A Study of James - Lesson 1

Mike Ervin

A STUDY OF JAMES LESSON 1 Feb 14, 2021

Welcome back to virtual learning! It is good to see friendly faces – even if they are coming through the cameras of computer devices. And not panem et panem.

For the next two weeks we will examine a very interesting book in the New Testament. It is commonly called the Epistle (or letter) of JAMES, although most modern scholars no longer consider it an epistle. And we will be explaining why that is.

So – Why Study James?

One of the themes we have tried to carry forward in the Third Well class is that “serious” Christians might want to read all of the Bible. But it is quite clear and somewhat embarrassing that “average” Christians are woefully unaware of what is in many parts of the Bible, and many Christians don’t read James, or hear sermons about James. We will talk about that. So one reason we want to study James is that for many of us it will be the first time!

And you may ask why we are devoting 2 weeks of study to a book that in my desk bible is 3 and a half pages long. It is a good question – because we could just read the entire book out loud in one lesson and go home.

But we are not going to do that. Because as I said earlier James is a very interesting book, both historically during the development of the canon, and in the many discussions that came about as Christianity evolved. So we are going to be reviewing a lot of that background before then doing a dive into the text itself. And we will be discussing James as wisdom literature, the only NT book normally described as wisdom literature. So we explore what that means.

•So, what about those “average” Christians? Polling organizations routinely question self-identified Christians, and the results are quite embarrassing.

• One of the questions that has been repeated several times in these polls is simply: “Please name the four Gospels”.

•Only 52 % of the respondents get this right.

•George Gallup Jr. of the Gallup poll has been quoted as saying: “Our results show that Christians clearly revere their bibles, but they don’t read them.”

Canonization’s Rocky Road

OK - so we mentioned that the canonization of the New Testament was not exactly an easy process - it was filled with controversy for centuries.

Let’s begin with our new word of the day – ANTILEGOMENA. In roughly 325 C.E. Eusebius of Caesarea, an early Christian historian, and later Christian Bishop, was also a scholar of the development of the biblical canon and in writing about the canon in his book Church History invented this word. It was his name for those Christian scriptures that were “in dispute”. JAMES was one of those. But certainly not the only one.

These disputed writings, were widely read in the early church and included James, Jude, 2nd Peter, 2nd And 3rd John, The Book Of Revelation, The Gospel Of The Hebrews, The Epistle Of The Hebrews, The Apocalypse Of Peter, The Acts Of Paul, The Shepherd Of Hermas, The Epistle Of Barnabas, And The Didache. The term "disputed" should therefore not be misunderstood to mean "false" or "heretical". There was disagreement in the Early Church on whether or not the respective texts deserved canonical status.

And in 367 C. E. Athanasius of Alexandria, in a letter to all of the bishops indicated the 27 books that he felt deserved to be in the canon. Athanasius gave credit in his writings to the work of Eusebius in guiding his recommendations. Those 27 are today’s 27 books of our Protestant New Testament.

The Letter of JAMES was accepted as scripture by the church in Alexandria in the third century of the Common Era, by the Western church in the fourth century, and by the Syrian church in the fifth century. But as we have learned from our other studies the canonization of the New Testament was by no means a conflict free event. And the rocky road was not over.

Even though it remained in the NT canon of all churches, the conflict reappeared 12 centuries later at the time of the Reformation when Martin Luther questioned the book of James’ status because it appeared to contradict Paul’s teaching on justification by faith, or at least Luther’s interpretation of Paul’s teaching which Luther held to be of central importance to Christianity. More recent interpreters have come to appreciate James’s distinctive theological perspective and his impassioned practical concern about how we should live. In many ways it is written as a treatise on Wisdom. And we will also talk about James as wisdom literature as we proceed in this study.

The Luther Canon

Before leaving Luther, we should briefly review Luther’s other concerns about the NT canon. When Luther did his great translation of the bible into German, he considered Hebrews, James, Jude, and the Revelation to be "disputed books". He included them in his translation but placed them separately at the end in his New Testament published in 1522. This group of books begins with the book of Hebrews, and in its preface Luther states, "Up to this point we have had to do with the true and certain chief books of the New Testament. The four which follow have from ancient times had a different reputation." Luther still considered Hebrews, James, Jude, and the Revelation to be "disputed books".

