Christian Martyrdom

Mike Ervin

Week I - Introduction to Christian Martyrdom

Christian Martyrdom

The purpose of the next two weeks of study is to examine the lives of two well-known western European Christian Martyrs of the 20th century – Dietrich Bonhoeffer and Maximillian Kolbe. They are both known for the stance they took against the Nazis and much has been written about them over the years. But as usual I would like to do a little more than that. we would be remiss in going straight to their stories without reviewing the long history of martyrdom in Christianity because it provides the context regarding how martyrdom has been such an important aspect of our faith. And it is quite an interesting story.

The Word

Many people have been killed for their faith through the ages. Interestingly, the word we use today to talk about someone who is killed for their beliefs, martyr, is the basic Greek word used in the New Testament which is translated “witness.” Therefore, when Jesus said, “ye shall be witnesses unto me” in Acts 1:8 it had great significance to them.

Acts:1:8. 8 Rather, you will receive power when the Holy Spirit has come upon you, and you will be my witnesses in Jerusalem, in all Judea and Samaria, and to the end of the earth.”

Jesus directed those comments to his immediate followers and early Christians who read this interpreted it as a warning that all of them might suffer martyrdom.

It should be noted that there are also arguments among scholars regarding who is a martyr and who is not. I am not going to get into those arguments. Many of them have to do with a strict interpretation that a martyr is someone who loses their life because they refuse to recant their faith. But many, many Christians have died in mass killings that are part of terrorist attacks or even in civil wars in dangerous societies, all because they were Christians. Again, we are not getting into those debates here. But we would like to spend some time to put martyrdom into context for those who have not studied it that much. Because quite frankly martyrdom was a “big deal” in the early church.

Early Christianity

It is first very important to understand how dramatic the growth of

Christianity In the first few centuries, Christianity grew quickly. Although it

was clearly a Jewish sect in its inception, by 100 A.D., it had become mostly

Gentile and had begun its break from its Jewish origins. By 200 A.D., the faith

had permeated most regions of the Roman Empire, though Christians were mostly

in the larger urban areas (Gaul, Lyons, Carthage, Rome). By 325, an estimated 7

million Christians were in the Empire and some outlying countries.

Why?

Why did it grow so fast compared to other religions in their formative years? Most scholars opine that this growth can be attributed to the new faith's meeting needs across cultural barriers, its giving general meaning to life for many, the overall transformation of those lives, the social concerns of Christians during the plagues for the sick and the poor, and the power of its doctrine. News of the resurrection of Christ produced great loyalty among followers. Christian martyrdom also, ironically, created vast interest in and respect for the Christians and increased their numbers.

So –

we have to ask –

how big a deal was

this. How

many martyrs were there?

How Many?

We mentioned that by 325 A.D. there were more than 7 million Christians.

But because of multiple persecutions during the first 3 centuries , by some estimates some 2 million Christians had been martyred by 325 AD, mostly by the Empire. It is important to understand though that estimates of martyrs are always suspect, and this one especially has been attacked by many scholars as an almost impossible number.

Tertuillian, (155-220 AD), a prolific early Christian writer is famous for his quote:

“The blood of the martyrs is the seed of the Church"

This quote, along with many other early writings in the church seemed to indicate that the early church leaders really believed that martyrdom itself was influential in the early growth of the church. And, as we will see, some Roman emperors began to believe the same thing.

But why and how were so many Christians killed? Many reasons.

Reasons for Persecutions

Sometimes local, socio-economic conflict with Jewish circles created persecution in the first century.

After A.D. 50, Christianity was put on the imperial list of "illicit" sects, and after A.D. 64, it was declared illegal, though this did not always result in continual persecution. Christians had many periods of nominal and benign neglect.

Christian refusal to worship or honor other gods was a source of great contention.

Finally Christians were accused of being atheists because of the denial of other gods and their refusal of emperor worship. Because of the latter they were accused of treason to the state, a capital crime.

The First Martyr

So – what set the tone for martyrdom in the early church?

According to Acts – the first martyr to the faith was Stephen. Stoned to death and forgiving his executioners in the same way Jesus forgave his.

Later in the book of Acts, the apostle Paul calls Stephen Jesus' martyr. It says in Acts 22:20. “When Stephen your witness was being killed, I stood there giving my approval, even watching the clothes that belonged to those who were killing him.”

And what about others?

