Story of the Bible Lesson 5

Formation of Jewish and Christian Canons

Story of the Bible Lesson 5

The Formation of Jewish and Christian Canons

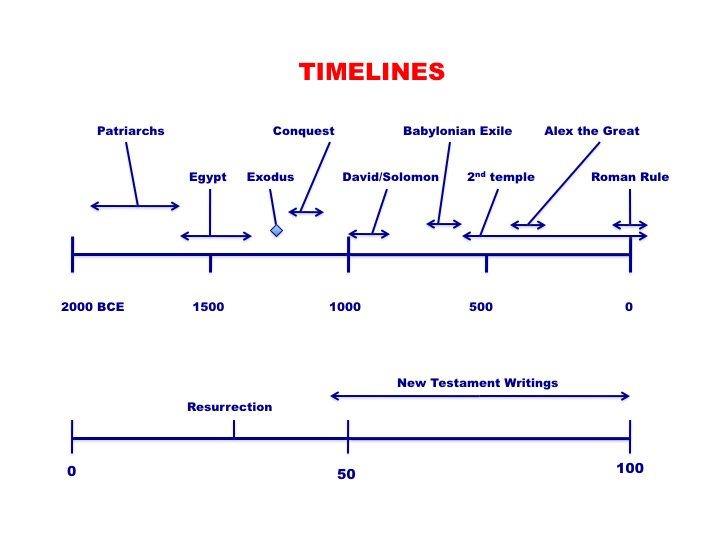

Here is the somewhat complex picture I have been presenting in the first part of our series - trying to show that the Jewish scriptures went through a 2000 year development, much of it being oral at first, but later written down during two periods - during the kingdoms of David and Solomon. And by contrast all of the formative writings of Christianity were written in a brief 70 year span.

But for both traditions there was no agreement regarding a canon in the early part of the 1st century. Judaism was broken up into factitious groups that not only did not get along with each other but each had its own views of what scripture was and how to interpret it. We will review that again shortly.

In Christianity there was no agreement simply because there had not been enough time for the nascent religion to even define itself, much less define a canon.

Overall Scope

Although Christians interacted with Jewish Scriptures in their earliest writings, the canon formation of the Jewish and Christian Bibles occurred over the same time period of the first centuries of the Common Era.

This presentation traces what we can know of the process within each tradition.

In Judaism, formation of the canon was largely a matter

of confirming earlier usage, especially that found among the Pharisaic party.

In Christianity, canon formation was more contentious. An early period of

exchange and collection of writings was interrupted in the 2nd century by

controversies that argued, on one side, for the truncation of authoritative

writings and, on the other side, for their expansion. The official Christian

Bible was not fully ratified until the end of the 4th century, but the basic

conflict was resolved in principle by the end of the 2nd century.

Canons – What and Why?

Canon (Greek word) – rule or measure.

Operational Definition

The writings that are to be read out loud to the assembly for worship and as guides to orthodoxy and orthopraxy.

Important to Understand - Most religions do not have a formal canon!

