History of Christianity - Class 3

Paul and the Gospels

Paul (Acts and Letters) and the Gospels

As a reminder, in our first class we reviewed the cultural mix that Christianity was born in. The Mediterranean world, the Greek culture and empire, the Roman Empire, and Judaism. And we suggested that in a sense Christianity had aspects of all of those cultures in its DNA. In our last class we reviewed the explosive growth of Christianity in its first 40 years over a significant part of the Roman Empire.

Today we will change emphasis a bit. As Christians we know that we need to understand the Apostle Paul and we know that we need to understand the Gospel books. Paul because of the important role he played as the Apostle to the Gentiles, which is where most of that growth came from.

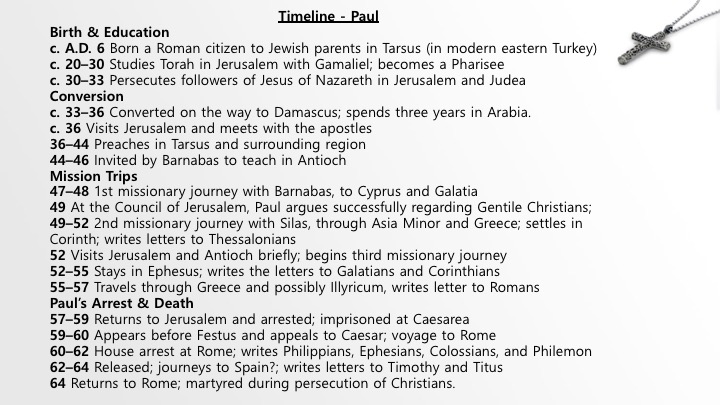

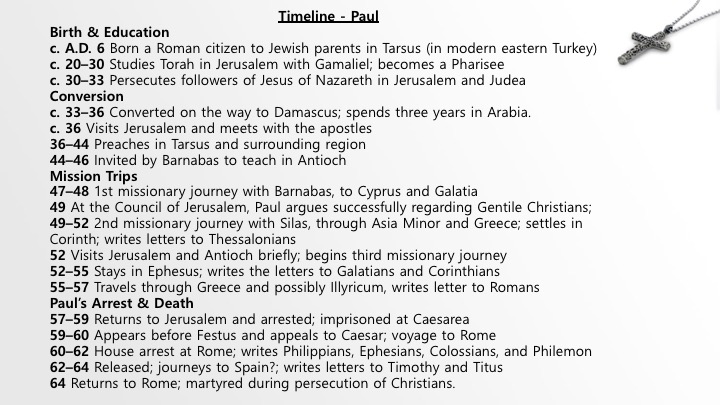

What do we actually know about Paul? As I mentioned last week almost all we know is what we find in the new testament - especially from the book of Acts and from Paul’s letters.

Introduction to Paul

During the roughly 40-year period of 30–70 C.E., three developments in Christianity occurred simultaneously.

Communities (churches = ekklesiai) were founded and nurtured in cities from Jerusalem to Rome; these communities had shared rituals, such as baptism and meals, as well as practices of preaching, prayer, and teaching.

In such social settings, oral traditions concerning Jesus were handed on in anecdotal fashion to legitimate and guide the practices of the community.

Leaders of churches, such as Paul, James, and the author of the Letter to the Hebrews, wrote letters to communities that were read aloud in the assembly.

Paul’s life is sketched both in Acts, where he dominates chapters 9–28, and in more fragmentary form in his letters.

Convinced by his Pharisaic convictions that Jesus was cursed by God because of his death (Gal. 3:13), Paul sought to extirpate the movement.

He had, in his words, an encounter with Jesus as Lord (1 Cor. 9:1, 15:8; Gal. 1:15–16; see Acts 9:1–9) that made him an apostle to the Gentiles.

