History of Christianity Class 6

Christianity and Imperial Politics

Mike Ervin

History of Christianity

Christianity and Imperial Politics - Class 6

In the series of classes to date, we saw how Christianity, beginning as an inauspicious sect of Judaism, grew—despite hostility and persecution— into a significant player in the larger world, with strong internal organization, an empire-wide system of communication, and an increasing confidence in both its moral and intellectual superiority. We now take a major turn in the course, just as Christianity took a major turn in the 4th century. From this point forward, it will be difficult to disentangle Christianity as a religious phenomenon from its role in the political order. As we now turn to examining how the persecuted Christian cult became the established religion of the Roman Empire.

The Transition of Christianity

The transition of Christianity from a persecuted cult to an established religion is represented by the emperor under whom the last great persecution was carried out, Diocletian (284–305), and the emperor under whom toleration and much more occurred, Constantine I (306–337). But history is not merely a matter of great men, however important; beneath their actions, powerful social forces were at work.

The Roman Empire’s transition from pagan to Christian was more gradual, and more complex, than is sometimes thought. We have seen how Christianity grew in numbers, organization, and intellectual self-confidence in the preceding centuries. The consequences of Constantine’s decision to establish Christianity as the imperial religion were, however, for both empire and church, undoubtedly decisive. Nothing was ever again the same for either.

The empire, which had already left behind its republican roots with the first Caesars and become increasingly autocratic, found itself patron of a religion with subversion in its genes. It is not clear whether the emperors had any idea how resistant to imperial rule Christianity could be.

The church, which had flourished as a religious movement during centuries of oppression and persecution—flourished, moreover, as a religion committed to peace, nonviolence, and other countercultural values—found itself the pillar and support of the world’s mightiest military and political power. It never did completely resolve the internal tensions its new status created.

History of Christianity

Diocletian’s Reforms

• It is important to undertand tha Diocletian was as important as Constantine for the shaping of imperial Christianity because he gave a new shape to imperial politics. It is against the backdrop of Diocletian’s reforms, as well as his persecution, that we can best understand the significance of Constantine’s initiative.

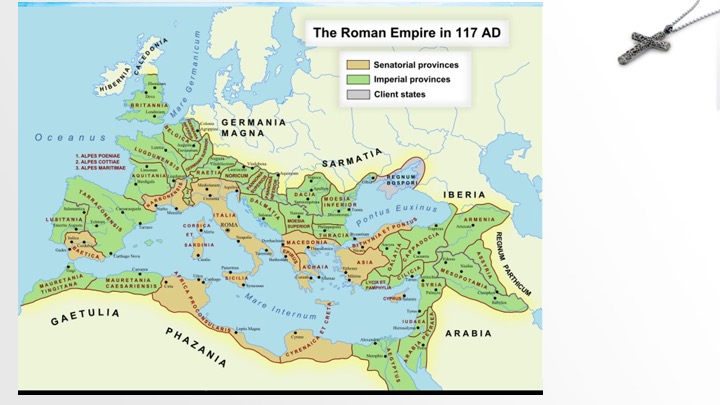

• After a “golden age” in the 2nd century—the reigns of Trajan and Hadrian in particular seemed a high watermark for enlightened imperial rule—the empire suffered severe internal and external threats throughout the 3rd century, especially from 235 to 285, when it was in almost a condition of anarchy.

o The Sassanid Empire (224–651) brought Persian/Parthian power to a threatening position in the east, reaching as far west as Antioch in the 250s.

Germanic peoples on the Danube and the Rhine had begun the “invasions”—more properly, migration - that exercised increasing pressure on the empire in the west.

The empire was in a bad financial state. Rome had always depended on conquest for the acquisition of new wealth; with the face of victory turning away from the empire, such easy wealth was less available. The economic situation was made worse by famine, plague, and monetary inflation.

From within, there was political unrest, with imperial pretenders contending for power. Since the time of Augustus, the usual way to become an emperor was through acclamation by Roman troops (often after an assassination) ; the temptation to military leaders with ambition was constant.

Diocletian was an exceptionally intelligent and strong leader who literally saved the Roman Empire by centralizing authority and instituting rigid control, especially of prices, throughout the empire. He established a hierarchical administrative structure with a complex bureaucracy, including a division of responsibility among an Augustus and a Caesar in both the east and west, so that the empire was administered by a tetrarchy, together with a plan for succession.

He increased the size of military forces, making increased use of mercenaries for the defense of the empire, a practice that broke with the tradition of a citizen army but secured the borders and the Roman peace once more, at least temporarily.