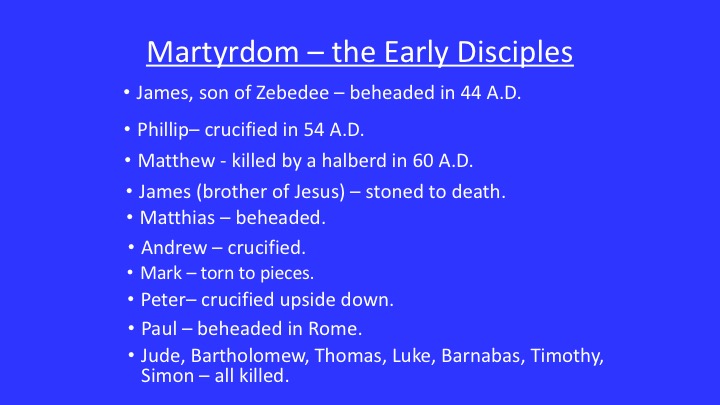

Martyrdom Among the Disciples

However, the history of Christian martyrs does not end with Stephen's death. During the first century after Jesus' death nearly all of his disciples suffered martyrdom for His sake. James the son of Zebedee was beheaded in approximately 44 A.D. Philip was crucified in 54 A.D. Matthew was killed with a halberd, an ax-like weapon, in 60 A.D. James, who is thought to be the brother of Jesus, was beaten to death, Matthias was beheaded, Andrew was crucified, Mark was torn to pieces, and Peter was crucified upside down. Jude, Bartholomew, and Thomas were also martyred. Paul suffered martyrdom in Rome where he was beheaded. Other early apostles Luke, Barnabas, Timothy, and Simon were also killed for the sake of Christ.

The Ongoing Saga

The history of Christian martyrs does not end with the death of the disciples. Thousands willingly gave their lives under Roman persecution by the emperors Nero, Domitian, Trajan, Marcus Aurelius, Maximus, Decius, Valerian, Aurelian, and Diocletian. The Roman persecution lasted well into the fourth century A.D. and did not end until Emperor Constantine declared Christianity the official religion of his empire.

Even after Constantine, in areas outside of the empire persecution continued In Persia, where the Gospel had quickly spread, many others were also martyred for their faith.

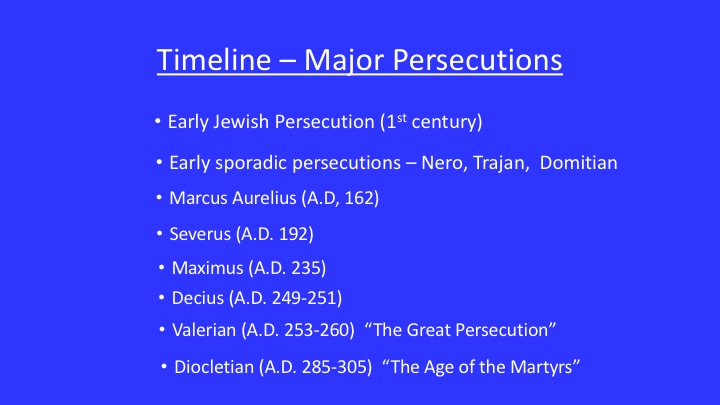

Timeline - Major Persecutions

Early Jewish Persecution (1st century)--cf. I Peter, Hebrews, and James.

Early Sporadic persecutions--Nero (A.D. 64); Domitian (A.D. 81-96); and Trajan (A.D. 108)

Marcus Aurelius (A.D.162)--The persecution of the Christians at Lyon is the most famous incident during his period.

Severus (A.D. 192)--Not everyone agrees that Severus himself was responsible for Christian persecutions. The most well-known incidents took places in North Africa, such as the executions of Perpetua and Felicity.

Maximus (A.D. 235)--Again, it is debated whether Maximus himself authorized these or whether they were the decisions of local governors. Several well-known Christian senators and leaders were executed during this time, while others such as Hippolytus were sent into exile.

Decius (A.D. 249-251) tried to force apostasy rather than create martyrdom. He created the libellus, a stamp of state approval given after swearing fealty to Caesar.

Valerian (A.D. 253-260) “The Great Persecution’ singled out bishops, forcing them to recant or die. He also kept Christians from meeting in cemeteries.

Diocletian (A.D. 285-305) "Age of the Martyrs”, known for evicting Christians from their homes, the army, and jobs. Christian churches and homes are burnt, copies of scriptures burnt, and Christian civil servants persecuted.

So how did Christian’s respond?

What Were the Responses?

The Apostates: Many left the faith.

The Lapsed: Some recanted under torture but returned later.

The Confessors: Those who endured persecution and lived to tell about it.

The Martyrs: Those who witnessed unto death.

Black Market: Some in wealthier families purchased the libellus on the black market.

The question of how the lapsed were to be restored to the Church was an important one with some demanding harsh penance and others wanting to extend the forgiveness and love of God.

So, there is no question that martyrdom was a real and integral part of the Christian experience in the early church.

Early Church View of Martyrdom

The early church's theology of martyrdom was born not in synods or councils, but in sunlit, blood-drenched coliseums and catacombs, dark and still as death. The word martyr means "witness" and is used as such throughout the New Testament. However, as the Roman Empire became increasingly hostile toward Christianity, the distinctions between witnessing and suffering became blurred and finally nonexistent.

In the second century, then, martyr became a technical term for a person who had died for Christ, while confessor was defined as one who proclaimed Christ's lordship at trial but did not suffer the death penalty.

