Centering Prayer Introduction

Mike Ervin

Centering Prayer Introduction

The subject for today is Centering Prayer. Centering Prayer is something that some class members have asked me about – wondering if we could invite a speaker to tell us more about it.

Well, unfortunately for you that speaker will be me. Because I would very much like to talk about it.

Today’s class will be sort of a book report. There are a number of excellent books on centering prayer, I will mention three that I feel that give an excellent overview of what Centering Prayer is, how it was developed, and quite simply, how to do it.

The books are ”Centering Prayer and Inner Awakening” , written by one of the leading writers about Centering Prayer – Cynthia Bourgeault “Open Mind Open Heart” by Thomas Keating. And Centering Prayer by Basil Pennington.

Centering Prayer Introduction Books

These are the two books, or at least the covers. I can recommend both. But a lot of the material I will cover today is based on the first book. And it will be primarily from the first half of that book. Covering all of it cannot be done in one class. Still, the second book by Father Thomas Keating is a very good book also.

Centering Prayer is being taught internationally by an organization founded by Thomas Keating called Contemplative Outreach. I though it would be useful to start with their website and quote what they say about Centering Prayer.

Contemplative Outreach

Centering Prayer is a receptive method of Christian silent prayer which deepens our relationship with God, the indwelling presence … a prayer in which we can experience Gpd’s presence within us, closer than breathing, closer than thinking, closer than consciousness itself.

This method of prayer is both a relationship with God and a discipline to deepen that relationship.

We may think of prayer as thoughts or feelings expressed in words. But this is only one expression. In the Christian tradition contemplative prayer is considered to be the pure gift of God. It is the opening of mind and heart - our whole being - to God, the Ultimate Mystery, beyond thoughts, words, and emotions. Through grace we open our awareness to God whom we know by faith is within us, closer than breathing, closer than thinking, closer than choosing, closer than consciousness itself.

The Beginning – How Did It Start

It began at St. Joseph’s Abbey, a Trappist monastery in Spencer, Massachusetts. The abbot of this monastery was Father Thomas Keating.

A few miles from the monastery a former Catholic retreat house had been sold and reopened as the Insight Meditation Center. Rather quickly the monks of St. Joseph’s noticed an increase of young people stopping at their monastery asking for directions about how to get to the Insight Meditation Center.

Intrigued, Keating began to ask the young pilgrims what they were seeking, and the response was something like “A path, man, we are seeking a path”.

And upon learning that many of them had been raised as Christians, he asked them, “Why don’t you search for a path in your own tradition?” To which he received a genuinely astonished answer, “You mean Christianity has a path??”

The Beginning – How Did It Start (2)

Keating reported later that the young pilgrims knew instinctively what a “path” was: a meditation-based practice that changed the way you viewed reality and lived your life.

So, Keating took a question to his weekly gathering of his monastic community and asked: “Is it not possible to put the essence of the Christian contemplative path into a meditation method accessible to modern people living in the world?”

The monks knew full well that Christianity had a rich and deep contemplative path because they had been living it all of their adult lives. But how could they make a contemplative practice for non-monk seekers, who seemed to be defecting wholesale to eastern meditation practices.

One of the monks Father William Menninger, knew exactly where to look. And in “The Cloud of Unknowing”, a 14th century spiritual classic he found the instructions for this new prayer for modern people living in the world.

The Beginning – How Did It Start (3)

The Cloud of Unknowing (anonymous) was a prayer guidebook for how to achieve true contemplation. It was written in middle English and addressed to novices.

From that guidebook Menninger created the guidelines for what eventuaoly became Centering Prayer.

Beginning in about 1975, the monks began to offer this simple prayer at St. Joseph’s Abbey. In the beginning it was called “The Prayer of the Cloud”. But the phrase “Centering Prayer” caught on and and was used thereafter.

The practice caught on, particularly among lay people, and has grown steadily ever since. Today it is practiced worldwide, supported by an international membership network known as Contemplative Outreach, which provides regular opportunities for teaching and practice.

But was the 20th century really the beginning?

While ”The Cloud of Unknowing”

was the immediate source for Centering Prayer, the “Cloud” itself grew out of a stream of lived

tradition that preceded it by more than a thousand years.

Centering Prayer – And Christian Tradition

Centering Prayer, along with its sister discipline Christian Meditation, made its appearance in the modern Christian world in the mid 1970s.