He established rigid price controls and increased taxes throughout the empire. “Police control” of the populace— formerly a fear of those who were “enemies of the Roman order,” such as philosophers and Christians—became a factor in the lives of others.

With all this came the further exaltation of the supreme leader; the cult of the emperor and the imperial family was the essential religious glue of society.

Through his reforms, Diocletian laid the groundwork for the late Roman Empire that, in all but one important way, would continue as the Byzantine Empire until its final collapse in 1453.

History of Christianity

The Persecution under Diocletian

• The last great persecution of Christianity was also the most vicious, and it was entirely consistent with Diocletian’s policy, for he sought by persecution to make traditional Greco-Roman religion secure and uniform throughout the empire. Christianity had become too large a counterforce to the state religion to simply ignore or endure.

In March 297, Diocletian issued a decree against the Manichaeans (a Gnostic religion that combined Zoroastrian and Christian elements) as a new religion that broke the tradition of the Roman nation: “It is criminal to throw doubts on what has been established from ancient times.”

Between February 303 and March 304, Diocletian issued four decrees against Christians, first attacking worship and banning books and culminating with the demand that all inhabitants of the empire must offer sacrifice to the gods on pain of deportation or death. Historical evidence suggests that these edicts were vigorously pursued and that many Christians lost property, position, and life itself during the persecution.

Diocletian resigned the position of Augustus in 305, and his successors, Galerius and Maximinus Daia, waged a more ferocious persecution until the spring of 313. It was not uniformly imposed, but the pressure was continuous for a period of more than 10 years.

History of Christianity

The Reign of Constantine

In most respects, Constantine adhered to the same premise as Diocletian concerning imperial rule and religion.

First, he sought to establish a unified rule by making himself the sole Augustus. At one point at the beginning of 310, the empire had seven rival “emperors,” but Constantine worked ruthlessly to eliminate rivals and make himself sole ruler.

The real privileging of Christianity by the emperor Constantine became apparent with the practice of donating formerly pagan temples for use in Christian worship.

Constantine was born a pagan and only received Christian baptism on his deathbed, but from the beginning, he clearly favored Christianity as the new “glue” of the empire. Eusebius spoke of Constantine’s father, Constantius, as a believer in the one God but stopped short of calling him a Christian. It is possible that Constantine was drawn to the religion through the influence of his mother.

The ecclesiastical historian Eusebius reported the legend of Constantine’s dream before the Battle of the Milvian Bridge (“in hoc signo vinces”) in 312 and the placing of the Christian chi rho (the first letters of “Christ” in Greek) on his soldier’s shields.

After his defeat of Maxentius, Constantine and Licinius issued a decree of freedom of worship for the Christians in June 313, referring to an earlier mutual agreement at Milan in 312. Hence, this decree of toleration is called the Edict of Milan.

Constantine immediately used his supreme authority to become the protector and benefactor of the formerly persecuted religion.

He proclaimed release from exile of those who had been persecuted and the restoration of property to confessors, while property taken from churches was to be restored by money from the imperial treasury.

He issued benefits to African clergy of “the very Holy Catholic Church,” including exemption from taxation and performance of public service.

Beginning in 313, Christian symbols appeared on imperial coins; pagan symbols disappeared by 323.

The state recognized the decisions made by church officials as valid for the Christian community.

The church could legally inherit and bequeath property.

Constantine began the practice of donating pagan temples as Christian sanctuaries and the building of splendid new basilicas for the exclusive purpose of Christian worship.

The population of the empire was statistically by no means yet “Christian,” and as we shall see, “paganism” did not immediately disappear, but the actions of Constantine decisively placed the imperial power behind the church, with the expectation that the church would also support a “Christian” imperial power.

History of Christianity

The Founding of Constantinople

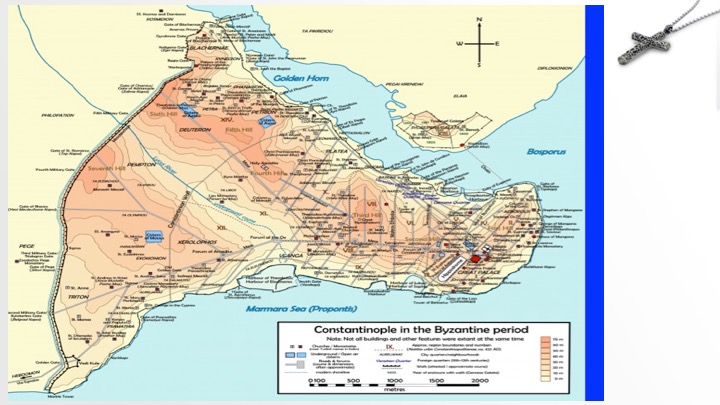

Constantine’s boldest and most important political (and religious) innovation was the founding of a “New Rome” in 330, which he named after himself: Constantinople.