Surprisingly perhaps, among early Christians becoming a martyr became much more honored than being a mere confessor.

Eusebius - describing the persecution at Lyon in 177 A.D.

Eusebius of Caesarea (circa 275 to 339) was bishop of Caesarea in Palestine and is often referred to as the father of church history because of his work in recording the history of the early Christian church. He was describing the great persecution of Christians at Lyon in the year 177. Lyon is in present day France.

"They were also so zealous in their imitation of Christ … that, though they had attained honor, and had borne witness, not once or twice, but many times—having been brought back to prison from the wild beasts, covered with burns and scars and wounds—yet they did not proclaim themselves martyrs, nor did they suffer us to address them by this name. If any one of us, in letter or conversation, spoke of them as martyrs, they rebuked him sharply.… And they reminded us of the martyrs who had already departed, and said, 'They are already martyrs whom Christ has deemed worthy to be taken up in their confession, having sealed their testimony by their departure; but we are lowly and humble confessors.' "

Roots of the Martyr Ideal

One hypothesis that has emerged is that the ideal of martyrdom did not originate with the Christian church; it was inspired by the passive resistance of pious Jews during the Maccabean revolt (173—164 B.C.). Antiochus IV, the tyrannical Seleucid king, ignited the revolution by a variety of barbarous acts, including banning Palestinian Jews from religious practices such as circumcision. Stories abounded of steadfast Jews, such as Eleazar the scribe (2 Macc. 6), who chose torture and death rather than violate the Law by eating pork. Two hundred years later, the Jewish War of A.D. 70 saw thousands become martyrs for their faith rather than capitulate to Roman paganism. This noble tradition helped shape the church's emerging theology of martyrdom.

Why Not Armed Resistance?

The Maccabean period also, however, gave stories of avenging rebels such as Judas Maccabeus. What prompted Christians to emulate the passive resisters such as Eleazar, rather than armed revolutionaries like Judas Maccabeus?

To answer this question one need look no further than to Jesus himself. The church understood martyrdom as an imitation of Christ. Jesus was the exemplar of nonviolence at his own trial and execution, declaring that his servants would not fight because his kingdom was not of this world.

Ongoing Martyrdom

Unfortunately, the history of Christian martyrs does not end with Constantine. Throughout the following centuries and up until present time, Christians have, and continue to, suffer martyrdom. This persecution has come by means of other Christians, other faiths, and political powers. This martyrdom gives testimony to the verse in John 15:20 where Jesus tells His disciples, "Remember the words I spoke to you: 'No servant is greater than his master.' If they persecuted me, they will persecute you also.

There were numerous other periods of high rates of martyrdom. We simply cannot count them all, but consider the Reformation era, which saw large number of Christians persecuted to the death by other Christians, with Catholics, Protestants, and Anabaptists pitted against each other.

We need to be very careful in reading accounts of the number of Christian Martyrs through history. The numbers are large – but they can be very inaccurate. So I am not going to give you any hard numbers. But it is still useful to review many of the horrible hotspots through history.

And In the 20th century, as world population increased exponentially the number of Christian deaths rose dramatically. Northern and Southern Africa, Middle East, Russia, China, Turkey, and others in various periods experienced millions of Christian deaths. Identifying actual martyrdom though was problematical, particularly in civil wars.

Conclusions?

What I have tried to present in this introductory part is something that many modern Christians, particularly in relatively prosperous and safe countries, may not be attuned to. Martyrdom in Christianity has always been a huge part of the Christian story. And that more so than any other major religion has been an integral part of what it meant to be a Christian.

Finally, we need to remind ourselves that unlike in the United States, the majority of Christians in the world live in very bad neighborhoods!

The Audio for Week I is here ------- Audio I

Week 2

We now proceed with lesson II of our two week exploration of Christian Martyrdom. This week we will be focusing on two 20th century Christian martyrs, both who suffered art the hands of the Nazis in World War II.

Before we do that, since some of you may have missed last week, I want to (in one quick slide) summarize what we concluded there.

Christian Martyrdom

Although the so-called age of martyrdom ended for Christians in the 4th century with the triumph of Christianity in the Roman Empire, there have been martyrs all over the world and in every age.

Over the centuries, many men and a few women who tried to bring Christianity to areas where it was not established have been martyred.

We find such people in Persia, central Europe, and Scandinavia as Christianity expanded beyond the frontiers of the Roman Empire.

Especially beginning in the 16th century, there have been martyrs in the New World, Africa, the Middle East, and Asia.

The Catholic Church has canonized groups of martyrs in Japan, China, Korea, Vietnam, and Uganda.

There have also been martyrs in Christian areas. During the Protestant Reformation, both Protestants and Catholics died at the hands of hostile Christians.

There were numerous deaths of clergy and laity in

repressive regimes, such as the Soviet Union and other countries of the Warsaw Pact, some of which we are just beginning to learn about.

Background: Christianity and the Nazis

To better understand what happened with Bonhoeffer we need to return to a not well-known aspect of the rise of Nazism and particularly of Adolph Hitler’s rise. So a short review of that history reveals, I think, what drove Bonhoeffer to so what he did.

