Jesus and the Gospels Lesson 2

Mark I

Jesus and the Gospels

Engaging the Gospels as Literature

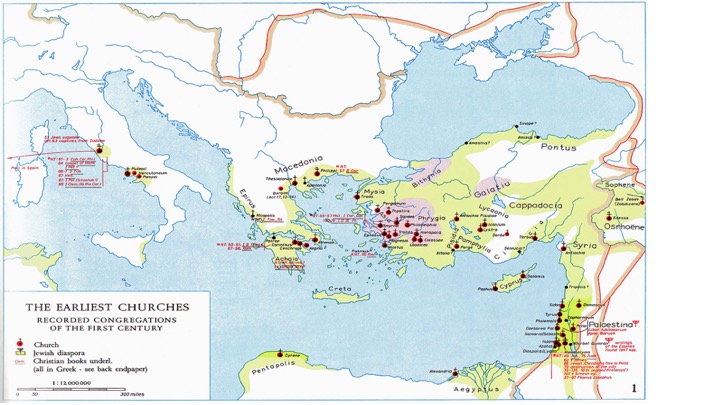

Initial Growth of Christian Churches

In our discussions two weeks ago we talked quite a bit about the matrix that early Christianity developed in.

And the many Christian assemblies that spread across the Mediterranean well before the Gospels were composed.

And most New Testament scholars have surmised that the four Gospel writers probably lived in four different communities on this map, most likely somewhere in the Jewish Diaspora, indicated by the light green part of the map.

Jesus and the Gospels

What is this approach to the Gospels all about?

Many of us have been reading the Gospels all of our adult life.

But there are many ways to do this. And reading in different ways almost always results in new insights.

We experienced this in this class about 6 years ago when we did a 12 week deep dive into the book of Genesis.

Since Genesis was the first prose religious writing written we decided to read through Genesis in 12 weeks and to read it as literature to see if we could see why it was put together the way it was. What was the overall plot, how was it presented, etc.

•And many of us, especially the teacher, came away from that with a completely new appreciation of Genesis.

The Gospel of Mark

Let’s start with some general considerations of how you might want to read the Gospels if you want to understand them as literature.

Most Christians read the Gospels in a very focused way. Picking out a few verses as part of a study of a particular topic, and using those verses to try to prove a particular belief or doctrine. In other words they are not reading them as literature.

It is quite remarkable that few of us every experienced the Gospels as literature. And most of us have never experienced any book of the Bible by reading it straightforward from beginning to end.

The Gospels as Literature

We said in our introductory material that we were going to try to interpret the Gospels using literary engagement.

The approach we will use is to try to engage these ancient sources as literature, rather than disassembling the Gospels in the search for earlier sources.

We are, in short, going to acknowledge that the Gospels are written from the perspective of the resurrection faith. All of the writers were insiders.

Each of the Gospel writers had their own sense of Jesus’s identity and self-understanding, a grasp of the meaning of his life.

But we are not going to view that as a weakness, but a strength. If each of these writers had a slightly different understanding of Jesus and the meaning of the resurrection, then we can learn much by trying to interpret their views through the way they told the story, and it is our responsibility as serious Christians to meld them into our understanding.

Our Approach – A Disclaimer

We are going to engage the Gospels as literature.

But we will not do the analysis ourselves, because it is a daunting task.

Instead we will be reviewing how modern New Testament scholars have used literary engagement to develop new insights into the Gospels.

As we travel through this study of the Gospels I will frequently be presenting opinions that are called the consensus views of New Testament scholars.

And when we say New Testament Scholars we are talking both about the scholars at seminaries and academic institutions around the world.

As we review these be aware that my disclaimer is that consensus does not mean 100%. There are always dissenting views.

Example Consensus Views

Let’s talk about a first consensus view from these scholars.

The consensus view of modern scholars is that we do not know who the authors of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John are, nor where they lived.

All of the Gospels were originally written anonymously, they did not reveal who wrote them. The titles we see in our modern bibles come from early church tradition. And that tradition tried to connect the Gospels to the original Apostles in some way.

Another current (consensus) understanding – that Mark was written first – is a relatively recent consensus – it came from scholars in the 18th century.

The “traditional” view before that was that Matthew was first.

The Gospels – Dating

The Gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke show dramatic similarities. When displayed in three columns, with Matthew on the left, Mark in the middle, and Luke on the right (Gospel Parallels Throckmorton), it becomes apparent that there is a significant relationship between the Gospels.

They frequently describe the same events, have events in the same order, and use the same wording in a way that implies written dependence rather than oral dependence.

