History of Christianity Class 2

The Birth of Christianity

History of Christianity Class 2 - The Birth of Christianity

Last week we introduced our subject – The Early Development of Christianity.

We move today into the next subject – the birth of Christianity out of that complex mix of cultures of the ancient near east.

Last week we introduced our subject – The Early Development of Christianity.

The Three Phases – each of which will take several weeks to explore.

Phase I - the beginnings. Including a review of the mix of cultures out of which Christianity grew. Will continue into the early emergence of “the Jesus Movement”.

Phase II – how does Christianity become the Imperial religion and what are the consequences of that.

Phase III – the process by which popes, monks, and German kings formed a new society in Europe that was called Christendom.

So today we are still in Phase I and there is much to explore here.

Having sketched the cultural matrix within which Christianity was formed—the complex civilizations of Greece and Rome, built on Mediterranean culture and further complicated by empire, and the equally complex symbolic world of Judaism—we now turn to the Jesus movement and the birth of Christianity.

The metaphor of birth is particularly appropriate in the case of Christianity because it entered history at a specific time and place and with a definite parentage.

Like an infant, Christianity entered the world bearing the genes of Greco-Roman and Jewish cultures, but it combined those elements in a new and distinctive fashion, so that it was not simply a version of what had preceded it but something truly new in the world.

Let's first talk about the Founder of Christianity.

The Resurrection

According to the earliest Christian writings, Christianity did not begin with what Jesus said and did before his death. It began with experiences of Jesus after his death by his followers in a new mode of existence: As resurrected from the dead and exalted to God’s presence, Jesus is “Lord” and “Christ.”

Paul’s letters provide evidence for the claims made by the first believers, which are all the more startling because they were at odds with believers’ empirical circumstances.

First, believers claimed to have been saved; this salvation is not, in the New Testament, a future or a hoped-for state but a present reality.

Further, they claimed to be saved from negative conditions, such as slavery, law, sin, and death itself.

They believed they had been established in conditions of right- relatedness to God and other humans that could be described in terms of peace, joy, righteousness, and freedom.

Christians claimed an experience of ultimate power that transformed them. The symbol in the New Testament for this power is the Holy Spirit. The term “spirit” here refers to the nature of this power, which touches humans in their human capacities of knowing and willing. The term “holy” refers to the fact that the power comes from God, the Holy One.

This combination— that Jesus had been raised and that believers possessed the Holy Spirit—was the fundamental conviction and experience of the earliest believers and the birth of the Christian religion.

The early believers’ claim was not that Jesus avoided death, or lived on in some fashion in the memory of followers, or was resuscitated for a time. None of these equals “the good news.”

The gospel message (“the good news”) is that after his death, Jesus entered fully into the power and presence of God, that he was exalted—enthroned—to a full share in God’s own life. He is, therefore, “Lord”.

What Did Others Think?

That a human being had joined the divine realm as a “son of God” and was a lord and benefactor to humans would not have seemed strange to Gentiles.

To Jews, the claim that Jesus was a messiah was not theoretically a problem, but the claim that he was Lord made his followers appear as polytheists and, therefore, as heretics.

If the Resurrection of Jesus was the good news, his death seemed problematic to both Gentiles and Jews, appearing to disqualify him as a source of divine life for others.

In 1 Corinthians 1:18–25, Paul acknowledges that the “message of the cross,” which was for Christians the “power of salvation,” appeared to Greeks as foolishness and to Jews as a stumbling block.

In antiquity, the manner of death was proof of the quality of a life, and Jesus’s violent death by legal execution disqualified him as a source of divine life for both sides of the cultural world.

Crucifixion was the most shameful of all deaths, used mainly for slaves and rebels against the Roman order; the fact that Jesus died in this manner disqualified him as a source of divine life for both Greeks and Jews.

Paul says that the “Greeks seek wisdom,” meaning that a great soldier or sage could join the gods—but crucifixion, the most shameful of all deaths and one used mainly for slaves, could appear only “foolish.”

Paul further says that “Jews seek signs,”

meaning signs that Jesus was a genuine messiah for the Jews, but Jesus did

nothing to make things better for the Jews; he did not restore the kingdom, the

Temple, or the Law. In Jewish terms, he was a failed messiah.

The manner of Jesus’s life was that of a sinner; worse, his manner of death was one cursed by God, for “cursed is anyone who hangs on a tree” (Deut. 21:23).

A Complex and Tense Religion

From the time of its birth and earliest growth, Christianity was a complex and tension-filled religion.

Sociologically, it was underdetermined

and parasitic: Beginning as a sect of Judaism, it was expelled from the

synagogue and became a Gentile association (an intentional community) without

obvious boundaries.

Culturally, it was mixed, with a symbolic world shaped by a Judaism that was already Hellenized and with steady success among Gentiles rather than Jews.

Religiously, it made claims to an experience of ultimate power through the Holy Spirit that were cosmic but disproportionate to the actual situation of believers in the world.

The founding figure of Jesus? Was he cursed or the source of blessing? If he was Lord, then what does that mean for monotheism?

Many of the subsequent issues faced by Christians would involve the same tensions that marked the entry of the religion into the world and its first expansion.