Since this was also the era of that first grand arrival of Eastern spiritual paths on the North American shores you will sometimes hear the argument (mostly from Christians who were never exposed to contemplative prayer in the Christianity they grew up in) that meditation is not intrinsically Christian, but simply an effort to graft Eastern practices onto Western spirituality.

But I would like to like to counter-argue that this is false. There is a long historical association of contemplative practice in Christianity. Contemplative Christianity or Meditation is not a newfangled innovation , let alone a grafting of an alien tradition, but instead something that originally was at the very center of Christian practice and had become lost over the centuries.

Centering Prayer – And Christian Tradition

It is obviously impossible to overview the entire history of Christian spiritual practice. But the linage of Centering Prayer, from the head-waters in the spiritual teachings and practice of Jesus himself down into our own times, rests on two major steppingstones: the spiritual practice of the Desert Fathers and Mothers in the third through sixth centuries, and the Benedictine tradition of praying the scriptures known as Lectio Divina.

Let’s talk about Jesus first. Matters would be simple, if we could claim any clear scriptural references to substantiate that Jesus either practiced meditation or taught it. But we cannot.

It seems safe to assume Jesus was a contemplative though. At all of the great junctures of his life, the first temptation in the wilderness, his withdrawal to the far shores of the Galilee before the miracle of the loaves and fishes, his transfiguration on Mount Tabor, and at the final anguish in the Garden of Gethsemane – his pattern was always to withdraw in solitude to pray alone.

Jesus’s Teachings on Prayer

5 “When you pray, don’t be like hypocrites.

They love to pray standing in the synagogues and on the street corners so that people will see them. I assure you, that’s the only reward they’ll get.

6 But when you pray, go to your room, shut the door, and pray to your Father who is present in that secret place. Your Father who sees what you do in secret will reward you.”

But it is interesting that John Cassian (AD 365-423), the Christian Monk and Theologian who spent many years in the deserts of Egypt studying with the Desert Fathers and Mothers and was influential in bringing the ideas of Christian Mysticism to the West and transmitted much of that into the Benedictine order that spread across the West interpreted this instruction metaphorically to mean that when you pray to your Father in that secret place he was talking specifically about prayer hidden from the outer faculties, or ordinary awareness.

We will talk about those outer faculties and ordinary awareness a bit later.

Following Jesus into the Desert

By the early 4th century, as the Christian Church found itself catapulted from forbidden cult to imperial religion, a significant and growing remnant of Christians experienced this sudden catapult as posing a barrier to the authentic practice of the faith. They entered the deserts of Egypt and Syria in steady streams.

The so-called Desert Father’s and Desert Mother’s of those deserts stretched their activities from the 3rd to the 6th centuries AD and at one time totaled more than 20,000 Christians creating new ways to live contemplative lives.

Following Jesus into the Desert

The Desert Fathers were early Christian hermits, ascetics, and monks who lived mainly in the Scetes desert of Egypt beginning around the third century AD. The Apophthegmata Patrum is a collection of the wisdom of some of the early desert monks and nuns, in print as Sayings of the Desert Fathers. The most well known was Anthony the Great, who moved to the desert in AD 270–271 and became known as both the father and founder of desert monasticism. By the time Anthony died in AD 356, thousands of monks and nuns had been drawn to living in the desert following Anthony's example—his biographer, Athanasius of Alexandria, wrote that "the desert had become a city."

The Desert Fathers had a major influence on the development of Christianity.

The desert monastic communities that grew out of the informal gathering of hermit monks became the model for Christian monasticism. The eastern monastic tradition at Mount Athos and the western Rule of Saint Benedict both were strongly influenced by the traditions that began in the desert. All of the monastic revivals of the Middle Ages looked to the desert for inspiration and guidance. Much of Eastern Christian spirituality, including the Hesychast movement, had its roots in the practices of the Desert Fathers. Even religious renewals such as the German evangelicals and Pietists in Pennsylvania, the Devotio Moderna movement, and the Methodist Revival in England are seen by modern scholars as being influenced by the Desert Fathers.

Centering Prayer Overview

Understanding Centering Prayer

In Christian spiritual literature, Contemplative Prayer all too often has the aura of being an advanced and somewhat rarified form of prayer, mostly practiced by monks and mystics. But in essence, contemplative prayer is simply a wordless, trusting opening of yourself to God.

