Examining the New Testament Lesson 2 First 7 Letters of Paul

A Panoramic View of the New Testament

(In

Three Weeks)

Today is Week 2

Examining the New Testament Lesson 2

Links

< Home Page> < Examining N.T. Menu > < Top of Page >

The Text

A Panoramic View of the New Testament (In Three Weeks)

Today is Week 2

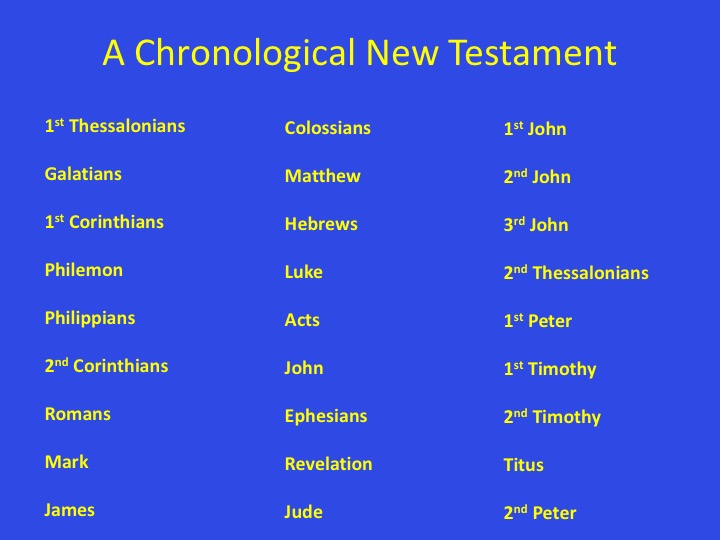

OK - we promised this week to show you the chronological New Testament that we will review and here it is. 27 documents, but in an entirely different sequence, based on scholarly guesstimates of when each was written. The first point I want to make is that this listing is almost certainly wrong. One of the many things that were different in biblical times than in our 21st century culture is that (for some reason) none of these documents were dated by the authors (???). So, much scholarly research has been done to try to pin that down. But it is a tough job and all scholars that do this work acknowledge that it is a tough job. After reviewing a lot of it I have put his one together. I think it represents a pretty good approximation of a chronological New Testament.

1st Thessalonians

The very first document in our chronological NT is Paul’s letter to a Christ community in Thessalonica, the capital city of Macedonia (Northern Greece). Somewhat surprisingly, given the movement’s origin among Jews in the Jewish homeland, the earliest Christian document is written to a community in Europe, which was largely Gentile.

There, according to Acts, Paul went to the synagogue and converted some Jews and “a great many of the devout Greeks” (Gentile “God-lovers,” 17.4).

From the letter itself, we learn that while in Athens Paul sent his companion Timothy back to Thessalonica to find out how the community was doing (2.17–3.6). Timothy returned to Paul, with news of the community.

1st Thessalonians (2)

First Thessalonians is Paul’s response to what he heard from Timothy. It follows the standard form of a Greek letter, as all of Paul’s letters do: sender’s name first, then the addressee, a brief greeting (often a blessing), a thanksgiving, the body of the letter, and the closing.

Paul, responding to Timothy’s report, wants to maintain his relationship with the community. It is full of gratitude and affection. Paul reminisces about his time with the Thessalonians and how he has longed to see them.

With one exception, texts in this letter have had little theological significance in Christian history.

1st Thessalonians (3)

For the last century or so, one text has been important to two very different groups. For millions of Christians, mostly in independent Protestant churches, the text is one of the foundations of “rapture theology.” This is the belief that true believers will be raptured from the earth seven years before the second coming of Jesus. They will be spared the suffering—the trials and tribulations, plagues and wars and famines—that will engulf those left behind. The “rapture” is the premise of the recent bestselling Left Behind novels.

Rapture theology is almost always accompanied by the claim that the second coming of Jesus will be soon. Polls suggest that around 40 percent of American Christians believe that it will happen in the next fifty years. Most do so because they belong to churches that teach this.

The text is also important for mainstream biblical scholars. It is one of the reasons for the conclusion that Paul (and many early followers of Jesus) expected the second coming of Jesus soon relative to their point in time. The expectation was obviously wrong—it didn’t happen.