We mentioned earlier many of us seldom hear sermons on books like James or even hear scripture readings from James during worship services. One way of understanding that is to review the concept of the Revised Common Lectionary.

The Revised Common Lectionary is a lectionary of readings from the Bible for use in Christian worship, based on the liturgical year. You have undoubtedly experienced the regular reading of scripture from the pulpit each Sunday – scripture from our bible. And often we will get a sermon linked to one of those readings.

Readings are prescribed for each Sunday: a passage typically from the Old Testament, or the Acts of the Apostles; a passage from one of the Psalms; another from either the Epistles or the Book of Revelation; and finally a passage from one of the four Gospels.

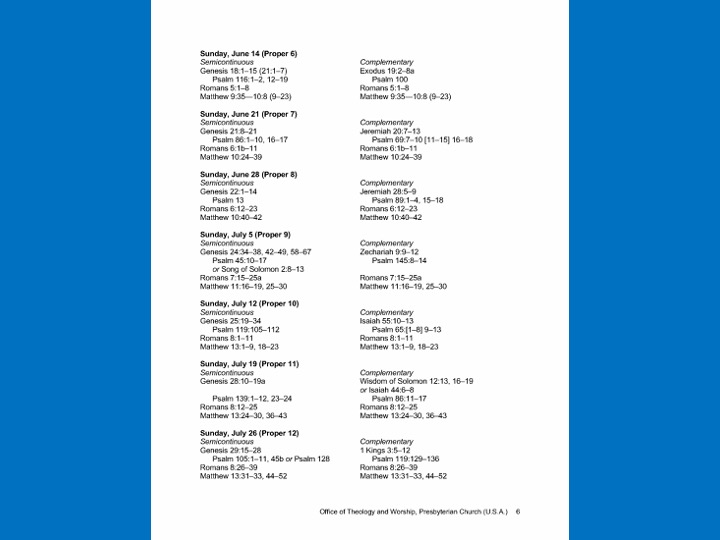

In the next 3 slides I will briefly show you three pages from the 2020 Revised Common Lectionary for Presbyterian Church USA (that's us). The 2020 Lectionary is actually about 9 pages long, but I just wanted to give you a feel for what it looks like.

Now, in reviewing this Revised Common Lectionary I want to be sure you understand i am not critical of having a Common Lectionary. In fact I think it is a great concept. The idea is that over a three year period of hearing scripture from the pulpit, often followed by sermons that are developed off of those readings, the worshipers attending those services will get exposed to the entire Bible, and not only hear all parts of the bible, but avoid never hearing some parts because a particular church only sticks to the scriptures they prefer.

That is the concept. But in practice that is a very difficult goal to achieve simply because the bible, all 66 writings, is so large it is simply impossible to cover everything in three years,

For example, if I showed you all 9 pages of the 2020 lectionary, instead of only three pages, you would still find no readings from James. And as a result probably no sermons from James that year..

Other criticisms from scholars - the lectionary seriously short changes the Hebrew bible (a.k.a the Old Testament). And it does, in fact it short changes almost everything outside of the four Gospels. The Hebrew bible readings seem to be primarily from the Psalms, and from Isaiah.

I point all of this out to support my initial contention that one of the reasons most modern Christians do not "know" their bibles much is that unless they do independent bible study outside of worship services (Sunday school or bible studies) they cannot possibly be that conversant about the bible.

JAMES as “Wisdom Literature”

And so, I would now suggest that we do study James, and furthermore study it in a new way, namely to examine James through the lens of wisdom literature. So what does that mean?

Wisdom literature is a genre of literature common in the ancient Near East. It consists of statements by sages and the wise that offer teachings about divinity and virtue.

Many religious traditions include wisdom literature as one of their genres. That definitely includes the Judaeo/Christian traditions. Within the Hebrew Bible there is an identified group of Wisdom writings with which we are familiar.