Far from being advanced, it is about the simplest form of prayer there is. As we grow up, our minds grow more complex. We spend so much of our adult energies thinking, planning, worrying, trying to get ahead or stay afloat, - yes it is a rat race, that we lose touch with that natural intimacy with God deep within us.

The gift of silence gradually recedes in the face of the demands of daily life, so that when we do re-encounter contemplative prayer as adults, it may seem like a strange and inaccessible inner terrain. But good things await there.

Centering Prayer – Cynthia’s Experience

The experience of a long-time practitioner of Centering Prayer is insightful.

“I have been a practitioner of Centering Prayer since 1988, and I can gratefully say it has changed my life and how I understand Christianity.

When I first encountered the practice, I had been an Episcopal Priest for 10 years, a great lover of the Christian mystical and inner traditions, and a veteran retreat-goer. But I was unable to establish a meditation practice, even though I tried. I hated to admit it but the process of trying to nail down and tether my mind, to focus it on a mantra, even the Jesus Prayer, brought up howls of inner resistance. I had pretty much given up.

Then I encountered Centering Prayer , and its uniquely forgiving starting point found my way into meditation at last. The practice took, and I have been with ever since.”

Centering Prayer Introduction

We suffer from outer noise and inner noise. But with some effort, we can stop the outer noise. Silent walks in the woods, Lenten and Advent quiet days at the local church, or a retreat at a monastery are wonderful ways of doing just that.

But stopping the inner noise is another matter. Even when the outer world has been wrestled into silence, we still go right on talking, worrying, arguing with ourselves, day-dreaming, and fantasizing about what may have happened, or what may happen. All of this results in a constant conversation in our heads.

To encounter those deeper reaches of our being, and silence that inner noise, what first seems to be needed is some sort of an interior on/off switch to tone down the inner talking as well. That’s probably the simplest way to picture what Centering Prayer is, and to describe its relationship to contemplative prayer or meditation.

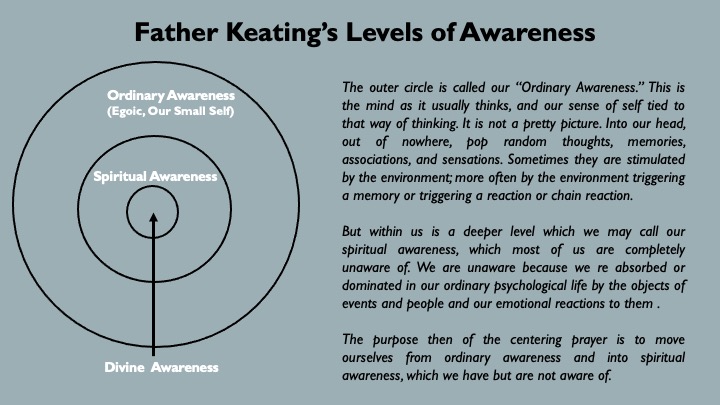

Father Keating’s Levels of Awareness

The outer circle is called our “Ordinary Awareness.” This is the mind as it usually thinks, and our sense of self tied to that way of thinking. it is not a pretty picture. Into our head, out of nowhere, pop random thoughts, memories, associations, and sensations. Sometimes they are stimulated by the environment; more often by the environment triggering a memory or triggering a reaction or chain reaction.

But within us is a deeper level which we may call our spiritual awareness, which most of us are completely unaware of. We are unaware because we re absorbed or dominated in our ordinary psychological life by the objects of events and people and our emotional reactions to them .

The purpose then of the centering prayer is to move ourselves from ordinary awareness and into spiritual awareness, which we have but are not aware of.

And the spiritual awareness draws from our divine awareness - the indwelling presence.

Martha and Mary

Another way of picturing this teaching on “levels of awareness” is to think of it in terms of the gospel story of Mary and Martha (Luke 10:38–41). This allows us to put a human face to each of these three levels of awareness and to observe some of the implications for our human interactions.

Jesus has been invited to dinner; and Martha, whom we’ll say is the embodiment of ordinary awareness, is doing all the things that are characteristic of ordinary awareness. She’s busy, she’s efficient, she’s getting the necessary tasks accomplished. She’s also, you may notice, stressed out, judgmental, self-righteousness, and not above manipulation if it suits her needs: “Lord, don’t you care that my sister has left me to do all the work by myself? Please tell her to help me.” You hear that self-pitying, self-meritorious voice so typical of ordinary awareness: “I’m doing something important and I want everybody to appreciate me.

