David and Nation Building - Session 1

Mike Ervin

As I was putting this together I realized that many of you had probably heard our previous class on Saul - the Tragic King, so I am going to VERY briefly review some pof that content from 1st Samuel. So this will review three weeks of classes in only 4 slides!! Reader Digest!

David and Nation Building

Introduction

In this first session, we turn to David, the successor to Israel’s first king, Saul. We were introduced to David in 1st Samuel, but David’s reign is recounted in 2nd Samuel.And what we find there is that David, more than anyone else, defined Israel’s identity as a nation. He won victories in war, brought unity to a divided people, and established a political dynasty that ruled for centuries. In many ways, belonging to the people of Israel meant identifying with the hope and promise that David represented.

David and Nation Building

Introduction - the Challenges

The challenge though, is that David became such a symbol of the nation that it can be difficult to get to know him as a person. To understand such figures with national significance, we need to look behind their iconic images. And we will try to do that in these studies.

David’s Triumphs

As you may recall from 1st Samuel, David was secretly anointed to be king while Saul, his predecessor, was still alive. Not long thereafter, Saul met his end in battle with the Philistines. Because there was no clear plan of succession, Saul’s death created a crisis of leadership that split the country in two. The northern part of the country thought that power should be transferred to Saul’s son. But people in the south thought power belonged to the most gifted leader, David, who was also a southerner.

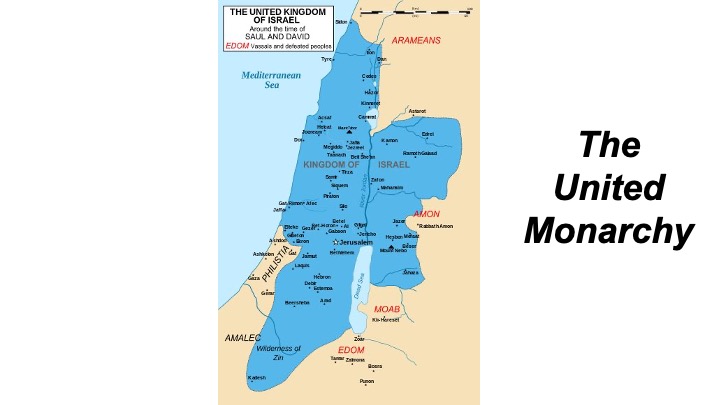

When the country split in half, the people of the north established their capital at a town called Mahanaim and referred to themselves as the people of Israel. At this point in the story, the name Israel refers specifically to the northern tribes. In contrast, the people of the south referred to themselves as the people of Judah. They located their capital at the city of Hebron, where David had his power base.

The peoples of Israel and Judah engaged in a civil war for some time; the tipping point came through palace intrigues and assassination in the north. Saul’s son lost the confidence of his key supporters, and they killed him. His death again created a power vacuum, convincing many in the north that the only real option was to give their support to David. Thus, the civil war ended when the people of the north came to David at Hebron and declared that they would recognize him as their king (2 Sam. 5) over a united country.

As we get into the story of David I want to emphasize what an important piece of literature this is. Robert Alter is a professor of Hebrew literature at Cal Tech Berkely and a renowned scholar of literature and of the ancient language of Hebrew. Let's look at a commentary he made on the story of David as literature.

David’s Challenge

David’s victory in the civil war created a new leadership challenge for him: It meant that he had the opportunity to lead the people into a different future, but the question was whether he would use that opportunity effectively or whether he would squander it.

Early on, David sought to unify the country, to move it beyond the old divisions created by civil war. A major step here was to create a new capital city, for which he chose Jerusalem. The city was located on the dividing line between north and south. David’s troops succeeded in capturing Jerusalem from the Jebusites, and it became the new political center for the country.

Because David also wanted Jerusalem to become the religious center for the nation, he decided to bring the Ark of the Covenant there. He staged a grand procession to bring the ark to his capital city and placed it in a tent.

On the one hand, we might read David’s success in giving Jerusalem both political and religious significance as an account of his devotion to God. After all, David offered prayers and sacrifices when he brought the ark to Jerusalem. We might discern in these actions the recognition that he, as king, is still subject to a higher authority, and that recognition would create an implicit limit in the use of political power. It would mean that David, as king, along with his people, were finally accountable to a God, whose authority was higher than theirs.