For Jews and Christians

1. A strong sense of communal identity .

2. A sense that a common collection of scripture will help guide the community.

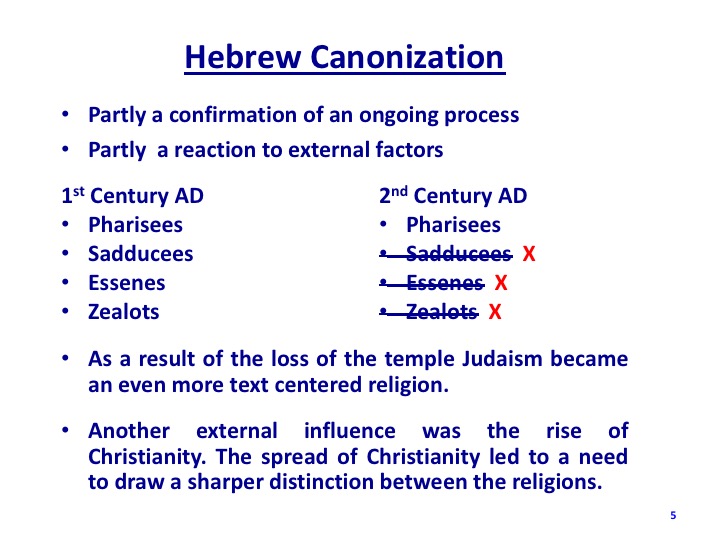

The canonization of the Hebrew bible eventually resulted in a confirmation of an ongoing process but it was a process that was also partly forced by external factors. As you may recall from our earlier classes the numerous sects within Judaism had major differences as to what was acceptable religious text in the early part of the 1st century of the common era.

As examples both the Sadducees and the Samaritans of the old northern Kingdom of Israel strongly believed that the 5 books of the Torah were the only acceptable sacred text. From what we learned in the 20th century discovery of the Deal Sea scrolls from the community of Qumran the Essenes also studied the Torah, but also the Prophets (not so much the Writings) and also wrote further interpretations of the Torah in light of their more recent experiences. The Zealots we know little about because we have recovered little of their literature.

The Pharisees were much more inclusive - they read all three parts of the TaNaK - Torah, Prophets, and Writings and considered all of them as authoritative. In addition the Pharisees had carried forward the concept that Moses had also passed along an "Oral Torah" - which they kept alive. The Sadducees totally rejected the notion of an oral Torah. More about how that was eventually written down later.

So the first "external factor" driving canonization of the Hebrew Bible was what happened in the year 70 A. D. The Roman army brutally attacked the area around Jerusalem, leveled the city walls, leveled the temple, and killed everyone in sight. Many Jews were killed, and quite a few fled for their lives.

But if you looked at Judaism shortly after that their was only one significant Jewish sect remaining - the Pharisees. Although this is probably an oversimplification, the arguments over "what is our scripture?" were ended. After the first century their is little historical evidence of Sadducees, Essenes, or Zealots. The only remaining sects are the Pharisees, many of which were spread across the Diaspora, and the newly emerging party of "Messianic Judaism" - soon to be called Christians.

The Sadducees, whose religious identity was strongly linked to the temple and the sacrificial method of worship simply never reappeared.

Judaism became even more a text-centered religion. Pharisaic Judaism became known as rabbinic Judaism with the teachers and interpreters of the texts leading the way.

A second external factor was the rapid rise of Christianity. The Christians got into rancorous arguments during the second century about what books were acceptable (and unacceptable) in both the Septuagint and the emerging New Testament. As the Christians became more critical about what came to be called the Apocrypha of the Septuagint, many Jews were asking the same questions and a clamor arose about further defining what was acceptable in Judaism. This drove conversations regarding canonization.

Hebrew Canonization

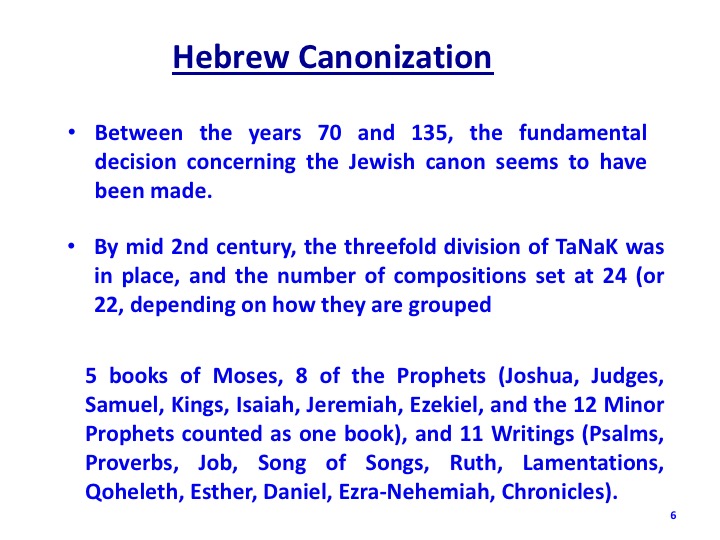

Between the years 70 and 135, the fundamental decision concerning the

Jewish canon seems to have been made.