Martha and Mary (2)

By contrast, we have spiritual awareness as embodied by Mary, who is simply sitting in complete, rapt attunement to the divine, indwelling presence: Jesus. The two of them, Mary and Jesus together, make a perfect picture of how spiritual awareness attends to the divine awareness. She’s at the feet of her lord; she’s in worship. For Mary, preparing dinner is not an issue; she’s already at the banquet table. It’s not that Martha is “wrong” and Mary is “right.” Both types of awareness are necessary for functioning in this world. But the idea in spiritual transformation is to integrate and reprioritize these levels so that our ordinary awareness is in alignment with and in service to our spiritual awareness (which in turn, as we have seen, is in service to the divine awareness)

In that alignment our being flows rightly, from innermost out. When something needs to be done in the outer world, we have sufficient ego strength to do it. But unlike ordinary awareness, which is always doing things to assert itself or fulfill itself, action grounded in our spiritual awareness merely flows out the divine abundance without regard to outcome or any need to draw attention to itself.

Centering Prayer Introduction - the Method

At root, it is a very simple method for reconnecting us with that natural aptitude for the inner life, that simplicity of our childhood, once our adult minds have become overly complex and busy. It’s very, very simple. You sit, comfortably and allow your heart to open toward that invisible but always present Origin of all that exists. Whenever a thought comes into your mind, you simply let the thought go and return to that open, silent attending upon the depths. Not because thinking is bad, but because it pulls you back to the surface of yourself, into ordinary awareness.

You use a short word or phrase, known as a “sacred word,” such as “abba” (Jesus’ own word for God) or “peace” or “be still” to help you let go of the thought promptly and cleanly. You do this practice for twenty minutes, a bit longer if you’d like, then you simply get up and move on with your life.

Centering Prayer Introduction

Ok, I said it is simple, let’s illustrate that by reading what Contemplative Outreach calls “The Four Guidelines of Centering Prayer”

1.Choose a sacred word as the symbol of your intention to consent to God’ s presence and action within.

2.Sitting comfortably and with eyes closed, settle briefly and slightly introduce the sacred word.

3.When engaged with you thoughts*, return ever-so-gently to the sacred word.

4. At the end of the prayer period, remain in silence with eyes closed for a couple of minutes.

* Thoughts include body sensations, feelings, images, worries, reflections, etc.

And then they elaborate a little (but not much) on each of the four.

The Official Instructions - I

I. Choose a sacred word as the symbol of your intention to consent to God’s presence and action within.

•The sacred word expresses our intention to consent to God’s presence and action within.

•Use a word of one or two syllables, such as: God, Jesus, Abba, Father, Mother, Mary, Amen. Other possibilities include Love, Listen, Peace, Mercy, Let Go, Silence, Stillness, Faith, Trust. But it is your choice.

•The sacred word is sacred not because of its inherent meaning, but because of the meaning we give it as the expression of our intention to consent.

•Having chosen a sacred word, we do not change it during the prayer period because that would be engaging thoughts.

The Official Instructions - II

II. Sitting comfortably and with eyes closed, settle briefly and silently introduce the sacred word as the symbol of your consent to God’s presence and action within.

•“Sitting comfortably” means relatively comfortably so as not to encourage sleep during the time of prayer. •

•Whatever sitting position we choose, we keep the back straight.

•We close our eyes as a symbol of letting go of what is going on around and within us.

•We introduce the sacred word inwardly as gently as laying a feather on a piece of absorbent cotton.

• If we fall sleep, we simply continue the prayer upon awakening.

The Official Instructions - III

III. When engaged with your thoughts, return ever-so-gently to the sacred word.

•“Thoughts” is an umbrella term for every perception, including body sensations, sense perceptions, feelings, images, memories, plans, reflections, concepts, commentaries, and spiritual experiences.

•Thoughts are an inevitable, integral and normal part of Centering Prayer. By “returning ever-so-gently to the sacred word” a minimum of effort is indicated. This is the only activity we initiate during the time of Centering Prayer.

•During the course of Centering Prayer, the sacred word may become vague or disappear.

The Official Instructions - IV

IV. At the end of the prayer period, remain in silence with eyes closed for a couple of minutes.

The additional two minutes enables us to bring the atmosphere of silence into everyday life.