1st Thessalonians (4)

The “rapture” text is in 4:13-18

“But we do not want you to be uninformed, brothers and sisters, about those who have died, so that you may not grieve as others do who have no hope. For since we believe that Jesus died and rose again, even so, through Jesus, God will bring with him those who have died. For this we declare to you by the word of the Lord, that we who are alive, who are left until the coming of the Lord, will by no means precede those who have died. For the Lord himself, with a cry of command, with the archangel’s call and with the sound of God’s trumpet, will descend from heaven, and the dead in Christ will rise first. Then we who are alive, who are left, will be caught up in the clouds together with them to meet the Lord in the air; and so we will be with the Lord forever. Therefore encourage one another with these words.”

The Rapture in Historical Context

Seeing this text in its ancient historical context dissolves a foundation of rapture theology. Paul was not providing detailed information about a second coming that is still future from our point in time, whose details are to be correlated with other biblical texts about the “last things”—the second coming, last judgment, and final state of affairs.

But it is clear that the text in its historical context meant that Paul did think the second coming would be soon. He distinguished between “those who have died” and “we who are alive, who are left” when the Lord comes again. These words most naturally mean that Paul expected the second coming to occur while some of those he was writing to were still alive, including possibly himself.

Paul makes a similar distinction in 1 Corinthians 15.51–52: “Listen, I will tell you a mystery! We will not all die, but we will all be changed,”

Galatians

No other relatively short New Testament document has had as much influence on Christian theology as Galatians. Its language of “justification” and the contrasts between “grace” and “law” and “faith” and “works” were central to Martin Luther’s thought and have been for Protestants ever since. Though Paul also used this language in his letter to Christ-communities in Rome a half decade or so later, it first appears in Galatians.

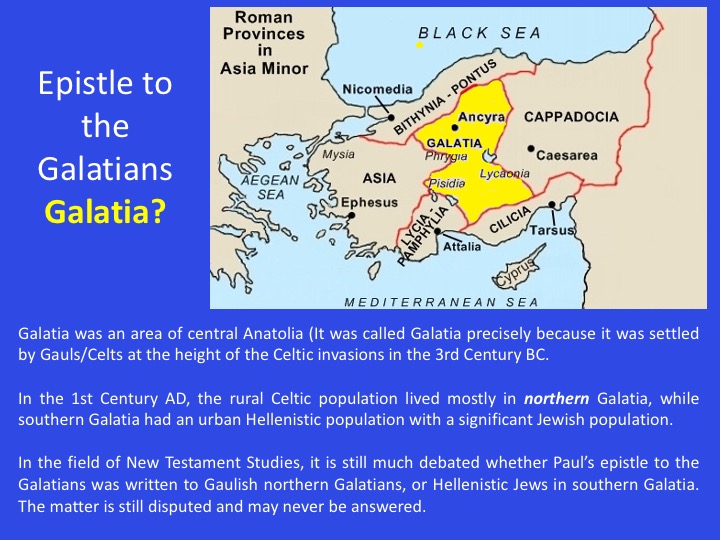

Galatians is the only one of Paul’s seven letters to be addressed to a group of communities rather than to a particular community or individual; it is sent to the “churches of Galatia.” Galatia was a region in central Asia Minor that contained several cities.

Epistle to the Galatians

Galatia?

Galatia was an area of central Anatolia (modern Turkey). It was called Galatia precisely because it was settled by Gauls/Celts at the height of the Celtic invasions in the 3rd Century BC.

However, In the 1st Century AD, the rural Celtic population lived mostly in northern Galatia, while southern Galatia had an urban Hellenistic population with a significant Jewish population.

In the field of New Testament Studies, it is still much debated whether Paul’s epistle to the Galatians was written to Gaulish northern Galatians, or Hellenistic Jews in southern Galatia.

The matter is still disputed and may never be answered.

Galatians (2)

These communities had become deeply conflicted since Paul was there. Paul himself was under attack; some were accusing him of having falsified the gospel.