We need to begin with some longer-term history as backdrop to Christianity in Germany.

You may remember when we reviewed the History of Christianity in the Reformation Era that after the many European Wars of Religion, a Peace Accord called the Treaty of Westphalia was signed in 1648. That treaty accorded the principle of cuius regio, eius religio to Catholicism, Lutheranism, and Calvinism. This Latin phrase is usually translated as: “Whose realm, his religion”. Meaning, the ruler of any religion gets to specify his religion.

The Protestant Church in Germany was and is divided into geographic regions and along denominational affiliations (Calvinist, Lutheran, and United churches). In the course of the 18th and 19th centuries, the then-existing monarchies and republics established regional churches (Landeskirchen), comprising the respective congregations within the then-existing state borders. In the case of Protestant ruling dynasties, each regional church affiliated with the regnal houses, and the crown provided financial and institutional support for its church. Church and State were, therefore, to a large extent combined on a regional basis.

Weimer Germany

In the aftermath of World War I, and the punitive punishments that Germany had to agree to – there was an extended period in which Germany lost most of its manufacturing businesses, experienced extreme economic hardships, and in general went into both political and social turmoil. Although the story is long and complex this led to extreme disentrancement among many Germans who wanted to return to their more glorious past. The National Socialism Party (Nazism) rose from this anger and disappointment.

Nazism subscribed to theories of racial hierarchy and Social Darwinism, identifying the Germans as a part of what the Nazis regarded as an Aryan or Nordic master race. It aimed to overcome social divisions and create a German homogeneous society based on racial purity which represented a people's community (Volksgemeinschaft). The Nazis aimed to unite all Germans living in historically German territory, as well as gain additional lands for German expansion under the doctrine of Lebensraum and exclude those who they deemed either community aliens or "inferior" races. The term "National Socialism" arose out of attempts to create a nationalist redefinition of "socialism", as an alternative to both international socialism and free market capitalism.

By the early 1920s, Adolf Hitler assumed control of the

organization and renamed it the National Socialist German Workers' Party to

broaden its appeal. The National Socialist Program was adopted in

1920 and called for a united Greater Germany that would deny

citizenship to Jews or those of Jewish descent, while also supporting

land reform and the nationalization of some industries. In Mein

Kampf (1924–1925), Hitler outlined the antisemitism

and anti-communism at the heart of his political philosophy, as well

as his disdain for parliamentary democracy and his belief in

Germany's right to territorial expansion.

German Christians

The German Christian movement in the Protestant Church developed in the late Weimar period. They were, for the most part, a "group of fanatic Nazi Protestants" who were organized in 1931 to help win elections of presbyters of the old-Prussian church.

There were several articulated goals of the German Christian movement:

- The de-emphasis of the Old Testament in Protestant theology.

- The removal of parts of the Old Testament deemed as too Jewish.

- Replacing the New Testament with a “dejudaized” version.

- Teach a different "heroic and militant" Jesus

- A high respect for secular authority over the one true Protestant church.

The Confessing Church

In response to these Nazi pressures a group of Protestant pastors organized the Pastors Emergency League to organize dissent against Nazi interference in church affairs.

Note that the emphasis of these Protestant pastors was a protest against secular interference in church affairs. Not a protest against the Nazi’s harsh stand against Jews.

In response to these Nazi pressures a group of Protestant pastors organized the Pastors Emergency League to organize dissent against Nazi interference in church affairs. This dissenting group eventually evolved into the Confessing Church.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer (4 February 1906 – 9 April 1945) was a German pastor, theologian, spy, anti-Nazi dissident, and key founding member of the Confessing Church. His writings on Christianity's role in the secular world have become widely influential, and his book The Cost of Discipleship has become a modern classic.

Apart from his theological writings, Bonhoeffer was known for his staunch resistance to Nazi dictatorship, including vocal opposition to Hitler's euthanasia program and genocidal persecution of the Jews.

Bonhoeffer attended the University of Berlin and completed his Doctor of theology degree at the young age of 24.

Studies in the United States

Still too young to be ordained, at the age of 24 Bonhoeffer went to the United States in 1930 for postgraduate study and a teaching fellowship at New York City's Union Theological Seminary.

Although Bonhoeffer found the American seminary not up to his exacting German standards ("There is no theology here."), he had life-changing experiences and friendships. He studied under Reinhold Niebuhr and met Frank Fisher, a black fellow-seminarian who introduced him to Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem, where Bonhoeffer taught Sunday school and formed a lifelong love for African-American spirituals, a collection of which he took back to Germany. He heard Adam Clayton Powell, Sr., preach the Gospel of Social Justice, and became sensitive not only to social injustices experienced by minorities, but also the ineptitude of the church to bring about integration.

