally view ecumenical councils as fallible

human institutions that have no more than a derived authority to the extent

that they correctly expound Scripture (as most would generally consider

occurred with the first four councils in regard to their dogmatic decisions).

The Last Roman Councils

Before we do a deeper dive into the

crucial first seven councils of Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages, I would

like to briefly review the last 13 of the Councils that the Roman Catholic

Church considers ecumenical. Protestants do not relate to these because they

are often addressing issues with the Roman Church. But let’s try to broaden our

understanding by briefly reviewing what these were about.

In the high middle ages (1122-1514) there were five councils called the Lateran Councils. So named because they were held in the Lateran Palace in Rome.

First Council of the Lateran

As the German tribes continued to exert authority over the Holy Roman

Empire successors of Charlemagne insisted increasingly on the right

to appoint bishops on their own, which led to something called the Investiture

Controversy with the popes. The Concordat of Worms signed

by Pope Calixtus II included a compromise between the two parties, by

which the pope alone appoints bishops as spiritual head while the emperor

maintains a right to give secular offices and honors. Pope Calixtus invoked the

council to ratify this historic agreement. It met from March 18 to April

5, 1123. There are few documents and protocols left from the sessions and 25

canons approved.

Second Council of the Lateran

Pope Innocent II

After the death of Pope Honorius II (1124–1130), two popes were

elected by two groups of Cardinals. Sixteen cardinals elected Pope

Innocent II, while others elected Antipope Anacletus II who was

called the Pope of the Ghetto, in light of

his Jewish origins. Then Council deposed the antipope and his

followers. In important decisions regarding the celibacy of Catholic

priests, clerical marriages of priests and monks, which up to 1139 were

considered illegal, were defined and declared as non-existing and invalid. The

Council met under Pope Innocent II in April 1139 and issued 30 canons.

Third Council of the Lateran

The Council established the two-third majority necessary for the election of a pope. This two-third majority existed until Pope John Paul II. His change was reverted to the old two-third majority by Pope Benedict XVI in his Moto Proprio, De Aliquibus Mutationibus, from June 11, 2007. Still valid today are the regulations that outlawed simony, and the elevation to Episcopal offices for anyone under thirty. The council also ruled it illegal to sell arms or goods which could assist armaments to Muslim powers. Saracens and Jews were forbidden from keeping Christian slaves.

All Cathedrals were to appoint teachers for indigent and low-income children. Catharism was condemned as a heresy. This council is well documented: The council met in March 1179 in three sessions and issued 27 chapters, which were all approved by Pope Alexander III.

Catharism was a Christian dualist or Gnostic revival movement that thrived in some areas of Southern Europe, particularly northern Italy and what is now southern France, between the 12th and 14th centuries.

Fourth Council of the Lateran

The Council mandated every Christian to go at least once a year on Easter to confession and to receive the Holy Eucharist. The Council formally repeated Catholic teaching, that Christ is present in the Eucharist and thus clarified transubstantiation. It dealt with several heresies without naming names but intended to include the Catharists and several individual Catholic theologians. It made several political rulings as well. It met in only three sessions November 1215 under Pope Innocent III and issued 70 chapters.

First Council of Lyon

The Council continued the political rulings of the previous council by deposing Frederick II, as German king and as emperor. Frederick was accused of heresy, treason and arresting a ship with about 100 prelates willing to attend a meeting with the Pope. Frederick outlawed attendance at the council and blocked access to Lyon from Germany. Therefore the majority of council fathers originated from Spain, France and Italy. The Council met in three sessions from June 28, 1245 and issued 22 chapters all approved by Pope Innocent IV.

Second Council of Lyon

Pope Gregory X defined three aims for the council: aid to Jerusalem,

union with the Greek Orthodox Church and reform of the Catholic Church. The

council achieved a short-lived unity with the Greek representatives, who were

denounced for this back home by the hierarchy and the emperor. Papal

conclaves were regulated in Ubi periculum, which specified that

electors must be locked up during the conclave and, if they could not agree on

a pope after eight days, would receive water and bread

only. Franciscan, Dominican, and other orders had become

controversial in light of their increasing popularity. The Council confirmed

their privileges. Pope Gregory X approved all 31 chapters, after

modifying some of them, thus clearly indicating papal prerogatives. The Council

met in six sessions from May 7 to July 17, 1274 under his leadership.