Politically, Constantine recognized, as Diocletian had, the need to establish firm control over both the West and East, especially given that the West was under increased barbarian threat and the East faced the hostile Sassanid Empire.

He chose to make a new capital for the East at an ancient Greek city (Byzantium) founded in 667 B.C.E., then destroyed and rebuilt by the Romans in 198 C.E.

The location was ideal for purposes of security. Located on a peninsula extending into the Sea of Marmara at the Bosporus Strait, with the Golden Horn to its northeast, the city was supremely defensible. It repelled all invaders for more than 1,000 years, until the Muslims finally conquered it in 1453.

It occupied the join between Europe and Asia, with easy access by water for trade and the movement of troops. Constantinople formed the capstone of the prosperous economy and the predominantly Christian population of Asia Minor.

Symbolically, Constantinople was a New Rome that was also a Christian Rome from the beginning: Materials from pagan temples were used in its construction, and pagan idols were melted to provide gold for ornamentation.

In the future, Constantinople would become a genuine rival to the old Rome, thriving especially when the old capital was weak and challenging the old Rome for primacy in every respect.

If the first Rome was important because it was the seat of empire, then the new Rome must be at least equally important for the same reason.

But if the old Rome based its religious importance on being the city of Peter and Paul, then Constantinople should be secondary.

The seeds of considerable later religious distress were sown by Constantine’s political decision.

History of Christianity

Constantine and the Established Church

In the previous lecture, we traced the steps by which the Roman Empire turned from a persecutor of the Christian religion to its protector and patron. The personal religious convictions of the imperial patron, Constantine, were never entirely clear, yet he seemed genuinely devoted to the cause of Christianity. As head of state, he showed significant patronage to the Christian religion and referred to himself as the “servant of God,” but he never exercised the same direct control of Christianity that the Roman emperors had over worship in the empire. As we will see in this lecture, the efforts of Constantine’s successors to impose Christianity on the populace further indicate that the transition was neither natural nor easy.

Constantine’s Sponsorship of Christianity

Constantine’s personal religious outlook seemed to combine elements of superstition and syncretism. He was baptized as a Christian only at the last possible moment, on his deathbed. Further, the morality of his politics left much to be desired: He was as ruthless, indeed murderous, in pursuit of his ambitions as any other despot. Yet he seemed genuinely devoted to the cause of the Christian religion.

More significant, though, than his personal dispositions are the political actions Constantine took to secure the social and political peace of the empire through sponsorship of the once-despised “superstition.”

According to Eusebius, his biographer, Constantine wanted all to forsake “the temples of deceit” and enter “the radiant house of truth,” but he continued a policy of religious freedom for all, including freedom of public observance. He maintained the title of Pontifex Maximus and continued to issue some coins with polytheistic images.

With respect to Jews, the policy of earlier emperors had been to allow freedom of association among them but to forbid proselytism, or the conversion of Gentiles. Constantine maintained this position, but he forbade conversions to Judaism even more stringently.

As head of state, Constantine’s greatest innovation was the significant patronage he showed to the Christian religion.

The privileges of the old state religion began to be transferred: In 313, Christian clergy were granted exemption from military service and other public obligations.

In 321, Sunday was made a public holiday, and Christian images increasingly appeared on coins, military shields, and banners. Constantine also paid for the copying and production of 50 manuscripts of the Bible.

Pagan temples (such as the Pantheon in Rome) were made into Christian churches, and new basilicas (such as the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem) were constructed at imperial command and expense.

For members of the state apparatus, it became advantageous to make a public commitment to Christianity as a factor in career advancement.

Constantine referred to himself humbly as the “servant of God,” but he exhibited oversight of the church in the manner of the pagan emperors, terming himself “bishop of external affairs.” His was a difficult balancing act; as Pontifex Maximus, such emperors as Augustus had exercised direct control over every aspect of Roman religion, but Constantine did not have nearly that same control with respect to Christianity.

History of Christianity

Conversion in the Empire

The imperial favor of Constantine did not mean that the empire became immediately or totally Christian. Many places and many individuals kept older ideals and practices alive. Rural areas were particularly slow to convert to Christianity, but intellectuals did not capitulate easily either.

The famous rhetorician Libanius (314–394), a highly sophisticated and learned scholar, continued to defend traditional ways, even as he included Christians among his students. Among his orations is a Lamentation written in response to the destruction of pagan temples by Theodosius. Libanius also composed a magnificent eulogy for the emperor Julian, who had been one of his students.