On the other hand, we might also read this as an account of David making use of religious rituals to serve his own political ends. He had already made Jerusalem into his new political capital. Thus, we might see the return of the ark as an effort to give religious support to his new central government. Instead of seeing David honoring the higher authority of God, we might see it as the opposite. We might interpret this as David’s attempt to use the authority of God to support his own royal agenda.

David as Founder of a Dynasty

At the beginning of 2 Samuel 7, David is comfortably settled into his house or palace in Jerusalem. He assumes that if he, as king, has a house, then God should have a house, too; specifically, he thinks that the Ark of the Covenant should have a permanent house or temple, rather than a tent. He relays this idea to a prophet named Nathan. The Ark of the Covenant was the great sign of God’s presence among the people, and David believed that its presence in the city would make Jerusalem the focus of religious life.

Nathan tells David that God is quite satisfied with the traditional practice of placing the Ark of the Covenant in a tent and sees no need to change that arrangement. Instead, God sees himself as the builder—the builder of a house or dynasty for David. God promises that David’s descendants will inherit his throne. And through that Davidic dynasty, God will establish a kingdom that will endure forever. Once God has built a house or dynasty for David, one of David’s sons can build a house or temple for God.

In that same passage, Nathan compares God’s relationship to the king to that of a father and his son. In ancient Israel, people believed that God adopted each king as his son, but that did not mean that the king was exempt from criticism. Nathan explains that just as an earthly father would discipline his son whenever the child did something wrong, God will discipline the king. Yet just as earthly father would remain committed to his son—even a disobedient son—God will remain committed to David and his heirs forever.

Instead, Nathan goes on to explain that God sees himself as the builder - the builder of a house or dynasty for David. God promises that David’s descendants will inherit his throne. And through that Davidic dynasty, God will establish a kingdom that will endure forever.

Once God has built a house or dynasty for David, one of David’s sons can build a house or temple for God.

As we continue reading 2 Samuel, we find that despite the promise of God’s support, David is deeply flawed. He is capable of infidelity and brutality and must come to terms with the consequences of his own personal failings.

In 2 Samuel 11, David is at home in his palace in Jerusalem while his army is fighting many miles away. One day, David catches a glimpse of a beautiful woman, Bathsheba, bathing in a house nearby. Her husband is away on active military duty. David has Bathsheba brought to his room, where he sleeps with her. Sometime later, Bathsheba lets David know that she is pregnant.

David thinks he can cover up the affair by bringing Bathsheba’s husband back from military duty for a short home visit. But the husband refuses to sleep with Bathsheba while all his men are camped in the field. Then, David sends Bathsheba’s husband on a suicide mission and takes Bathsheba as his own wife after her husband is killed.

The prophet Nathan is appalled by David’s machinations. Nathan had told David that God wants to build him a dynasty and that God will establish David’s kingdom forever. Nathan confronts David by telling a parable (2 Sam. 12), in which a rich man unjustly slaughters the lamb of a poor man.

Outraged at the injustice in the parable, David condemns what the rich man has done and declares that the rich man must repay the poor man four times the amount taken. Already, we can see the parable doing its work. Nathan did not have to tell David that what the rich man did was unjust.

The story moved David himself to see the injustice. This allows Nathan to turn David’s judgment against the rich man in the story into a judgment against David’s own actions.

To make sure that David does not miss the point, Nathan tells him that if it is wrong for a rich man to take a poor man’s lamb, then it is far worse for the king to seize another man’s wife. And it is unconscionable to have the man killed in order to cover up the affair. This audacious confrontation of the king works. David acknowledges his wrongdoing. That is perhaps the one admirable trait David displays in this whole sordid affair: He proves capable of taking ownership for what he has done.

Nathan forgives David, but forgiveness does not mean that David’s actions have no consequences. Nathan warns that David has set in motion a pattern of violence that will continue into the next generation. To be sure, David repents of what he has done, but he cannot control what his children will do. And the last part of 2 Samuel tells of the violent pattern that David has set in motion being followed by one of his sons, Absalom.