By mid 2nd century, the threefold division of TaNaK was in place, and the number of compositions set at 24 (or 22), depending on how they are grouped.

5 books of Moses, 8 of the Prophets (Joshua, Judges, Samuel, Kings,

Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and the 12 Minor Prophets counted as one book), and

11 Writings (Psalms, Proverbs, Job, Song of Songs, Ruth, Lamentations, Qoheleth, Esther, Daniel, Ezra-Nehemiah, Chronicles).

Christian Canon

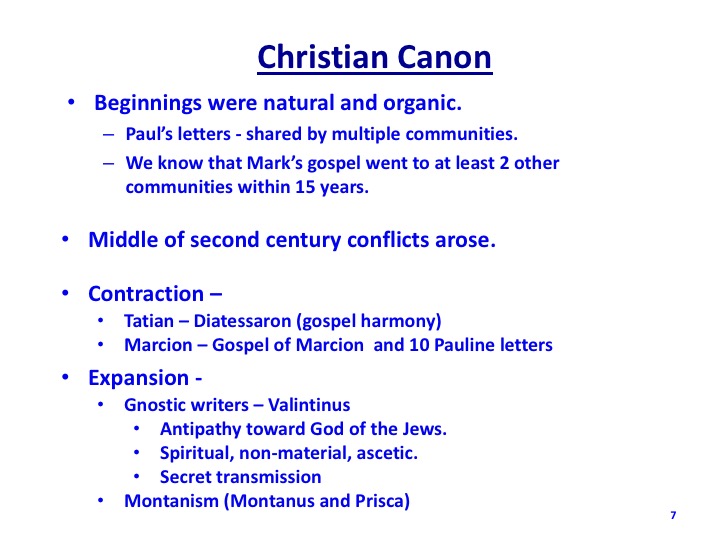

The Christian's canon beginnings were natural and organic. As Paul's letters were starting to be circulated we know they were being shared by several communities. Letters form other apostles gradually became better known.

We also know from our previous learnings regarding the synoptic problem that Mark’s gospel was probably written first in about the year 70 but went to at least 2 other communities (that of Matthew and of Luke) within 15 years.

And it is generally thought that both Matthew and Luke used the written version of Mark's gospel to create the basic story flow of the ministry of Jesus while relying on a second source ("Q") that was a listing of the sayings of Jesus. John's gospel was probably later and was distinct from the three synoptic gospels in many ways.

But by the middle of the 2nd century conflicts arose. These could be broken up into two camps - a camp of contraction, arguing for simplifying the canon - and a camp of expansion - wanting to add many other books.

Contraction

Two notable examples. First - Taitian and the Diatessaron

The Diatessaron (c. 160–175) is the most prominent early gospel harmony, and was created by Tatian, an early Christian Assyrian apologist and ascetic. Tatian was a pupil of 2nd-century Christian convert, apologist, and philosopher Justin Martyr. Tatian sought to combine all the textual material he found in the four gospels—Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John—into a single coherent narrative of Jesus's life and death.

The Diatessaron became adopted as the standard lectionary text of the gospels in some Syriac-speaking churches from the late 2nd to the 5th century, when it gave way to the four separate Gospels. At the same time, in the churches of the Latin west, the Diatessaron circulated as a supplement to the four gospels, especially in the Latin translation.