Bonhoeffer began to see things "from below"—from the perspective of those who suffer oppression. He observed, "Here one can truly speak and hear about sin and grace and the love of God...the Black Christ is preached with rapturous passion and vision." Later Bonhoeffer referred to his impressions abroad as the point at which he "turned from phraseology to reality. He also learned to drive an automobile, although he failed the driving test three times. He traveled by car through the United States to Mexico, where he had been invited to speak on the subject of peace. His early visits to Italy, Libya, Spain, the United States, Mexico, and Cuba opened Bonhoeffer to ecumenism.

Career

After returning to Germany in 1931, Bonhoeffer became a lecturer in systematic theology at the University of Berlin. Deeply interested in ecumenism, he was appointed by the World Alliance for Promoting International Friendship through the Churches (a forerunner of the World Council of Churches) as one of its three European youth secretaries. At this time, he seems to have undergone something of a personal conversion from being a theologian primarily attracted to the intellectual side of Christianity to being a dedicated man of faith, resolved to carry out the teaching of Christ as he found it revealed in the Gospels. On 15 November 1931—at the age of 25—he was ordained at the Old-Prussian United St. Matthew's Church in Berlin.

Bonhoeffer's promising academic and ecclesiastical career was dramatically altered with Nazi ascension to power on 30 January 1933. He was a determined opponent of the regime from its first days. Two days after Hitler was installed as Chancellor, Bonhoeffer delivered a radio address in which he attacked Hitler and warned Germany against slipping into an idolatrous cult of the Führer (leader), who could very well turn out to be Verführer (mis-leader, or seducer). He was cut off the air in the middle of a sentence, though it is unclear whether the newly elected Nazi regime was responsible. In April 1933, Bonhoeffer raised the first voice for church resistance to Hitler's persecution of Jews, declaring that the church must not simply "bandage the victims under the wheel, but jam the spoke in the wheel itself."

In November 1932, two months before the Nazi takeover, there had been an election for presbyters and synodals (church officials) of the German Landeskirche (Protestant established churches). This election was marked by a struggle within the Old-Prussian Union Evangelical Church between the nationalistic German Christian (Deutsche Christen) movement and Young Reformers—a struggle which threatened to explode into schism. In July 1933, Hitler unconstitutionally imposed new church elections. Bonhoeffer put all his efforts into the election, campaigning for the selection of independent, non-Nazi officials.

Despite Bonhoeffer's efforts, in the rigged July election an overwhelming number of key church positions went to Nazi-supported Deutsche Christen people. The Deutsche Christen won a majority in the general synod of the Old-Prussian Union Evangelical Church and all its provincial synods except Westphalia, and in synods of all other Protestant church bodies, except for the Lutheran churches of Bavaria, Hanover, and Württemberg. The non-Nazi opposition regarded these bodies as uncorrupted "intact churches", as opposed to the other so-called "destroyed churches."

In opposition to Nazification, Bonhoeffer urged an interdict upon all pastoral services (baptisms, weddings, funerals, etc.), but Karl Barth and others advised against such a radical proposal. In August 1933, Bonhoeffer and Hermann Sasse were deputized by opposition church leaders to draft the Bethel Confession, a new statement of faith in opposition to the Deutsche Christen movement. Notable for affirming God's faithfulness to Jews as His chosen people, the Bethel Confession was so watered down to make it more palatable that Bonhoeffer ultimately refused to sign it.

In September 1933, the national church synod at Wittenberg voluntarily passed a resolution to apply the Aryan paragraph within the church, meaning that pastors and church officials of Jewish descent were to be removed from their posts. Regarding this as an affront to the principle of baptism, Martin Niemöller founded the Pfarrernotbund (Pastors' Emergency League). In November, a rally of 20,000 Deutsche Christens demanded the removal of the Old Testament from the Bible, which was seen by many as heresy, further swelling the ranks of the Emergency League.

Within weeks of its founding, more than a third of German pastors had joined the Emergency League. It was the forerunner of the Bekennende Kirche (Confessing Church), which aimed to preserve traditional Christian beliefs and practices. The Barmen Declaration, drafted by Barth in May 1934 and adopted by the Confessing Church, insisted that Christ, not the Führer, was the head of the church. The adoption of the declaration has often been viewed as a triumph, although by Wilhelm Niemöller's estimate, only 20% of German pastors were supporting the Confessing Church.

Ministries in London

When Bonhoeffer was offered a parish post in eastern Berlin in the autumn of 1933, he refused it in protest at the nationalist policy, and accepted a two-year appointment as a pastor of two German-speaking Protestant churches in London: the German Lutheran Church in Dacres Road, Sydenham. and the German Reformed Church of St Paul's, Goulston Street, Whitechapel.

He explained to Barth that he had found little support for his views—even among friends—and that "it was about time to go for a while into the desert," Barth regarded this as running away from real battle. He sharply rebuked Bonhoeffer, saying, "I can only reply to all the reasons and excuses which you put forward: 'And what of the German Church?'" Barth accused Bonhoeffer of abandoning his post and wasting his "splendid theological armory" while "the house of your church is on fire," and chided him to return to Berlin "by the next ship."