In early Christianity James was usually lumped into the Epistles in the New Testament, in that it’s beginning seems to be in classic Greek letter form, but that conclusion has changed over time. Modern scholarship has turned to a conclusion that James is much more a book of ethical instructions. One scholar has noted that there are 8 verses in James that mimic eight verses in Leviticus which involved ethical instructions to Israel.

The vigorous and fresh writing style of James is also similar to Old Testament wisdom passages. James generally uses short and vivid sentences. He is fond of making comparisons to nature-waves, sun, flowers, planets, and animals-to give his teaching concrete expression. He asks his readers short, penetrating questions to cause them to reflect. He speaks in proverbs. Sometimes he uses the form of the diatribe, a scathing denunciation of immoral behavior. All these literary devices are common in moral and ethical literature.

So when we get into the text of James we will look for these patterns.

The Hebrew bible texts that are usually described as wisdom literature are Job, Psalms, Proverbs, Song of Songs and Ecclesiastes.

So what is wisdom literature. Not easy to define but the word wisdom refers less to “factual” knowledge and more to skills in living. Particularly biblical literature deals with knowing how to live. Much of it is also strong on ethics.

In the Christian New Testament the writings that are most often seen as wisdom writings include Jesus’s Sermon on the Mount in Matthew, in some specific instructions from the Epistles, and particularly in the book of James.

In early

Christianity James was usually lumped into the Epistles in the New Testament,

in that it’s beginning seems to be in classic Greek letter form, but that

conclusion has changed over time. Modern scholarship has turned to a conclusion

that James is much more a book of ethical instructions. One scholar has noted

that there are 8 verses in James that mimic eight verses in Chapter 19 in

Leviticus which involved ethical instructions to Israel.

The vigorous and fresh writing style of James is also like Old Testament wisdom passages. James generally uses short and vivid sentences. He is fond of making comparisons to nature - waves, sun, flowers, planets, and animals - to give his teaching concrete expression. He asks his readers short, penetrating questions to cause them to reflect. He speaks in proverbs. Sometimes he uses the form of the diatribe, a scathing denunciation of immoral behavior. All these literary devices are common in moral and ethical literature.

So, as we proceed to read James in our next lesson (Lesson II), we are going to try to read it through the lens of wisdom literature, not as an epistle, which it was earlier assumed to be.

Author, Date, Place and Addressees.

And so, in our last slide today before we tackle James next week, let's review the typical questions that arise in studying any of the New Testament writings. Who wrote it, when, from where, and to whom was it addressed?

And as usual, we do not have definitive answers to any of those questions. So let's begin here to read James chapter 1 verse 1.

James 1:1 “From James, a slave of God and of the Lord Jesus Christ. To the twelve tribes who are scattered outside the land of Israel. Greetings!”

THE “JAMES” of the opening address has traditionally been identified as James the brother of Jesus (Gal 1.19), who became the leader of the church in Jerusalem (Acts 15.13; 21.18) and who was martyred before the outbreak of the Jewish war of 66–70 CE (see Josephus, Antiquities 20.200).

But there is no indication anywhere in the book of James that the James of the first verse is the brother of Jesus. It raises the question of why would this writer omit that seemingly important fact. Because James was a quite common name at that time.

And the author’s proficiency with Greek, has suggested to some that the brother of Jesus probably did not write this text. Whoever wrote James was clearly highly educated in the Greek language and Greek rhetoric, and to scholars this seems unlikely for a peasant from the Galilee, where the predominant language was Aramaic.

The memory of James was widely revered in the early church, and his name may have been used by another writer to preserve his legacy. At any rate, the letter’s lack of references to developed ecclesiastical structures, its practical OT morality, and its echoes of the teachings of Jesus, probably drawn from oral tradition, are all consistent with an early, Palestinian origin. Its critical interaction with what appears to be a misuse of Paul’s teachings (2.14–16) shows that different interpretations of Christianity were already current.

So, again, scholars are widely divided on whether this James was the brother of Jesus, and there is no firm consensus on who the author was. Equally unknown for sure was the date of the writing, and the place. The addresses are unclear because most scholars no longer agree that this was an epistle to a certain group, but instead was ethical and moral instructions to a nation.

And in Lesson II we will finally examining this writing, with a particular emphasis on James as Wisdom literature. See you then.