Council of Vienne

Pope Clement V solemnly opened the council with a liturgy, which has been repeated since in all Catholic ecumenical councils. He entered the Cathedral in liturgical vestments with a small procession and took his place on the papal throne. Patriarchs, followed by Cardinals, archbishops and bishops were the next in rank. The Pope gave a blessing to the choir, which intoned the Veni Sancte Spiritus. The Pope issued a prayer to the Holy Spirit, the litany of saints was recited and only after additional prayer did the Pope actually address the Council and open it formally. He mentioned four topics, the Order of Knights Templar, the regaining of the Holy Land, a reform of public morality and freedom for the Church. Pope Clement had asked the bishops to list all their problems with the order.

The Templars had become an obstacle to many bishops because they could act

independently of them in such vital areas as filling parishes and other positions.

Many accusations against the order were not accepted as the Pope ruled

that confessions under torture were inadmissible. He withdrew

canonical support for the order but refused to turn over its properties to the

French king. The Council fathers discussed another crusade, but were

convinced instead by Raimundus Lullus that knowledge of foreign

languages is the only way to Christianize Muslims and Jews. He

successfully proposed the teaching of Greek, Hebrew, and Arabic

languages in Catholic universities. With this the council is

considered to have begun modern Catholic missionary policies. In the three

sessions, the council discussed further Franciscan poverty ideals. It met from

October 1311 until May 1312.

Conciliarism

The following councils in Constance, Basel, Ferrara, Florence witnessed an ongoing debate regarding the superiority of the papacy over ecumenical councils. Conciliarism was a reform movement in the 14th-, 15th- and 16th-century Catholic Church which held that supreme authority in the Church resided with an Ecumenical council, apart from, or even against, the pope.

Council of Constance

At the beginning of the Council there was the great schism, with three popes, each claiming legitimacy. One of them, John XXIII, called for the Council to take place in Konstance, Germany, hoping to get additional legitimation from the council. When public opinion moved against him in March 1415, he fled to Schaffhausen and went into hiding in several Black Forest villages such as Saig. After his flight, the Council issued the famous declaration Sacrosancta, which declared that any pope is below, not above, an ecumenical council. The council deposed all three popes and installed Pope Martin V, who made his peace with John XXIII by installing him as a cardinal.

Reforms did not materialize as hoped for, because the reformers disagreed among themselves. John Hus, a Bohemian reformer, was issued an imperial guarantee for safe conduct forth and back. The Church did not revoke its suspension to say Mass and preach in public. When Hus did just that, he was arrested and tried for heresy. Turned over to State authorities, he was burned at the stake in 1415. The Council of Constance was one of the longest lasting in Church history. The influx of 15,000 to 20,000 persons into the medieval city of 10,000 created inflation of unknown proportions. The German poet Oswald von Wolkenstein wrote: Just thinking of Constance, my purse begins to hurt. The Council addressed the future councils to be held and signed five concordats with the major participating nations. The Council met in 45 sessions from November 4, 1414 until April 22, 1418.

Councils of Basel, Ferrara and Florence

The council continued debate on Conciliarism. The papal delegate opened

the Council in Basel on July 23, 1431 without a single bishop present. When he

tried to close it later, bishops insisted of citing the pope to the Council,

which he refused. The Council continued on its own and issued several decrees

on Church reform. Most of the participants were theologians, bishops made only

ten percent of the eligible voters. The Pope moved the council to Ferrara,

where he achieved a major success, when the Greek Orthodox

Church agreed to unity with Rome. But Conciliarism continued to

be the politically correct trend, as “reform” and “council” were seen as

inseparable. Formally, the Council of Basel was never closed. The council

decreed in 1439 (a short-lived) union with Greek, Armenian, and Jacobite

Churches (1442). The Council had 25 sessions from July 1431 until April 1442 It

met under Pope Eugene IVin Basel, Germany, and Ferrara and Florence Italy.

It was moved to Rome in 1442.

Fifth Council of the Lateran

The Fifth Council of the Lateran opened under the leadership of the Pope in Rome. It issued a dogma that the soul of a human being lives forever. As previous councils, it condemned heresies stating the opposite without mentioning names. The opening sermon included the sentence: People must be transformed by holiness not holiness by the people. The issue was reform and numerous small reforms were approved by the council, such as selection of bishops, taxation issues, religious education, training of priests, improved sermons etc., but the larger issues were not covered and Pope Leo X was not particularly reform minded. The Council condemned as illegal a previous meeting in Pisa. The Council met from 1512–1517 in twelve sessions under Pope Julius II and his successor Pope Leo X.