Bonhoeffer however did not go to England simply to avoid trouble at home; he hoped to put the ecumenical movement to work in the interest of the Confessing Church. He continued his involvement with the Confessing Church, running up a high telephone bill to maintain his contact with Martin Niemöller. In international gatherings, Bonhoeffer rallied people to oppose the Deutsche Christen movement and its attempt to amalgamate Nazi nationalism with the Christian gospel. When Bishop Theodor Heckel (de)—the official in charge of German Lutheran Church foreign affairs—traveled to London to warn Bonhoeffer to abstain from any ecumenical activity not directly authorized by Berlin, Bonhoeffer refused to abstain.

Underground Seminaries

In 1935, Bonhoeffer was presented with a much-sought-after opportunity to study non-violent resistance under Gandhi in his ashram, but, perhaps remembering Barth's rebuke, decided to return to Germany in order to head an underground seminary in Finkenwalde for training Confessing Church pastors.

As the Nazi suppression of the Confessing Church intensified, Barth was driven back to Switzerland in 1935; Niemöller was arrested in July 1937; and in August 1936, Bonhoeffer's authorization to teach at the University of Berlin was revoked after he was denounced as a "pacifist and enemy of the state" by Theodor Heckel.

Bonhoeffer's efforts for the underground seminaries included securing necessary funds. He found a great benefactor in Ruth von Kleist-Retzow. In times of trouble, Bonhoeffer's former students and their wives would take refuge in von Kleist-Retzow's Pomeranian estate, and Bonhoeffer was a frequent guest. Later he fell in love with Kleist-Retzow's granddaughter, Maria von Wedemeyer,[24] to whom he became engaged three months before his arrest. By August 1937, Himmler decreed the education and examination of Confessing Church ministry candidates illegal. In September 1937, the Gestapo closed the seminary at Finkenwalde, and by November arrested 27 pastors and former students. It was around this time that Bonhoeffer published his best-known book, The Cost of Discipleship, a study on the Sermon on the Mount, in which he not only attacked "cheap grace" as a cover for ethical laxity, but also preached "costly grace."

Bonhoeffer spent the next two years secretly traveling from one eastern German village to another to conduct "seminary on the run" supervision of his students, most of whom were working illegally in small parishes within the old-Prussian Ecclesiastical Province of Pomerania. The von Blumenthal family hosted the seminary on its estate of Groß Schlönwitz. The pastors of Groß Schlönwitz and neighbouring villages supported the education by employing and housing the students (among whom was Eberhard Bethge, who later edited Bonhoeffer's "Letters and Papers from Prison"), as vicars in their congregations.

In 1938, the Gestapo banned Bonhoeffer from Berlin. In summer 1939, the seminary was able to move to Sigurdshof, an outlying estate (Vorwerk) of the von Kleistfamily in Wendish Tychow. In March 1940, the Gestapo shut down the seminary there following the outbreak of World War II. Bonhoeffer's monastic communal life and teaching at Finkenwalde seminary formed the basis of his books, The Cost of Discipleship and Life Together.

Bonhoeffer's sister Sabine, along with her Jewish-classified husband Gerhard Leibholz and their two daughters, escaped to England by way of Switzerland in September 1940

Brief Return to the USA

It was at this juncture that Bonhoeffer left for the United States in June 1939 at the invitation of Union Theological Seminary in New York. Amid much inner turmoil, he soon regretted his decision despite strong pressures from his friends to stay in the United States.

He wrote to Reinhold Niebuhr: "I have come to the conclusion that I made a mistake in coming to America. I must live through this difficult period in our national history with the people of Germany. I will have no right to participate in the reconstruction of Christian life in Germany after the war if I do not share the trials of this time with my people... Christians in Germany will have to face the terrible alternative of either willing the defeat of their nation in order that Christian civilization may survive or willing the victory of their nation and thereby destroying civilization. I know which of these alternatives I must choose but I cannot make that choice from security.” He returned to Germany on the last scheduled steamer to cross the Atlantic.

Return to Germany

Back in Germany, Bonhoeffer was further harassed by the Nazi authorities as he was forbidden to speak in public and was required to regularly report his activities to the police. In 1941, he was forbidden to print or to publish.

In the meantime, Bonhoeffer joined the Abwehr (a German military intelligence organization). Dohnányi, already part of the Abwehr, brought him into the organization on the claim his wide ecumenical contacts would be of use to Germany, thus protecting him from conscription to active service. Bonhoeffer presumably knew about various 1943 plots against Hitler through Dohnányi, who was actively involved in the planning In the face of Nazi atrocities, the full scale of which Bonhoeffer learned through the Abwehr, he concluded that "the ultimate question for a responsible man to ask is not how he is to extricate himself heroically from the affair, but how the coming generation shall continue to live. "He did not justify his action but accepted that he was taking guilt upon himself as he wrote "when a man takes guilt upon himself in responsibility, he imputes his guilt to himself and no one else. He answers for it... Before other men he is justified by dire necessity; before himself he is acquitted by his conscience, but before God he hopes only for grace." (In a 1932 sermon, Bonhoeffer said: "the blood of martyrs might once again be demanded, but this blood, if we really have the courage and loyalty to shed it, will not be innocent, shining like that of the first witnesses for the faith. On our blood lies heavy guilt, the guilt of the unprofitable servant who is cast into outer darkness."