As late as the 5th century, Augustine wrote The City of God (416–422) against pagan critics who claimed that the fall of the city of Rome was due to the abandonment of the pagan gods.

The efforts of Constantine’s successors to impose Christianity on the populace further indicate that the transition was neither natural nor easy.

In 341, Constantius prohibited all pagan sacrifice, an indirect confirmation that the practice must have persisted.

In 346, Constantius and Constans (337–350) issued an edict forbidding sacrifices and closed temples.

A Sicilian senator, Julius Firmicus Maternus, wrote a book called On the Error of Profane Religions (346), arguing for the forceful extermination of all pagan worship. But in 353–356, the imperial edict of 346 was renewed, a clear indication of its lack of complete success.

In short, the Christianization of the empire was an uphill battle. The final and prime evidence for this is the reign of the emperor Julian (361–363). Known by Christians as the Apostate, Julian was raised Christian as part of the Constantinian dynasty, but he converted to paganism and sought to restore the empire to its traditional polytheistic religion.

Trained in rhetoric and philosophy, Julian was lifted from his life as a student in Athens when Constantius II made him Caesar of the west in 355. He proved a more than adept soldier, and in 360, when he was acclaimed Augustus by his troops, he openly renounced Christianity.

When he became sole emperor in 361, Julian promoted a syncretistic form of religion, in which Jesus was honored with other great men who manifested the divine, and restored the pagan temples to their full functioning.

He removed Christians from high office and sought to return education to pagan standards. To please the Jews, he began the project of restoring the Temple in Jerusalem, but he did not persecute Christians in any active fashion.

It remains a fascinating historical question as to what might have happened if Julian had not been cut down in battle and his reign had lasted for decades.

Succeeding emperors quickly and decisively restored Christian privileges but continued to allow a certain freedom of worship. In contrast, the emperor Gratian (375–383) rejected emperor worship, removed the altar of victory from the Roman forum, discontinued state subsidy for pagan worship, and confiscated temple funds.

The decisive establishment of Christianity as the state religion of the empire took place under Theodosius I, who ruled the East from 379 to 392 and was sole ruler of both East and West from 392 to 395.

His edict “On the Catholic Faith” (380) imposed Christianity on all inhabitants of the empire.

He closed all temples, including the temple of Apollo at Delphi. Many of them he seized for Christian worship, and in 391, he forbade any pagan worship. In 392, he declared sacrifice to the gods to be high treason, punishable by death.

Theodosius I closed all pagan temples, including the Serapeum in alexandria and the ancient temple of apollo at Delphi.

Despite such repressive measures against paganism, Theodosius continued to maintain the right of Jews to assemble for worship. But in addition to not being allowed to proselytize, they could not enter into mixed marriages with Christians.

History of Christianity

The Effects of Establishment on Christianity

Official sponsorship of Christianity was a decidedly mixed blessing for the Christian religion, considered as religion. The positive benefits were obvious and on the surface.

Security from danger and persecution were an obvious good; being Christian was no longer a crime punishable by the state.

Political advantage to Christians extended from the occupation of magnificent buildings and land to an edge in bureaucratic advancement.

Above all, the opportunity was opened to expand the religion into a genuinely Christian culture.

The negative effects of establishment were less obvious but no less real.

As bishop of external affairs, the emperor involved himself directly in religious matters: The calling of councils was as much a matter of political prudence as it was of religious concern. The overriding issue for the emperor was the unity of the empire; religious divisiveness had to be resolved at all costs in order to secure political stability.

Thus, as early as 314, Constantine called the Council of Arles so that the bishops could respond to the Donatist schismatics’ appeal from their condemnation by the bishop of Rome. The council rejected the Donatists’ petition and condemned the North African movement.

In 325, Constantine not only summoned the first ecumenical (“empire-wide”) council at Nicaea (in Asia Minor) to decide the Arian controversy, but he actually presided at the opening of the council and provided its agenda.

Subsequent emperors aligned themselves with one party to a theological dispute or another and used the power of the state to enforce their will. Bishops, in turn, were all too willing to seek the imperial power in their support.

During the complex Arian controversy of the 4th century, the bishop of Alexandria (Athanasius) was repeatedly exiled and restored according to the doctrinal allegiances of Constantine II (337) and Constantius (339), neither of whom had any real conviction in the matter but tried to put their weight behind who they saw as the most likely winner.

Already in the 4th century, then, the lines of what would be called “caesaropapism”—the merging of imperial and religious power—were established.

With all of this in place we move next week into an examination of "The Spread of Christian Culture", in which we will how this now "official" religion" began to use the power it now had to dramatically expand the spread of a Christian culture across the Empire.

< Audio >

History of Christianity Class 6 - The Slides