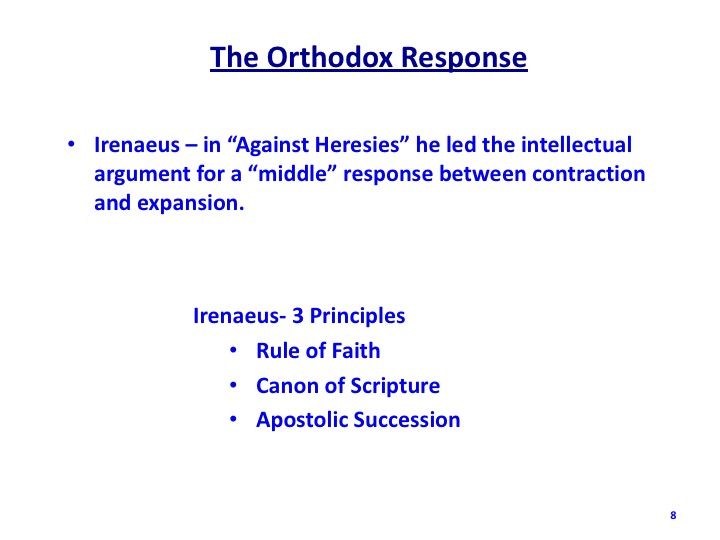

But several of the church fathers, especially Irenaus, forcefully argued that gospel harmonies were a mistake because the different interpretations of the teachings of Jesus from different communities were critical in understanding Jesus and his message.

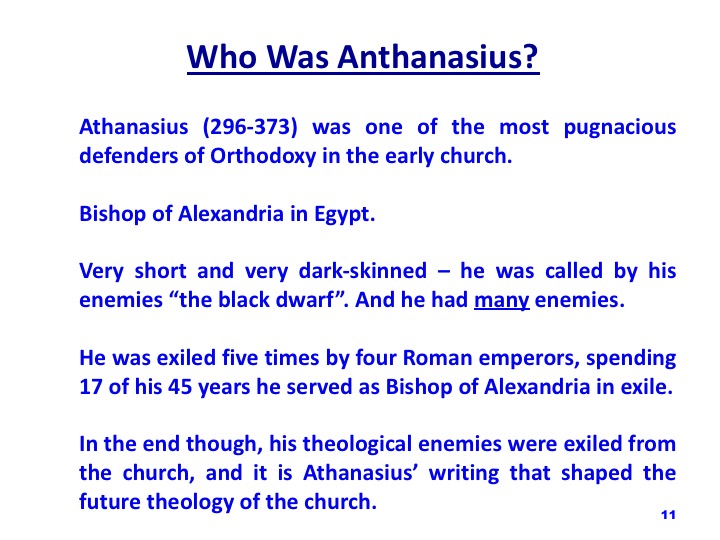

Who Was Anthanasius?

Athanasius (296-373) was one of the most pugnacious defenders of Orthodoxy in the early church. He was the bishop of Alexandria in Egypt. Very short and very dark-skinned – he was called by his enemies “the black dwarf”. And he had many enemies. After Constantine made Christianity a legal religion of the Empire he became very concerned that Christianity was in a major conflict between the "orthodox" camp and the "Arian" camp. Arias was a Bishop who questioned the newly emerging Doctrine of the Trinity and the notion of Jesus having two natures - fully human and fully divine. The Council of Nicaea was convened by Constantine to agree to only one form of Christianity. Athanasius represented the orthodox position and debated Arias in a furious interchange that finally resulted in a vote of the Bishops in favor of the newly drafted Nicene Creed. Arias and many of his followers refused to sign off on the creed and they were then banished into exile by the Emperor.

Athanasius victory was relatively short lived when the next Emperor (an Arian supporter) released Arias and exiled Athanasius. In further proof that Athanasius had many enemies he was exiled s total of five times by four Roman emperors, spending 17 of his 45 years he served as Bishop of Alexandria in exile.

In the end though, his theological enemies were exiled from the church,

and it is Athanasius’ writing that shaped the future theology of the church.