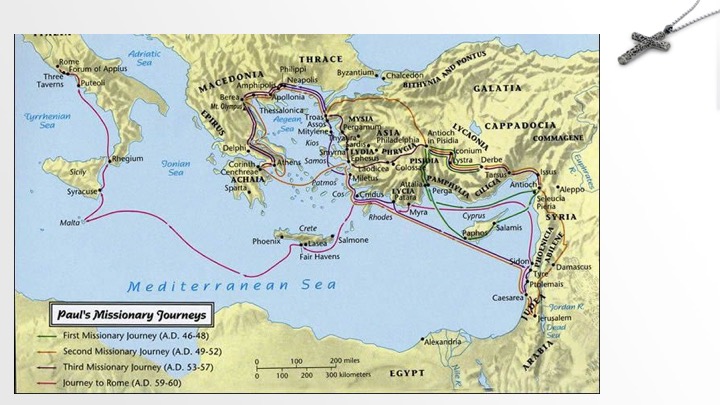

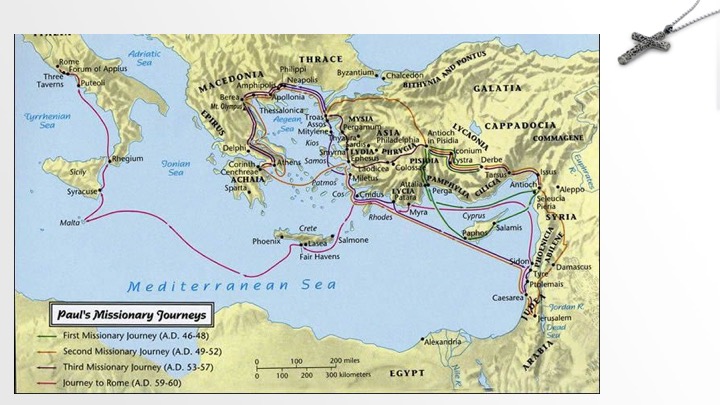

Apart from four to six years spent in prison, he spent the rest of his life founding communities in Galatia, Macedonia, and Achaia. He died a martyr under Nero.

Paul is important as a missionary of the movement, as a leader in the conversion of Gentiles, and as the first and arguably most important interpreter of the story of Jesus.

Scholars debate how many letters were written by Paul during his lifetime and how many after his death by followers, but the letters are nonetheless of unparalleled importance for what they tell us about early Christianity in the cities of the empire.

Introduction Paul (3)

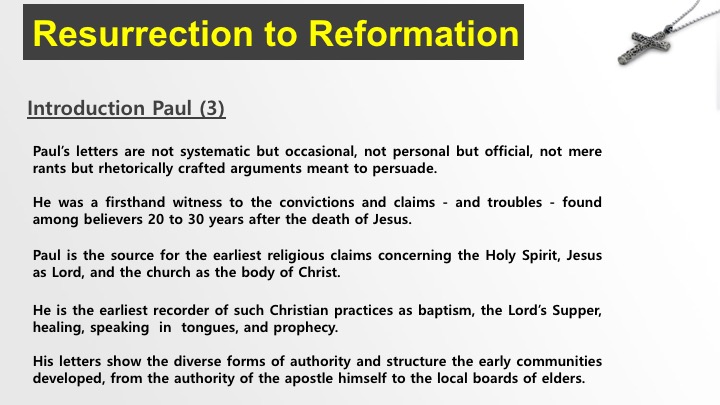

Paul’s letters are not systematic but occasional, not personal but official, not mere rants but rhetorically crafted arguments meant to persuade.

He was a firsthand witness to the convictions and claims—and troubles—found among believers 20 to 30 years after the death of Jesus.

Paul is the source for the earliest religious claims concerning the Holy Spirit, Jesus as Lord, and the church as the body of Christ.

He is the earliest recorder of such Christian practices as baptism, the Lord’s Supper, healing, speaking in tongues, and prophecy.

His letters show the diverse forms of authority and structure the early communities developed, from the authority of the apostle himself to the local boards of elders.

Paul’s Letters Reflected Tensions in the Communities

Paul’s letters open a window to a variety of serious tensions that challenged the first urban Christians and continued to haunt this religion through the centuries.

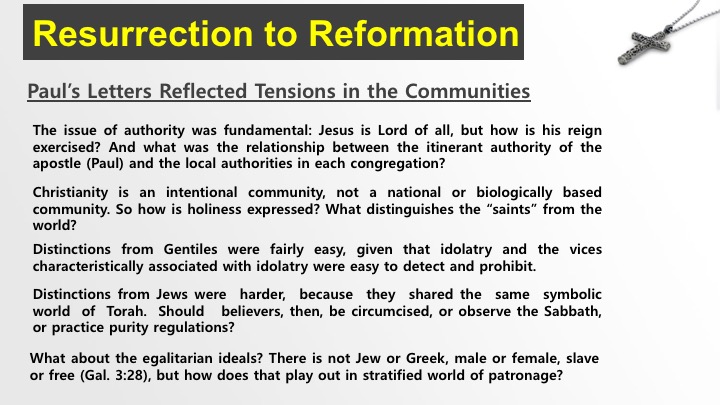

The issue of authority was fundamental: Jesus is Lord of all, but how is his reign exercised? Paul was sent as a delegate (apostolos) by God and the risen Christ, but his claims to authority were not self-validating or universally recognized. What was the relationship between the itinerant authority of the apostle and the local authorities placed in the church?

