Studying Scripture

How is it done?

Studying scripture is what we do in our class. So we have been putting in a lot of effort in how we do that. And used different approaches. And have learned a lot as we have done that.

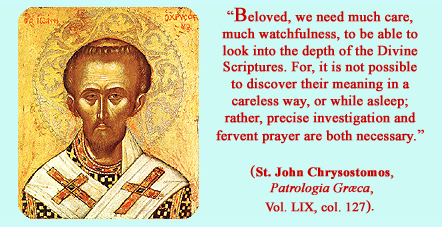

We have a quote at the bottom of our home page on the Third Well website as we went through a year long study experience:

The words of Torah are but its clothing; the guidance within them is the body. And as with a body, within that guidance breathes a soul that gives life.

We have used that quote over time as a constant reminder to not skim lightly over any piece of scripture without striving to dig deeper into possible meanings. And we discovered that it made all of our studying scripture more meaningful.

Studying Scripture and Biblical Interpretation

What we are talking about in studying scripture is interpretation. This is known technically as hermeneutics. One of the important principles in hermeneutics is context. This means that when studying scripture you should keep in mind not only the immediate context of the portion under study, but also other forms of context - cultural context - literary context and more. Not easy, but when you practice it more and more it starts to become second nature.

A simple example of applying context is to think about reading what comes before a passage being studied, what comes after, and what the Bible says as a whole about the topic being studied. More often than not, errors or difficulties of interpretation when studying the Bible come about as a result of not having a proper understanding of context.

Another aspect of Bible interpretation is not to interpret an elaborate theological or doctrinal teaching on the basis of an apparently obscure or isolated passage. If a passage or teaching is important, there are often multiple instances throughout the Bible where the topic is discussed more clearly. In such cases, looking at many parallel passages to understand a topic better is more helpful than fixating on a more obscure or difficult passage, when the answer to the issue at hand can usually be resolved by turning to clearer passages.

With regard to cultural context of the passage being studied, recognize that we are looking at biblical writings that are separated from our time by centuries – more than 1,950 years in the case of the New Testament and even longer in the case of the Hebrew bible. And written in ancient languages (ancient Hebrew and ancient Greek). And importantly, ancient Hebrew an Greek (and modern English) are idiomatic languages – and we do not know the idioms.

Hermeneutics & Studying Scripture

In the history of biblical interpretation, four major types of hermeneutics have emerged: the literal, moral, allegorical, and anagogical.

Literal interpretation asserts that a biblical text is to be interpreted according to the “plain meaning” conveyed by its grammatical construction and historical context. The literal meaning is held to correspond to the intention of the authors. This type of hermeneutics is often, but not necessarily, associated with belief in the verbal inspiration of the Bible. Extreme forms of this view are criticized on the ground that they do not account adequately for the evident individuality of style and vocabulary found in the various biblical authors. Another issue is that many who insist on studying scripture literally are trying to do so from English bibles, and the original bible was not in English. Linguists who know the ancient biblical languages insist that there is seldom one-to-one correspondence between English words and ancient biblical language words. Which is why there are so many different English translations of the bible.

Moral interpretation, which seeks to establish exegetical principles by which ethical lessons may be drawn from the various parts of the Bible.

Allegorical interpretation, a third type of hermeneutics, interprets the biblical narratives as having a second level of reference beyond those persons, things, and events explicitly mentioned in the text. A particular form of allegorical interpretation is the typological, according to which the key figures, main events, and principal institutions of the Old Testament are seen as “types” or foreshadowings of persons, events, and objects in the New Testament. According to this theory, interpretations such as that of Noah’s ark as a “type” of the Christian church have been intended by God from the beginning.

Philo of Alexandria, a Jewish philosopher and contemporary of Jesus, employed Platonic and Stoic categories to interpret the Jewish scriptures. His general practices were adopted by the Christian Clement of Alexandria, who sought the allegorical sense of biblical texts. Clement discovered deep philosophical truths in the plain-sounding narratives and precepts of the Bible. His successor, Origen, systematized these hermeneutical principles. Origen distinguished the literal, moral, and spiritual senses but acknowledged the spiritual to be the highest. In the middle ages, Origen’s threefold sense of scripture was expanded into a fourfold sense by a subdivision of the spiritual sense into the allegorical and the anagogical.

Anagogical, or mystical interpretation. This mode of interpretation seeks to explain biblical events as they relate to or prefigure the life to come. Probably one of the least used interpretive methods, but important to some.

Another, and somewhat simpler approach to interpretation that we used in one of our studies was to try to ask these three questions of each passage we are studying:

1. What was the author’s original intent, and how did his or her original audience understand the text?

2. How has the text been interpreted by the two faith communities who hold the bible to be sacred?

3. What might the text mean to me today?

Which of these techniques is best? All can be useful. We like to use the metaphor that looking at a text through different lenses gives us different insights into the underlying message.

So studying scripture is a serious business, but it is serious because it is important to most of us.

See other examples of some of our studying scripture in any of the links below.