A Few Things to Emphasize

•The instructions are designed to slow down the chatter of your ordinary

awareness. It is a prayer of silence. There are no words exchanged – either

way. It is a movement beyond conversation to communion with the divine.

• Regarding the “sacred” word – it is not sacred because of its inherent meaning, but because it expresses your intention to do the work. So, you may want to avoid a sacred word that is emotionally loaded for you.

• Regarding releasing thoughts – it means ALL thoughts, not just bad ones. You may occasionally experience a wonderful, beautiful, divine thought during the prayer. Simply release it.

Other Thoughts

What goes on in those silent depths during the time of Centering Prayer is no one’s business, not even your own; it is between your innermost being and God; that place where, as St. Augustine once said, “God is closer to your soul than you are yourself.”

Your own subjective experience of the prayer may be that nothing happened - except for the more-or-less continuous motion of letting go of thoughts. But in the depths of your being, in fact, plenty has been going on, and things are quietly but firmly being rearranged.

That interior rearrangement - or to give it a better name, that interior awakening - is the real business of Centering Prayer.

Outer Silence and Deeper Silence

The sixteenth-century mystic John of the Cross famously said “Silence is God’s first language,” And silence is the normal context in which contemplative prayer takes place. But as we discussed earlier, there is silence and then there is silence.

There is an outer silence, an outer stopping of the words and busy-ness, but there is also a much more challenging interior silence, where the inner talking stops as well. Most of us are familiar with this first kind of silence, although we don’t get enough of it because of the constant drama of our lives. It’s the kind of silence we normally practice going on a retreat. With a break from the usual hurly-burly of your life, you have time to draw inward and allow your mind to relax and ponder things. You may pore over a scriptural verse and let your imagination and feelings carry you more deeply into it. Or you may simply put the books away and go for a walk in the woods, allowing the tranquility of nature to bring you more deeply in touch with yourself.

Outer Silence and Deeper Silence

But there is another kind of silence as well, far less familiar to most Christians. In this other kind of silence, the drill is exactly the opposite. In dealing with outer silence, you encourage your mind to float where it will; but in dealing with this deeper silence, sometimes called “intentional silence”—or to use the generic description, meditation—a deliberate effort is made to restrain the wandering of the mind, either by 1) slowing down the thought process itself or 2) by developing a means of detaching oneself from it.

Intentional silence almost always feels like work. It doesn’t come naturally to most people, and there is in fact considerable resistance raised from the mind itself: “You mean I just sit there and make my mind a blank?” Then the inner talking begins in earnest, and you ask yourself, “How can this be prayer? How can God give me my imagination, reason, and feelings and then expect me not to use them?” “Where do ‘I’ go to if I stop thinking?” “Is it safe?”, "Will a blank mind let the devil in?"

Outer Silence and Deeper Silence

Since Centering Prayer is a discipline of intentional silence, dealing with this internal resistance is an inevitable part of developing a practice. In fact, I’ve often said to participants at Centering Prayer introductory workshops that ninety percent of the trick in successfully successfully establishing a practice lies in wanting to do it in the first place. So let’s consider that question first.

The Argument from Authority

Perhaps the most powerful argument is the one from authority. Virtually every spiritual tradition that holds a vision of human transformation at its heart also claims that a practice of intentional silence is non-negotiable. Period. You just have to do it. Whether it be the meditation of the yogic and Buddhist traditions, the zikr of the Sufis, the devekut of mystical Judaism, or the contemplative prayer of the Christians, there is a universal affirmation that this form of spiritual practice is essential to inner or spiritual awakening.

The Method of Centering Prayer

It has been said that ninety percent of the battle in establishing a regular discipline of meditation lies in wanting to do it in the first place. This chapter deals with the final ten percent.

Meditation, we’ve seen, is essentially about putting a stick into the spokes of our normal whirling wheel of thinking in order to break up the tyranny of the mind and the sense of selfhood that goes with it. Thomas Keating rather humorously describes the process as “taking a brief vacation from yourself.”

All meditation practices share this basic aim. But while their purpose remains similar, the strategies for achieving it vary considerably from method to method. Centering Prayer has a very distinct angle of approach, with some striking particularities that set it off from most other methods, no matter how superficially similar. It’s helpful to be aware of these particularities in advance, in order to sidestep some of the usual difficult spots in the practice and to avail oneself fully of its remarkable transformative effects.