Understanding the source of these similarities is referred to as the synoptic problem.

Synoptic is a Greek word meaning “seen together”.

Solving the synoptic problem turned out to be a formidable problem but eventually resulted in a solution that Mark was actually the first published Gospel and that Matthew and Luke later copied Mark and added their own material to it.

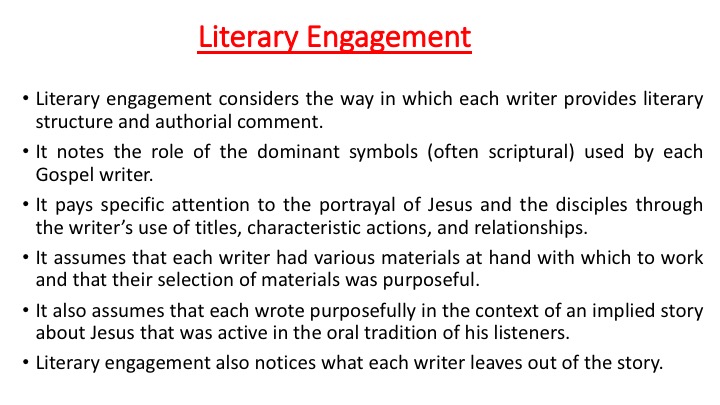

Literary Engagement

Literary

engagement considers the way in which each writer provides literary structure

and authorial comment.

It notes the role of the dominant symbols (often scriptural) used by each Gospel writer.

It pays specific attention to the portrayal of Jesus and the disciples through the writer’s use of titles, characteristic actions, and relationships.

It assumes that each writer had various materials at hand with which to work and that their selection of materials was purposeful.

It also assumes that each wrote purposefully in the context of an implied story about Jesus that was active in the oral tradition of his listeners.

Literary engagement also notices what each writer leaves out of the story.

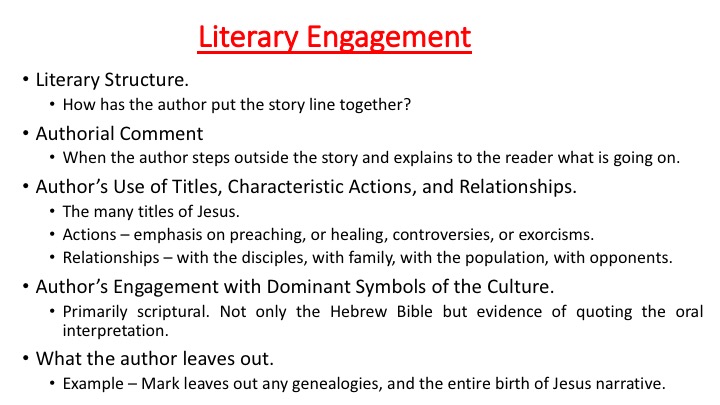

Literary Engagement

Literary Structure.

- How has the author put the story line together?

Authorial Comment

- When the author steps outside the story and explains to the reader what is going on.

Author’s Use of Titles, Characteristic Actions, and Relationships.

- The many titles of Jesus.

- Actions – emphasis on preaching, or healing, controversies, or exorcisms.

- Relationships – with the disciples, with family, with the population, with opponents.

Author’s Engagement with Dominant Symbols of the Culture.

- Primarily scriptural. Not only the Hebrew Bible but evidence of quoting the oral interpretation.

What the author leaves out.

- Example – Mark leaves out any genealogies, and the entire birth of Jesus narrative.

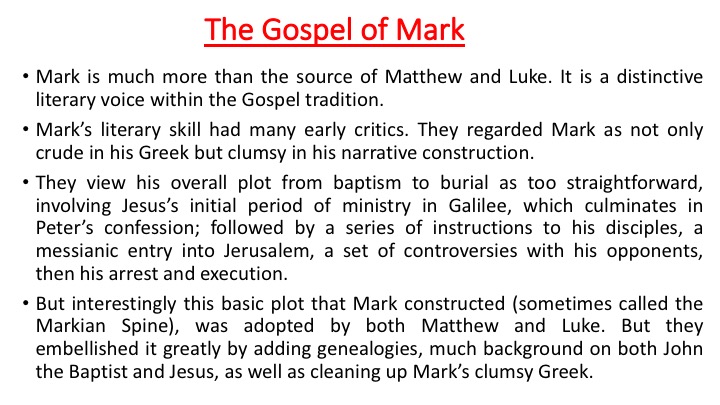

The Gospel of Mark

Mark is much more than the source of Matthew and Luke. It is a distinctive literary voice within the Gospel tradition.