Council of Trent

The council issued condemnations on what it defined as Protestant heresies and defined Church teachings in the areas of Scripture and Tradition, Original Sin, Justification, Sacraments, the Eucharist in Holy Mass and the veneration of saints. It issued numerous reform decrees. By specifying Catholic doctrine on salvation, the sacraments, and the Biblical canon, the Council was answering Protestant disputes. The Council entrusted to the Pope the implementation of its work, as a result of which Pope Pius V issued in 1566 the Roman Catechism, in 1568 a revised Roman Breviary, and in 1570 a revised Roman Missal, thus initiating the Tridentine Mass (from the city's Latinname Tridentum), and Pope Clement VIII issued in 1592 a revised edition of the Vulgate.

The Council of Trent is considered one of the most successful councils in the history of the Catholic Church, defining Church beliefs maintained today. It convened in Trent between December 13, 1545, and December 4, 1563 in twenty-five sessions for three periods. Council fathers met for the 1st–8th session in Trent (1545–1547), for the 9th–11th session in Bologna (1547) during the pontificate of Pope Paul III.[26] Under Pope Julius III, the council met in Trent (1551–1552) for the 12th–16th session. Under Pope Pius IV the 17th–25th session took place in Trent (1559–1565).

First Vatican Council

The Council was convened by Pope Pius IX in 1869 and had to be prematurely interrupted in 1870 because of advancing Italian troops. In the short time, it issued definitions of the Catholic faith, the papacy and the infallibility of the Pope. Many issues remained incomplete, such as a definition of the Church. Many French Catholics wished the dogmatization of Papal infallibility and the assumption of Mary in the ecumenical council. During Vatican One, nine mariological petitions favoured a possible assumption dogma, which however was strongly opposed by some council fathers, especially from Germany. On May 8, the fathers rejected a dogmatization at that time, a rejection shared by Pope Pius IX. The concept of Co-Redemptrix was also discussed but left open. In its support, Council fathers highlighted the divine motherhood of Mary and called her the mother of all graces. The council met in four sessions from December 8, 1869 to July 18, 1870.

Second Vatican Council

The Second Vatican Council was invoked by Pope John XXIII. It met from 1962 to 1965. Unlike most previous councils, this one did not discuss heresy as its orientation was mainly pastoral; The Council called for a renewal of the Roman rite of liturgy "according to the pristine norm of the Fathers" and a popularization of the Gregorian chant, pastoral decrees on the nature of the Church and its relation to the modern world, restoration of a theology of communion, promotion of Scripture and Biblical studies, pastoral decrees on the necessity of ecumenical progress towards reconciliation with other Christian churches.

The general sessions of the Council were held in the autumns of four successive years (in four periods) 1962 through 1965. During the other parts of the year special commissions met to review and collate the work of the bishops and to prepare for the next period. Sessions were held in Latin in St. Peter's Basilica, with secrecy kept as to discussions held and opinions expressed. Speeches (called interventions) were limited to ten minutes. Much of the work of the council, though, went on in a variety of other commission meetings (which could be held in other languages), as well as diverse informal meetings and social contacts outside of the council proper.

Two-thousand nine-hundred and eight (2,908) men (referred to as Council Fathers) were entitled to seats at the council. These included all bishops from around the world, as well as many superiors of male religious orders. 2,540 took part in the opening session, making it the largest gathering in any council in church history. (This compares to Vatican I where 737 attended, mostly from Europe. Attendance varied in later sessions from 2,100 to over 2,300. In addition, a varying number of periti (Latin for "experts") were available for theological consultation—a group that turned out to have a major influence as the council went forward. Seventeen Orthodox Churches and Protestant denominations sent observers. More than three dozen representatives of other Christian communities were present at the opening session, and the number grew to nearly 100 by the end of the 4th Council Session.

Next Week Preview

We have now reviewed the last 13 of the Church Councils. So now it is time to return to the key seven councils of Antiquity (c. 325 – 451).

- Nicaea I

- Constantinople I

- Ephesus

- Chalcedon

- Constantinople II

- Constantinople III

- Nicaea II

<< Audio >>