The Method of Centering Prayer

Generally speaking, the various methodologies of meditation can be divided into three main groups: concentrative methods, awareness methods, and surrender methods.

Centering prayer belongs to this last (and least common) category.

Concentrative methods, which are probably the most universal and time-honored, rely on the principle of attention. In this type of meditation, the mind is given a simple task to focus its attention on—or more accurately, in. Depending on the tradition, this might involve counting one’s breaths, bringing attention to and then holding it on a particular area of the body (such as an arm or a leg); or, most commonly, reciting a mantra either aloud or silently.

A mantra is a word or short phrase of sacred origin and intent, used to collect the mind and invoke the divine presence. Some classic mantras, of course, include the great “Om padme” and “Gate, gate para gate” of the Eastern traditions, and the “La ilaha ill Allahu” (”there is nothing but God”) of Islamic tradition. But prayer with a mantra is also well attested in Christian tradition, including the Jesus prayer of the Christian Orthodox, the rosary, and the “Maranatha”—“Come, Lord”—recommended by John Main as the foundational mantra of Christian Meditation.

Attention and Intention (2)

A mantra is a word or short phrase of sacred origin and intent, used to collect the mind and invoke the divine presence. Prayer with a mantra is also well attested in Christian tradition, including the Jesus Prayer of the Christian Orthodox, the rosary of some Catholic practices.

Awareness methods (the second category), can be a little more difficult to understand, but involve creating in your mind an inner observer, that observes the stream of thoughts and and in a non-judgmental manner categorizes them to learn. Again you are given a task for your attention.

Surrender methods, such as Centering Prayer, attempt to simply release thoughts without focusing your attention on them.

Handling “Thoughts”

At this point in our exploration of Centering Prayer it might be helpful to introduce a pair of terms from the classic vocabulary of Christian spirituality that cover the ground we’ve just been over from a slightly different angle of vision. While they may initially sound formidable, I like them because once understood, they give an immediate and clear handle on what Centering Prayer is all about.

These words are cataphatic and apophatic. Cataphatic prayer (sometimes also spelled with a k: kataphatic) is prayer that makes use of what theologians call our “faculties.” It engages our reason, memory, imagination, feelings, and will. These, of course, are the normal human operating systems that connect us to the outer world and to our own interior life. They are the wonderful tools we have been given to make our way in this world and to experience it richly from the perspective of being a unique person with unique gifts to share and a unique relationship to God. Cataphatic prayer corresponds to what we have earlier described as our “ordinary awareness.” It emerges out of and reinforces that unique sense of egoic selfhood.

Handling “Thoughts” (2)

Apophatic prayer, by contrast, is prayer that does not make use of the faculties, in other words it bypasses our capacities for reason, imagination, visualization, emotion, and memory. We don’t need them in order to simply release every thought. In a sense it bypasses our usual mental processes which we tend to associate with our selfhood.

Centering Prayer clearly belongs to the generic category of apophatic prayer.

Why mention this? Because not understanding this can create significant objections to Centering Prayer. Our normal cataphatic mindset is what helps us deal with our “outer” world of ordinary awareness. What is wrong with that? Actually nothing. But apophatic prayer is targeted more at our spiritual awareness, that deeper well we are learning to explore.

Centering Prayer – A Final Thought

You sometimes hear that this kind of prayer is private or narcissistic, and from the outside it may look that way: each person sitting in their contemplative state, wrapped up in his or her personal silence.

The intent is not to escape into some private holiness trip, but to allow the Spirit to become more and more alive in us, more and more firmly rooted. Till at last, in the words of that remarkable prayer in Ephesians 3:16–19 (NIV), which is really the charter of contemplative prayer:

“I pray that out of his glorious riches He may strengthen you with power through his Spirit in your inner being so that Christ may dwell in your hearts through faith. And I pray that you, being rooted and grounded in love, may have power, together with all the saints, to grasp how wide and long and high and deep is the love of Christ, and to know this love that surpasses knowledge, that you may be filled with the very nature of God.”

That’s All Folks!

If you would like to “try” any organized Centering Prayer, Janis Claflin will be glad to help. She says anyone is welcome to join the Contemplative Gathering online on Wednesday from 6:30-7:15. They will be doing Lectio Divina and Centering Prayer .

If interested contact Janis at jcforpeace@gmail.com and request a zoom invitation.

See you next week.