Under cover of the Abwehr, Bonhoeffer served as a courier for the German resistance movement to reveal its existence and intentions to the Western Allies in hope of garnering their support, and, through his ecumenical contacts abroad, to secure possible peace terms with the Allies for a post-Hitler government. His visits to Norway, Sweden, and Switzerland were camouflaged as legitimate intelligence activities for the Abwehr. In May 1942, he met Anglican Bishop George Bell of Chichester, a member of the House of Lords and an ally of the Confessing Church, contacted by Bonhoeffer's exiled brother-in-law Leibholz; through him feelers were sent to British foreign minister Anthony Eden. However, the British government ignored these, as it had all other approaches from the German resistance.

Dohnányi and Bonhoeffer were also involved in Abwehr operations to help German Jews escape to Switzerland. During this time Bonhoeffer worked on Ethics and wrote letters to keep up the spirits of his former students. He intended Ethics as his magnum opus, but it remained unfinished when he was arrested.

On 5 April 1943, Bonhoeffer and Dohnányi were arrested and imprisoned.

Imprisionment

After the failure of the 20 July Plot on Hitler's life in 1944 and the discovery in September 1944 of secret Abwehr documents relating to the conspiracy, Bonhoeffer was accused of association with the conspirators.

He was transferred from the military prison Tegel in Berlin, where he had been held for 18 months, to the detention cellar of the house prison of the Reich Security Head Office, the Gestapo's high-security prison. In February 1945, he was secretly moved to Buchenwald concentration camp, and finally to Flossenbürg concentration camp.

On 4 April 1945, the diaries of Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, head of the Abwehr, were discovered, and in a rage upon reading them, Hitler ordered that the Abwehr conspirators be executed. Bonhoeffer was led away just as he concluded his final Sunday service and asked an English prisoner, Payne Best, to remember him to Bishop George Bell of Chichester if he should ever reach his home: "This is the end—for me the beginning of life."

Bonhoeffer was condemned to death on 8 April 1945 by an SS judge at a drumhead court-martial without witnesses, or a defense. He was executed there by hanging at dawn on 9 April 1945, two weeks before soldiers from the United States 90th and 97th Infantry Divisions liberated the camp.

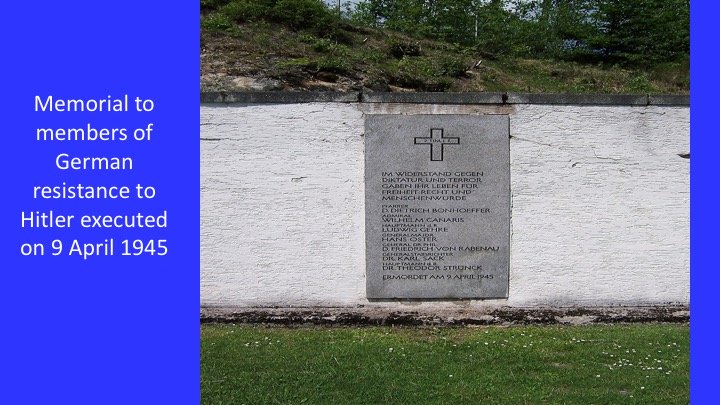

This is a memorial to the people hung that day. Bonhoeffer's name is the first on the list, followed by Admiral Canaris.

So –

by almost any definition of a martyr, Dietrich Bonhoeffer was a martyr. He knew his

life was in great danger every step of the way. And in his words the cost of

discipleship, and in living a life in imitating Christ was worth it. And he

paid for it with his life.

We Now Move on to Maximillian Kolbe

Maximilian Kolbe was born on 8 January 1894 in Zduńska Wola, in the Kingdom of Poland, which was a part of the Russian Empire, the second son of weaver Julius Kolbe and midwife Maria Dąbrowska. His father was an ethnic German and his mother was Polish. He had four brothers. Shortly after his birth, his family moved to Pabianice.

Kolbe's family was poor and he could not afford a university education. In 1907, Kolbe and his elder brother Francis joined the Conventual Franciscans. They enrolled at the Conventual Franciscan minor seminary in Lwow later that year. In 1910, Kolbe was allowed to enter the novitiate, where he was given the religious name Maximilian. He professed his first vows in 1911, and final vows in 1914, adopting the additional name of Maria (Mary).

This particular order in the Catholic church was strongly focused on ministering to the poor and the oppressed.

But the Franciscans sent Kolbe was sent to Rome in 1912, where he attended the Pontifical Gregorian University. He earned a doctorate in philosophy in 1919. From 1915 he continued his studies at the Pontifical University of St. Bonaventure where he earned a doctorate in theology in 1919 or 1922 (He was active in the consecration and entrustment to Mary.