Becoming “God’s assembly” through conversion—this is an intentional not a national or biologically based community— demands “holiness,” but how is “difference” to be expressed? What manner of life distinguishes the “saints” from the “world”?

Distinctions from Gentiles were fairly easy, given that idolatry and the vice characteristically associated with idolatry were easy to detect and prohibit.

Distinctions from Jews were harder, because they shared the same symbolic world of Torah. Should believers, then, be circumcised, or observe the Sabbath, or practice purity regulations?

The assembly that meets “in Christ” has egalitarian ideals: There is not Jew or Greek, male or female, slave or free (See Gal. 3:26-29 below), but meeting in the stratified location of the household (oikos) meant complications for those ideals.

Egalitarian Ideals from Paul Galatians 3:26-29

26 You are all God’s children through faith in Christ Jesus. 27 All of you who were baptized into Christ have clothed yourselves with Christ. 28 There is neither Jew nor Greek; there is neither slave nor free; nor is there male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus. 29 Now if you belong to Christ, then indeed you are Abraham’s descendants, heirs according to the promise.

Did the Jew have an advantage over the Gentile? Why or why not? What did that mean for common table fellowship?

Did males continue to have supremacy in all matters or only those in the household? Did the Spirit represent a liberation for females?

If all are “brothers and sisters” within the worship assembly, why did that not change the social status of master and slave when the worship ended?

The rich should not be honored if poverty is the ideal, but rich members of the community served as benefactors. Should they not be leaders, as well?

The Vibrancy of the Early Christian Movement

Paul’s letters also bear witness to the vibrancy and energy of the nascent Christian movement as it exploded across the empire.

If early Christianity were simply the “Jesus movement” as a sect within Judaism, many of these issues would not have been raised; Jesus would simply have been another prophet or teacher. It was the power of the religious experience of the Resurrection that generated these great tensions.

Paul’s vision of the church as a “new creation” in which members are a “new humanity” in the “body of Christ” is a utopian conception of community that had great appeal, but it also had the capacity to disrupt the order of society.

Already in Paul’s letters, it is possible to see how Christianity forced open accustomed cultural values and began to reshape them—not all at once, never completely, and not always successfully, but it is difficult to account for Christianity’s appeal through the centuries without recognizing this power for social change as one of its elements.

The Diversity of the Early Christian Movement

Popular perceptions of Christianity’s first decades tend to be simplistic and distorting.

For example, some academic scholars have tried to argue that Jesus was the real “founder of Christianity” and that Paul distorted the Jesus movement because of his own views.

But this distorts by oversimplifying: There were many more players than just these two. Indeed, the Book of Acts itself places Paul in the midst of a larger and more complex movement involving many people.

Similarly distorted is the view that the first decades of Christianity generated a wild diversity of writings but that all the interesting versions were eliminated at the Council of Nicaea. There were other gospel accounts in addition Gospels, but none was earlier, and most were far from being more interesting.

Thus, the writings we have in the New Testament are, so far as we can tell, the earliest evidence for Christianity. Efforts to discover earlier “sources” within them, or to appeal to compositions from Nag Hammadi, or to cite fragmentary gospels as evidence for major movements are not convincing.

At the same time, many historians neglect the evidence of diversity provided by the canonical writings themselves. In addition to the 13 letters attributed to Paul are letters from James, John, Jude, Peter, and the anonymous author of Letter to the Hebrews; the four Gospels attributed to Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John; and the visionary composition called the book of Revelation, ascribed to John the Seer.

These writings (all composed before 100) predate any archaeological evidence for Christianity and amply testify to the diversity of experience, conviction, and perspective in the earliest decades of the religion.

The Other Than Paul Canonical Writings?

The importance of these other canonical writings, simply as historical sources, can scarcely be overstated. By their sheer existence as literature, they make clear that earliest Christianity was not represented only by Paul but by a variety of other leaders working in diverse communities. They also contribute additional evidence concerning the earliest movement beyond that offered by Acts and the letters of Paul.