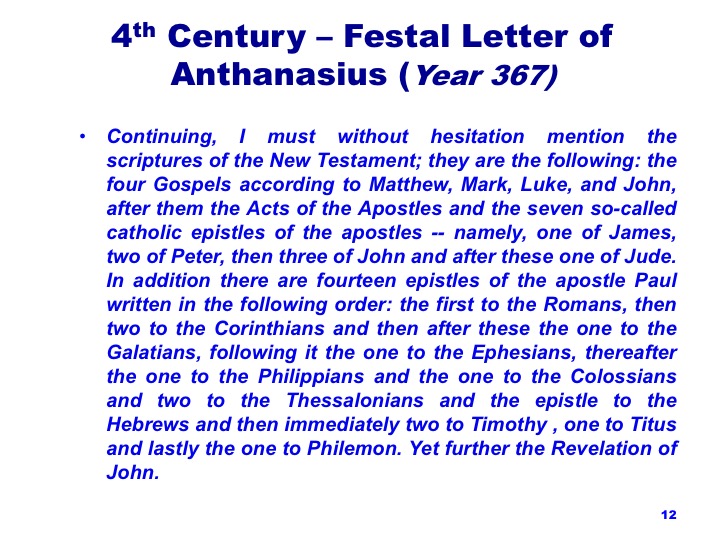

4th Century – Festal Letter of Athanasius (Year 367)

It had become a tradition in the emerging church that the Bishop of Alexandria each year wrote a Festal letter to all of the Bishops declaring the dates for that year of things like the beginning day of Lent and the Sunday of easter. Athanasius wrote the Festal letter in 367 and took advantage of its wide circulation to also weigh in on what he considered the canon to be.

Here was his statement:

Continuing, I must without hesitation mention the scriptures of the New Testament; they are the following: the four Gospels according to Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, after them the Acts of the Apostles and the seven so-called catholic epistles of the apostles -- namely, one of James, two of Peter, then three of John and after these one of Jude. In addition there are fourteen epistles of the apostle Paul written in the following order: the first to the Romans, then two to the Corinthians and then after these the one to the Galatians, following it the one to the Ephesians, thereafter the one to the Philippians and the one to the Colossians and two to the Thessalonians and the epistle to the Hebrews and then immediately two to Timothy , one to Titus and lastly the one to Philemon. Yet further the Revelation of John.

If you were doing your arithmetic in reading this you will see that he listed the 27 books that now make up today's Protestant bible. but then ho goes on:

But for the sake of greater accuracy I add, being constrained to write, that there are also other books besides these, which have not indeed been put in the canon, but have been appointed by the Fathers as reading-matter for those who have just come forward and which to be instructed in the doctrine of piety: the Wisdom of Solomon, the Wisdom of Sirach, Esther, Judith, Tobias, the so-called Teaching [Didache] of the Apostles, and the Shepherd. And although, beloved, the former are in the canon and the latter serve as reading matter, yet mention is nowhere made of the apocrypha; rather they are a fabrication of the heretics, who write them down when it pleases them and generously assign to them an early date of composition in order that they may be able to draw upon them as supposedly ancient writings and have in them occasion to deceive the guileless.

As you can see he further identified some "pretty good" books which can be good "reading material" for Christians. But is careful to say they are not in the canon. He further identified "the apocrypha" as being heretical. What can be confusing here is that there is no one agreed to listing of the apocrypha, and different strands of Christianity list slightly different apocrypha. As an example here is one listing of apocrypha:

Apocrypha

Tobit

Judith

Wisdom of Solomon

Sirach

Baruch

Susanna and the Elders

Bel and the Dragon

Esther Additions

1 Maccabees

2 Maccabees

3 Maccabees

1 Esdras

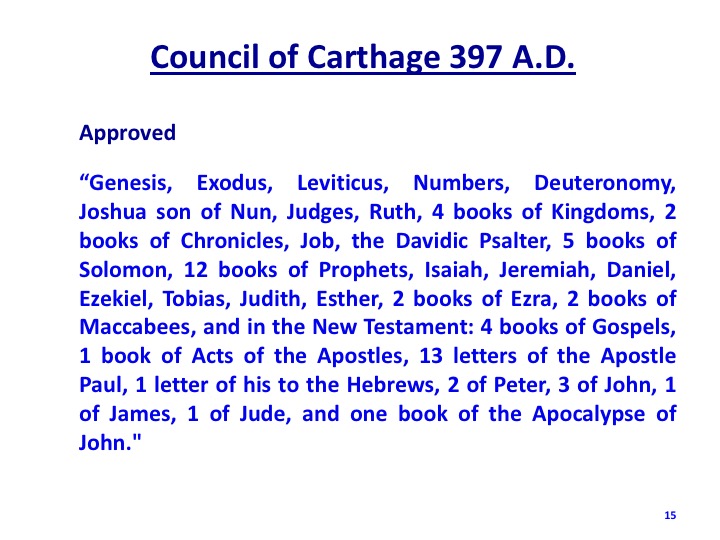

Council of Carthage 397 A.D.

The first "official" canon came out of the Council of Carthage in the year 397. This was the canon of the old and new testaments for Christianity. It was presented without much fanfare in the reports from the Council:

Approved

“Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy, Joshua son of Nun, Judges, Ruth, 4 books of Kingdoms, 2 books of Chronicles, Job, the Davidic Psalter, 5 books of Solomon, 12 books of Prophets, Isaiah, Jeremiah, Daniel, Ezekiel, Tobias, Judith, Esther, 2 books of Ezra, 2 books of Maccabees, and in the New Testament: 4 books of Gospels, 1 book of Acts of the Apostles, 13 letters of the Apostle Paul, 1 letter of his to the Hebrews, 2 of Peter, 3 of John, 1 of James, 1 of Jude, and one book of the Apocalypse of John."

For many years this was thus the canon of the western Catholic church.

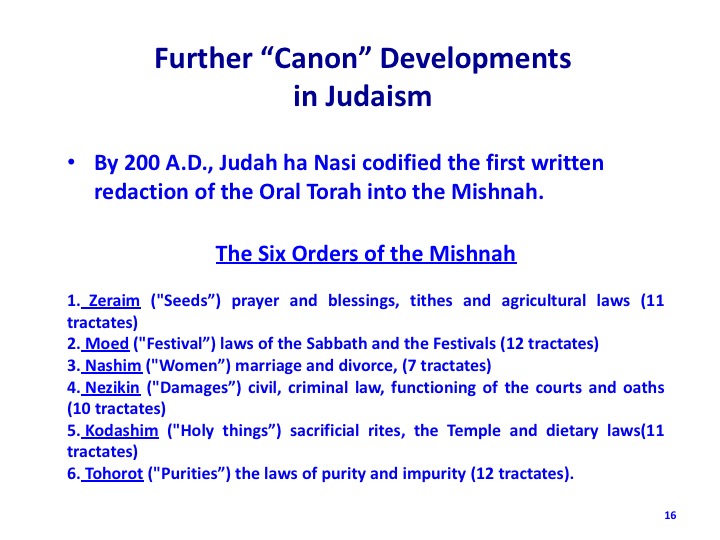

Further “Canon” Developments in Judaism

A Written Redaction of the Oral Torah into the Mishnah.

It was redacted c. 200 AD by Judah ha Nasi when, according to the Talmud, the persecution of the Jews and the passage of time raised the possibility that the details of the oral traditions dating from Pharisaic times (536 BC – 70 AD) would be forgotten. It is thus named for being both the one written authority (codex) secondary (only) to the Tanakh as a basis for the passing of judgment, a source and a tool for creating laws, and the first of many books to complement the Bible in a certain aspect. The Mishnah is also called Shas (an acronym for Shisha Sedarim - the "six orders"), in reference to its six main divisions. Rabbinic commentaries on the Mishnah over the next three centuries were redacted as the Gemara, which, coupled with the Mishnah, comprise the Talmud.

Further “Canon” Developments in Judaism

Between 200 and 600 A.D., further rabbinic debate on the Mishnah in light of TaNaK led to the development of two compilations that guided Jewish practice through the centuries: the Babylonian Talmud and the Talmud of the Land of Israel.