Paul was very angry. He accuses the Galatian communities of “deserting” and “turning to a different gospel,” because of those who “pervert the gospel of Christ” (1.6–7). He pronounces a double curse on anyone who advocates a gospel other than the one they received from him (1.8–9). He calls them “foolish” and “bewitched” (3.1). He wishes that those who were troubling them “would castrate themselves” (5.12).

Galatians: it is the only one of Paul’s letters that does not include a thanksgiving after the greeting and blessing at the beginning. Clearly Paul was not feeling thankful for what was going on in his communities in Galatia. He was alarmed, furious, adamant. What was at stake was vitally and crucially important.

So what was at stake?

Galatians (3)

Requiring circumcision and observance of Jewish law would perpetuate the division between Jew and Gentile and thus destroy the unity of life “in Christ.” As perhaps the best-known text in Galatians puts it: In Christ Jesus, you are all children of God through faith. As many of you as were baptized into Christ have clothed yourselves with Christ. There is no longer Jew or Greek [Gentile], there is no longer slave or free, there is no longer male and female; for all of you are one in Christ Jesus. (3.26–28)

Paul is claiming the actual elimination of these distinctions within all Christian communities. He concludes in the very next verse” (3:29)

“And if you belong to Christ, then you are Abraham’s offspring” and “heirs” (3.29). Gentiles become children of Abraham not through circumcision, but by becoming “in Christ.”

1st Corinthians

is the second longest of Paul’s letters. Only Romans is longer, and thus this letter comes right after Romans in the canonical New Testament. But in this chronological New Testament, it comes after 1 Thessalonians and Galatians.

According to Acts, Paul created a Christ-community in Corinth in southern Greece around the year 50. Corinth was a major city, seaport, and capital of the Roman province of Achaia, which included Athens.

Though there was a Jewish synagogue there, the city was almost completely Gentile, cosmopolitan, and multi-ethnic. According to Acts, Paul spent eighteen months in Corinth on his first visit, probably from about 50 through 51. When he wrote this letter a few years later, he was in Ephesus in Asia Minor, just over two hundred miles across the Aegean from Corinth. It was not his first letter to the community in Corinth. He refers to a previous letter (5.9) and to a letter he has received from them (7.1).

1st Corinthians (2)

Paul has been away from it for a few years—probably at least two. Now he has learned that divisions and conflicts have developed within the community. But the “mood” of conflict is not nearly as intense as in Galatians or, as we will see, in 2 Corinthians.

Paul mentions there were divisions within the community between “the rich” and “the rest” particularly at meals, where the wealthier ones, who did not have to work, arrived early for the Lord’s supper and ate all the best food and wine

For when the time comes to eat, each of you goes ahead with your own supper, and one goes hungry and another becomes drunk. What! Do you not have homes to eat and drink in? Or do you show contempt for the church of God and humiliate those who have nothing? What should I say to you? Should I commend you? In this matter I do not commend you! (11.21–22)

Philemon

In our church Bible this is the last of the letters attributed to Paul, because it is the shortest.

It is written to a person rather than a community. And it is about two people, Philemon and Onesimus.

Onesimus was Philemon’s slave who had fled from him for reasons we do not know. To be a runaway slave was a very serious matter in that world.

Onesimus went to Paul in prison, presumably because he knew Philemon admired Paul, and he wanted Paul to intercede on his behalf. While visiting Paul he became a convert – a Christ follower.

Now Paul has sent Onesimus back to Philemon with this letter.

The letter is a masterpiece of persuasion. Pauls appeal to Philemon is “Take him back forever, no longer as a slave but a beloved brother. Welcome him as you would welcome me.

Philemon – the Teaching

The letter provides a case study of what life “in Christ” was to be like.

The issue was larger than resolving a conflict between Philemon and Onesimus.

It was whether slavery was acceptable within life “in Christ.” Philemon is a Christ-follower who has slaves. Onesimus has become a Christ-follower—he has become “in Christ.” Thus the issue is: May a Christian have a slave who has become a Christian?

A Christian master may not have a Christian slave.

Paul’s answer was an emphatic NO.