Mark’s literary skill has critics and admirers. Some observers regard Mark as not only crude in his Greek but clumsy in his narrative construction.

They view his overall plot from baptism to burial as straightforward, involving Jesus’s initial period of ministry in Galilee, which culminates in Peter’s confession; followed by a series of instructions to his disciples, a messianic entry into Jerusalem, a set of controversies with his opponents, then his arrest and execution.

But interestingly this basic plot that Mark constructed (sometimes called the Markian Spine), was adopted by both Matthew and Luke. But they embellished it greatly by adding genealogies, much background on both John the Baptist and Jesus, as well as cleaning up Mark’s clumsy Greek.

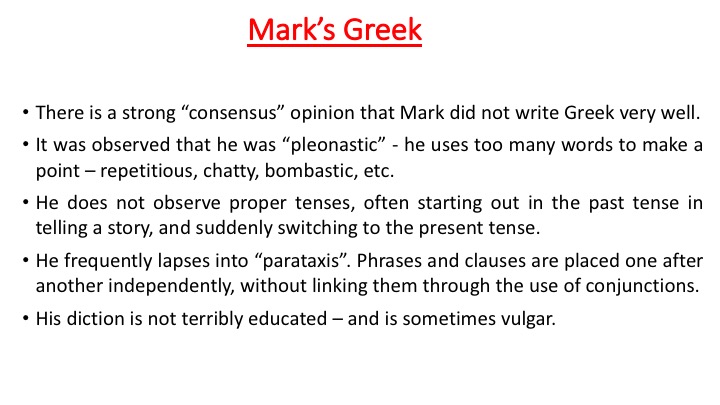

Mark’s Greek

There is a strong “consensus” opinion that Mark did not write Greek very well.

It was observed that he was “pleonastic” - he uses too many words to make a point – repetitious, chatty, bombastic, etc.

He does not observe proper tenses, often starting out in the past tense in telling a story, and suddenly switching to the present tense.

He frequently lapses into “parataxis”. Phrases and clauses are placed one after another independently, without linking them through the use of conjunctions.

His diction is not terribly educated – and is sometimes vulgar.

But – Wait a Minute!

Wait – I have read Mark for years – he does not write that badly!

And you are right. You are reading Mark in good English, not bad Greek.

Englishing the Bible led to the beautiful ”Biblical English” of William Tyndale in the 16th century. Tyndale “fixed” all of the weaknesses of Mark’s Greek.

And in the fourth century Jerome translated the Gospels from the Greek into classical Latin. This became the Vulgate – the Bible for Roman Catholics.

How Does Mark Portray Jesus?

In Mark’s Gospel, Jesus is not the nice Jewish boy down the street. He is not a simple teacher. He consistently, all through the early part of this Gospel is entering into cosmic conflict with demons, all of whom he conquers. We talked earlier about which aspect of Jesus actions are emphasized – his teaching, his healing, his controversies, or his exorcisms.

Mark emphasizes exorcisms – to show Jesus’s great power over evil.

And yet Jesus is later portrayed as a human one who submits to great suffering and eventual execution.

And so Mark’s portrayal of Jesus is deliberately very complex – both very powerful yet profoundly weak.

Mark’s Apocalyptic Chapter

We should not move on to more of Mark next week without discussing Chapter 13. Jewish apocalyptic literature thrived from the period of the Maccabees (~165 BC) well into New Testament times.

The book of Daniel in chapters 7-12 presents an elaborate apocalyptic picture of the future which may have been written during the Maccabean period. There are snippets of apocalyptic writings in Paul in I and II Thessalonians and of course Revelations is pure apocalyptic and is often called the Apocalypse.

In the section of Mark that is now Chapter 13 Mark presents an elaborate apocalyptic view of the future – all from the lips of Jesus. Many scholars now refer to it as the little Apocalypse.

In it Jesus predicts the destruction of the temple and then talks of a coming of the Son of Man with great power and glory. Those words are right out of Daniel chapter 7.

Who Knows What in the Gospel of Mark?

God and the readers knows that Jesus is God’s son. Mark 1:11

The evil spirits and demons know that Jesus is God’s son. Mark 3:11

Jesus’s executioner knows that Jesus is God’s son. Mark 15:39

But the disciples seem clueless. Peter finally recognizes Jesus as Messiah in Mark 8, but later denies Jesus in Mark 14.

So Jesus is rejected by the leaders of the people, and his followers. He is misunderstood, rejected, and abandoned.

Such is the teaching of Mark.

Next Week – More Mark

Teacher and Disciples

Passion and Death