In 1918, Kolbe was ordained a priest. In July 1919 he

returned to the newly independent Poland, where he was active in promoting

the veneration of the Immaculate Virgin Mary. He was strongly

opposed to leftist – in particular, communist – movements. From

1919 to 1922 he taught at the Kraków seminary. Around that time, as

well as earlier in Rome, he suffered from tuberculosis, which forced him

to take a lengthy leave of absence from his teaching duties. In January

1922, he founded the monthly periodical Rycerz Niepokalanej (Knight

of the Immaculate), a devotional publication based on French Le Messager

du Coeur de Jesus (Messenger of the Heart of Jesus). From 1922 to

1926 he operated a religious publishing press in Grodno. As his

activities grew in scope, in 1927 he founded a new Conventual Franciscan

monastery at Niepokalanów near Warsaw, which became a major religious

publishing center. A junior seminary was opened there two years later.

It is important to note that Kolbe's life was strongly influenced in

1906 by a childhood vision of the Virgin Mary. An intense interest in Mary formed the rest of his career.

Kolbe – Teacher, Writer, Publisher

In January 1922, he founded the monthly periodical Rycerz Niepokalanej (Knight of the Immaculate), a devotional publication.

From 1922 to 1926 he operated a religious publishing press in Grodno.

As his activities grew in scope, in 1927 he founded a new Conventual Franciscan monastery at Niepokalanów near Warsaw, which became a major religious publishing center.

Kolbe – Missions to East Asia

Between 1930 and 1936, Kolbe undertook a series of missions to East Asia.

At first, he arrived in Shanghai, China, but failed to gather a following there.

Next, he moved to Japan, where by 1931 he founded a monastery at the outskirts of Nagasaki and started publishing a Japanese edition of the Knight of the Immaculate.

The monastery he founded remains prominent in the Roman Catholic Church in Japan.

Kolbe – Return to Poland

Poor health forced Kolbe to return to Poland in 1936.

After the outbreak of World War II, which started with the invasion of Poland by Germany, Kolbe was one of the few brothers who remained in the monastery, where he organized a temporary hospital. He was once arrested (2 months), but released.

Upon his release he continued work at his monastery, where he and other monks provided shelter to refugees from Greater Poland, including 2,000 Jews whom he hid from German persecution.

On 17 February 1941, the monastery was shut down by German authorities. Kolbe and four others were arrested by the German Gestapo and transferred to Auschwitz.

Death at Auschwitz

Continuing to act as a priest, Kolbe was subjected to violent harassment, including beating and lashings.

At the end of July 1941, three prisoners disappeared from the camp, prompting the camp commander, to pick 10 men to be starved to death in an underground bunker to deter further escape attempts.

When one of the selected men, Franciszek Gajowniczek, cried out, "My wife! My children!", Kolbe volunteered to take his place.

After two weeks of dehydration and starvation, only Kolbe remained alive. The guards wanted the bunker emptied, so they gave Kolbe a lethal injection.

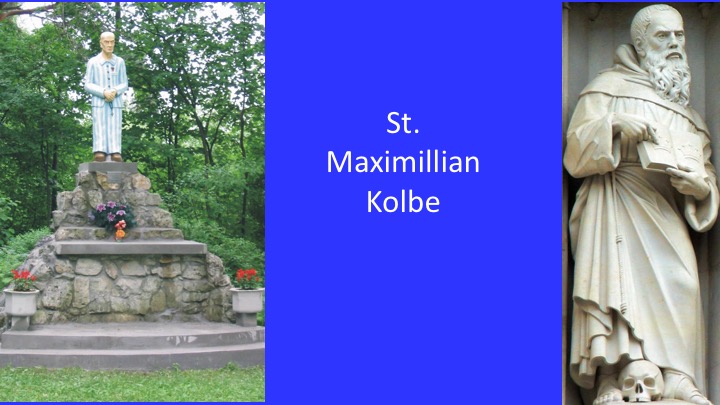

Saint Maximillian Kolbe

Mazimillian Kolbe was canonized as a saint in 1982 by Pope John Paul II.

At his canonization the Pope read Jesus' line in John 15:13

"Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends."

And the Pope went on to say:

"From today on the Church desires to address as Saint, a man who was granted the grace of carrying out the words of the Redeemer in an absolutely literal manner."

This (on the left) is a highly visited shrine in Poland.

In 1998 ten vacant statue niches on the façade above the Great West Door of Westminister Abby were filled with representative 20th-century Christian martyrs of various denominations. Those commemorated are Maximilian Kolbe, Manche Masemola, Janani Luwum, Grand Duchess Elizabeth of Russia, Martin Luther King Jr., Óscar Romero, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Esther John, Lucian Tapiedi, and Wang Zhiming. The statue on the right is of Kolbe.

The Audio for Week II is here ------- Audio II