This letter is a concrete application of what Paul wrote about life in Christ in Galatians. If you have been “baptized into Christ” and “clothed yourselves with Christ,” there is no longer Jew or Gentile, slave or free, male or female, “for all of you are one in Christ Jesus” (3.27–28). Life “in Christ” abolishes the hierarchical relations of conventional culture. Its equality is not only spiritual, but also “in the flesh.”

We do not know how Philemon acted in response to Paul’s appeal.

Philippians

Philippians is the most consistently affectionate of Paul’s letters. Philippi was the capital of ancient Macedonia, in northern Greece. According to Acts 16, it was the first city in Europe in which Paul founded a Christ-community after leaving Asia Minor in the late 40s. It was written from a Roman prison and from his words seems uncertain about whether his imprisonment might end in his execution.

Yet It contains some of Paul’s most beautiful language about being joyful under all external conditions.

(4.11–13). “I have learned to be content with whatever I have. I know what it is to have little, and I know what it is to have plenty. In any and all circumstances I have learned the secret of being well-fed and of going hungry, of having plenty and of being in need. I can do all things through him [Christ] who strengthens me.“

Philippians (2)

(2.1–11). If then there is any encouragement in Christ, any consolation from love, any sharing in the Spirit, any compassion and sympathy, make my joy complete: be of the same mind, having the same love, being in full accord and of one mind. (italics added) It continues with “the mind,” “the love,” Christ-followers are to have: Let the same mind be in you that was in Christ Jesus, who, though he was in the form of God, did not regard equality with God as something to be exploited, but emptied himself, taking the form of a slave, being born in human likeness. And being found in human form, he humbled himself and became obedient to the point of death—even death on a cross. Therefore God also highly exalted him and gave him the name that is above every name, so that at the name of Jesus every knee should bend, in heaven and on earth and under the earth, and every tongue should confess that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father.

2nd Corinthians

Second Corinthians is not a single letter, but a combination of at least three letters from Paul to the Christ-community in Corinth.

The most common divisions are chapters 1–7, 8–9, and 10–13.

The community in Corinth preserved these letters and later combined them into one letter as 2 Corinthians.

Paul founded the community in Corinth around the year 50 and spent a year or two there.

Paul refers to a “painful visit” (2.1),

He mentions a letter to Corinth for which he partially apologizes (2.4; 7.8). Written in “distress and anguish” and with “many tears” (2.4), it may have been lost or it may be preserved in 2 Corinthians 10–13, angry chapters in which Paul vigorously defends himself and aggressively attacks those who have been maligning him.

2nd Corinthians (2)

Chapters 10-13

Paul attacks the teachers as “super-apostles” (11.5) and “false apostles, deceitful workers” (11.13). Then he superlatively compares himself to them, even as he apologizes for sounding like a boastful fool (11.21): “Are they Hebrews? So am I. Are they Israelites? So am I. Are they descendants of Abraham? So am I. Are they ministers of Christ? I am talking like a madman—I am a better one.” (11.22–23)

He describes an ecstatic religious experience that seems to have involved an out-of-body state of consciousness and traveling to another layer or level of reality—what Paul calls the “third heaven” and “Paradise” (12.2–4).

2nd Corinthians (3)

Chapters 1-7

Though parts of these chapters reflect conflict it also includes passages of great radiance, including some expositions of a number of Paul’s central affirmations.

In the metaphor of “unveiled faces” (3.12–18), Paul refers to “a veil” that lies over minds and continues with the good news that in Christ it is set aside: “When one turns to the Lord, the veil is removed. Now the Lord is the Spirit, and where the Spirit of the Lord is, there is freedom.” He continues: “And all of us, with unveiled faces, seeing the glory of the Lord as though reflected in a mirror, are being transformed into the same image from one degree of glory to another.” The gospel, the Christian message, is about is about a transformation of the mind.

Romans

Paul’s letter to the Christ-communities in Rome is distinctive in many ways. It is his longest letter. Only 1 Corinthians is a serious rival. It is the only letter he wrote to people he didn’t know; Paul had never been to Rome.

So, its main purpose was to introduce himself to a group of Christ-followers whom he planned to visit and from whom he hoped to receive support for a mission to Spain.

He did so by telling them about his “theology” in the broad sense of that word; that is, how he saw the significance of Jesus and its meaning for thinking about God, transformation, and the new life in Christ.