In terms of geographical expansion, these writings speak of Jewish-Christian communities through the Diaspora (James); Gentile communities in Pontus and Cappadocia, as well as Asia and Phrygia (1 Peter); churches in Galilee, as well as in Judaea and Samaria (Mark, Matthew); and specific communities of Asia Minor in addition to Ephesus (Revelation).

In terms of political posture, they reveal a spectrum of attitudes toward the Roman Empire, from positive accommodation (1 Peter) to passive resistance (Revelation).

In terms of religious inspiration, the narratives of the Gospels, the poetry of Revelation, the rhetoric of Hebrews, and the prophetic voice of James alert the historian to the fact that the earliest decades of Christianity had vibrant and creative minds other than Paul’s.

The Four Gospels – Interdependence and Independence

The three Gospels called “Synoptic” (Matthew, Mark, and Luke) have a demonstrable literary interdependence. Similarities in language, material, and sequence require that such literary dependence take place at the level of written compositions: One was written first, and the others used it in their composition.

The majority of critical scholars conclude that Mark wrote first and Matthew and Luke used his Gospel as a source independently. Matthew and Luke also share material not found in Mark (often attributed to Q); finally, both Matthew and Luke have material unique to each.

In one sense, Matthew and Luke can be regarded as expanded (and, by their light, improved) versions of Mark’s Gospel.

The Gospel of John (the “Fourth Gospel”) makes use of material found also in the Synoptics but shapes the entire narrative so distinctively that no literary dependence on those Gospels is suspected.

The Gospel Portraits of Jesus

As interpretations of Jesus, the four Gospels offer distinct portraits; as witnesses, they converge on the character of the human Jesus.

Each Gospel portrays Jesus and his disciples in accordance with the evangelist’s social context, use of Torah, and literary goals.

In Mark, Jesus is the powerful son of God, whose proclamation of God’s rule is demonstrated by convincing deeds, yet as son of man, he is powerless before his enemies. Jesus is himself the “mystery of the kingdom” and the “parable,” and his disciples fail either to understand him or, worse, show loyalty to him. The drama of discipleship is central.

Matthew uses Mark’s basic plot and opens it to a conversation with formative Judaism—shaped by the ideals of the Pharisees and the techniques of the scribes—with which Matthew’s community was in conflict. Jesus appears as the fulfillment, the teacher, and indeed, the personification of Torah. Corresponding to the image of Jesus as teacher, the disciples, though no less faithless than those in Mark, understand the teachings they are to pass on.

Luke also uses Mark but extends his story to another complete volume (the Acts of the Apostles). Jesus is God’s prophet who reverses societal norms, heals, and associates with the marginal. In the sequel, his disciples live out his ideal as his successor-prophets.

John portrays Jesus as the man from heaven who, as the light, intersects the darkness of the world and calls it to conversion. His disciples are to continue his witness to the truth of God and will experience the same hatred from the world as Jesus did.

Despite such divergence in interpretation, the four Gospels converge in their understanding of the character of Jesus and of discipleship. They agree that Jesus is defined by an absolute obedience to God rather than by career, popularity, possessions, pleasure, or power: “not my will but your will be done.”

They agree further that this radical obedience is expressed through dispositions of self-giving to others: He “gives his life for others” and is “the servant of others.”

They agree that discipleship is a matter of “following” Jesus and exhibiting the same character of radical obedience and self-emptying love.

The Fundamentals of the Gospels

The Jesus shaped by the canonical Gospels has served as a fundamental norm for subsequent Christians—all the more powerful because it is cast in the form of story.

The realistic narratives enmesh Jesus in the world of materiality, time, history, and the goodness of human bodies; the Gospels stand against all efforts to make Christianity a timeless, bodiless, anti- institutional religion.

The Gospels also provide a Jesus who can surprise, shock, and challenge comfortable religious accommodation. We see that in the Sermon on the Mount. Christian reform movements have consistently appealed not to the “historical Jesus” but to the human Jesus of the Gospels who shaped subsequent history and continued to say “follow me”. ”Love God and love your neighbors”.

Every time I read the Sermon on the Mount I am reminded of the famous quote by G. K. Chesterson:

“The Christian ideal has not been tried and found wanting. It has been found difficult; and left untried.”

The Slides