We saw that the experience of power, even if from an unlikely source, was the distinctive claim made by the first believers. This power was not political, economic, or military but religious. The first believers claimed that they were touched by God through the Resurrection of Jesus. The persuasiveness of this claim to themselves and others must be the key to understanding how a failed messianic movement made its presence felt across the Mediterranean world within decades and with no other visible means of support. In this lecture, we’ll look at the rapid and mostly spontaneous spread of Christianity across the western empire from 30 to 70 C.E.

And we we now look at what we know about this rapid and spontaneous spread of Christianity. And our primary source of information is the book of Acts of the Apostles.

The Acts of the Apostles

The Acts of the Apostles was written circa 85 C.E. as the second volume of the Gospel of Luke, but it describes events from 30 to 62 C.E. It is the indispensable if also limited narrative account of the first expansion of Christianity.

Despite its obvious bias (it sees the movement as directed by God’s Holy Spirit), Acts is, by the standards of ancient historiography, reasonably reliable, given that it traces the stages of Christianity’s expansion from Jerusalem to Rome.

As archaeology and other ancient literature confirm, Acts gets its world right in considerable detail, including dates, locations, local leaders, and political processes.

Where it is possible to check Acts against other information, such as Paul’s letters, which to some extent overlap Acts 16–20, Acts gets the basic facts about the movement right, as well.

Acts (Issues)

The limits of Acts as a historical source are also real, requiring a careful and critical use of its narrative.

It is selective, focusing primarily on two leaders (Peter and Paul), on the westward rather than eastward expansion, and on cities rather than rural areas.

It does not have good sources in some instances. The first eight chapters concerning the founding of the community in Jerusalem contain little actual fact; as a good Hellenistic historian, Luke fills the gaps with impressive speeches and summaries.

It has definite biases. Acts emphasizes unity among Christian leaders, for example, as well as continuity between Israel and the new religion.

As an apologetic narrative that covers more than 30 years in 28 chapters (many of them consisting of speeches), Acts necessarily smooths over a much rougher course of events.

What Does Acts Say About the Early Expansion?

Supported by other early writings (such as the letters of Paul), Acts is a reliable source for certain aspects of Christianity’s first expansion.

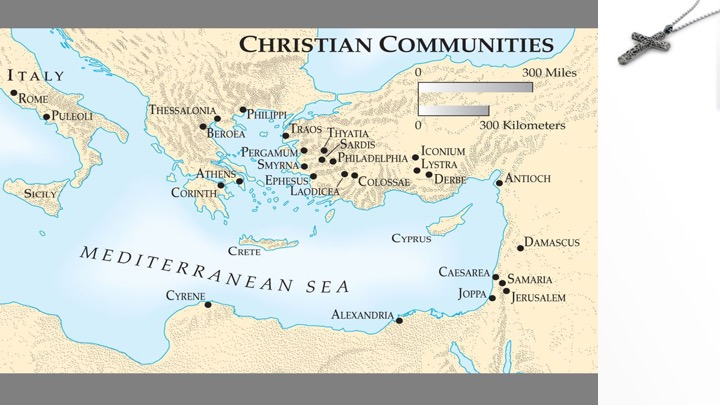

The expansion was amazingly rapid, its speed matched only by the spread of Islam, which had the advantage of arms and diplomacy. Within 10 years of the death of Jesus, there were Christian communities throughout Palestine and Syria; in 20 years, across Asia Minor and into Greece; and in 25 years, in Rome.

Let's look at a map of these early communities.

What Does Acts Say About the Early Expansion?

It spread through preaching in public but even more through personal contacts, such as the conversion of households and those Gentiles (called God-fearers) who frequented synagogues.

Note that converting a household had an entirely different meaning in New Testament time in the Roman Empire that is unfamiliar to us. We tend to think a household as a nuclear family - Father-mother-kids and the TV. In the complex social systems of Mediterranean Patronage a household could be 100 to 200 people. It may have a fairly wealthy Patron (the Father) at is head, along with his wife and children, and numerous kin (grandparent, great grandparent, uncles, aunts, 1st, second, and third cousins) as well as clients of many of those family members that lived nearby and did much of the work of the household. It often included slaves that did all the menial work of the household. When Acts cauusally mentions that Paul converted a household it might mean that 200 Christians were added to Christianity.

Also remember form last week's lesson that the God - Fearers (Gentiles who gather around synagogues because they were attracted to an attractive ancient religion (Judaism) were excellent places to convert future Christians.

Note also that he expansion of Christianity was carried out in conditions of duress. The movement spread not necessarily because people accepted it but at least in part because of harassment and even persecution, forcing early believers into frequent and difficult moves.

Christianity had to accomplish five transitions without a long period of stabilization and without strong institutional or textual controls.

(1) sociological, from a rural itinerant movement to an urban household association

(2) geographical, from Palestine to the Diaspora

(3) linguistic, from Hebrew and Aramaic to Greek

(4) cultural, from dominant Jewish institutions to dominant Gentile culture.

(5) demographic, from Jewish majority to Gentile majority.

The diversity found in the writings of the New Testament, in terms of genre, perspective, and argumentation, are rooted at least in part in the diversity of experience and circumstance of the earliest Christian communities.