It is now viewed as the most theological of Paul’s letters, and the most important of his letters in the history of Christian theology.

as the most theological of Paul’s letters, and the most important of his letters in the history of Christian theology.

Its language of justification, grace, and faith, usually shortened to justification by faith, has been central to Protestant theology ever since.

Romans – Historical Context

The letter seemed to have another very important purpose. Explaining the the relationship between Jew and Gentile in the context of God’s covenant with Israel. The first verse of the body of the letter announces it. The gospel is the power of God for salvation “to everyone who has faith, to the Jew first and also to the Greek” (1.16)

21 ”But now God’s righteousness has been revealed apart from the Law, which is confirmed by the Law and the Prophets. 22 God’s righteousness comes through the faithfulness of Jesus Christ for all who have faith in him.

Then in chapters 9–11, the theme of God’s covenant with Israel, including Jews who had not become followers of Jesus, is explicit. Some scholars think these chapters are the climax and heart of the letter.

Romans – Historical Context

The letter seemed to have another very important purpose. Explaining the the relationship between Jew and Gentile in the context of God’s covenant with Israel. The first verse of the body of the letter announces it. The gospel is the power of God for salvation “to everyone who has faith, to the Jew first and also to the Greek” (1.16)

Then in chapters 9–11, the theme of God’s covenant with Israel, including Jews who had not become followers of Jesus, is explicit. Some scholars think these chapters are the climax and heart of the letter.

He agonizes about the nonresponse of many Jews to Jesus, emphasizes his own Jewish roots, and ponders what God’s promises to the Jews mean. The issue is no longer simply the relationship between Christian Jews and Christian Gentiles, but God’s relationship to Jews as a whole. His conclusion is that God’s promises to Israel are still valid: all of Israel will be saved.

Romans – Historical Context (2)

Why Was This So Important to Paul?

We do not know much about the Christ communities in Rome. We do not know exactly when they were founded, though we do know that there were Christ-communities in Rome by the mid-40s at the latest.

The Event

But, from Roman history we know that in the year 49, the emperor Claudius ordered the expulsion of Jews from Rome. For about 5 years the Christ followers were all Gentiles.

Then, in 54, Claudius’s edict was rescinded. How many Jews returned and how quickly they did so are unknown. And it was known that many of the Jews then began to return to Rome.

This historical context, accounts for Paul’s emphasis in this letter on the relationship between Jews and Gentiles.

Further Teachings

Chapters 5–8 include some of the most magnificent passages in Paul’s letters. They expand Paul’s theme to the new life “in Christ.”

5 Therefore, since we have been made righteous through his faithfulness, we have peace with God through our Lord Jesus Christ.

And in chapters 6-8 Paul treats:

The Christian life as dying and rising with Christ.

Life lived in the spirit.

The transformation of creation.

There is no separation from the love of God in Christ.

Ethical Instructions

As the letter nears its end, Paul turns to what is mostly ethical instruction. It begins with another emphatic “therefore,” after which Paul tells his readers what follows from what he had written thus far, the “so what.” This section begins with one of the most concise summations of Paul’s message:

(12:1-2) So, brothers and sisters, because of God’s mercies, I encourage you to present your bodies as a living sacrifice that is holy and pleasing to God. This is your appropriate priestly service. 2 Don’t be conformed to the patterns of this world, but be transformed by the renewing of your minds so that you can figure out what God’s will is—what is good and pleasing and mature.

Romans 15-16

Finally, at the end of Romans in chapter 16 there is a striking list of people that listed under a subtitle called Greetings to Roman Christians. I want to mention this list now because it will be used as an example next week when we talk about some later letters of Paul that bother many Christians. Of those Of those who are named, some are clearly Christian Jews and others Christian Gentiles. Even more striking is the number of women’s names. Of the twenty-eight individuals mentioned, ten are women. Of the eleven singled out for special praise, five are women. Paul uses the Greek verb for dedicated apostolic activity to refer to four of these women. One, Junia, is spoken of as “prominent among the apostles.” Leadership by women was a fact in early Christ-communities. Not only did Paul not challenge it; he obviously approved of it.

And on next week to the last week on the New Testament.