Genesis as Literature - 9

How Do We Read Genesis?

As I am sure you have already figured out – I am much more impressed by reading Genesis holistically – as a literary whole – rather than reading it in a reductionist manner such as by creating the JEDP or documentary hypothesis. That reductionist approach is still the predominant theme among biblical scholars but, as I have mentioned too many times, is coming under attack, by a new group of scholars who see greater value in viewing Genesis through a literary lens.

So today we are going to try to briefly do just that - look at Genesis holistically and review some of the many literary techniques used by the author of Genesis. So let’s get started.

So what are we going to do today?

We will review some of the literary motifs used. We have referred to some of these as we read earlier but today we are going to present a summary view of that topic.

Then we show some of the literary devices that used in modern literature – but were first used in Genesis.

We will then examine how the entire book of Genesis is structured. Scholars use the term redactional structuring. That basically means the manner in which individual episodes in stories are assembled to create a literary whole.

And finally some thoughts on what

we might conclude from all of this.

Motifs are simply repeated themes that carry a message.

These are four we will

briefly discuss today

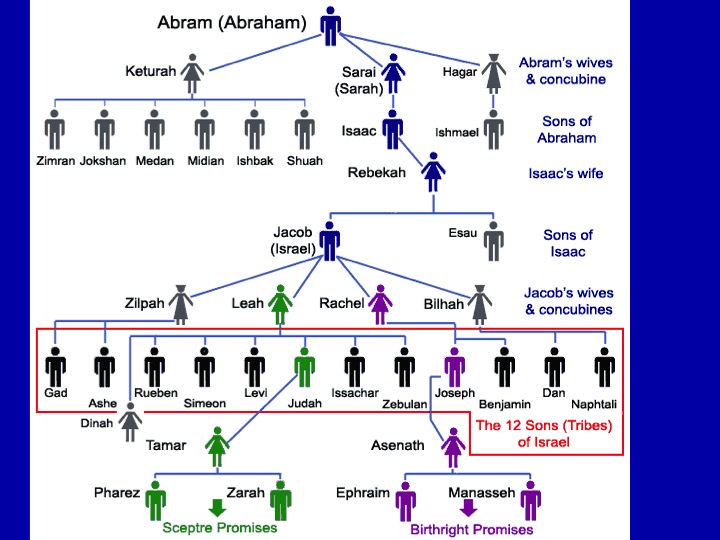

O.K. – when the game gets too complicated – you need a scorecard – here is ours. This is the growing family of Abraham. He had three wives – Keturah we know little about. Hagar had Ishmael – but for a major part of the Abraham story which we read Sarai was barren.

When she did have her son Isaac he married Rebekah, who was brought to him from the land of Aram. But Rebekah was barren. When she eventually conceived she had the twins Jacob and Esau (not identical). Jacob had two wives and two concubines and many sons – the 12 tribes of Israel. But one of his wives Rachel was barren - until she finally conceived and had her very important son Joseph. In each case God intervened to help the barren wife have children.

The second motif is the younger son. The ancient near east had a very strong culture of primogeniture – the oldest son inherits the family estate and is the most important. Yet time and again the younger son predominates in the Torah. Isaac supersedes Ishmael. In the next generation Jacob supercedes Esau. In the next generation Joseph rises to the top, even though he is 11th of 12 sons of Jacob. The other prominent son is Judah, who is one of the youngest sons of Leah.

So both of these motifs are very unusual. In the ordinary course of life in these cultures it is assumed that women have children and the older son inherits. So why does this continue to happen. There are two reasons. The first is a purely literary one – it is not the ordinary in life that makes for interesting narrative. These barren women and younger sons carry the story forward – generation after generation.

But the second reason may be theological. Women in the Bible represent Israel, based on a portrayal of the

lowly. The same is true of the younger son – another literary figure of the

lowly. And thus also represent Israel. Israel’s self image was one of a third

world nation – with poor resources – limited wealth – limited power. Only through the intervention of God do the

lowly prosper – that is to say – barren women give birth and younger sons rise

to the top. Thus it is with Israel –

only through God’s presence in Israel's collective destiny does this nation

prosper. The stories tell us that and these literary motifs tell us that.

We move on to literary devices now.

These are techniques that enhance a narrative and increase reader interest.

We have already covered maintaining conflict – those were the techniques used in the Abraham story – primarily the use of the conflict between God’s promises and the reality on the ground that Sarah was barren.

We will spend more time today

on the following two devices – the naming convention and style switching.

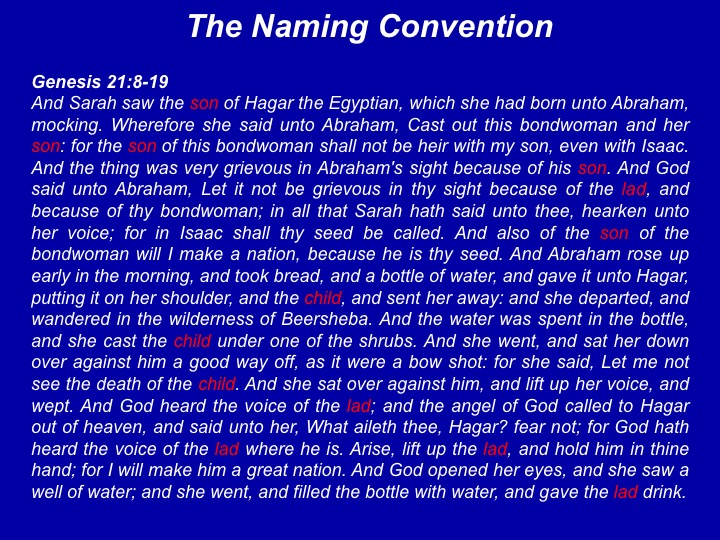

In many ancient traditions, including Jewish and Islamic ones, using or not using a person’s true name can be a powerful thing. The strength of this belief varies, and there are certainly exceptions to it. Nonetheless, the persistence and historical continuity of the linking of naming and power are unmistakable.

Genesis has a startling example of this in Genesis 21 – the story about Abraham and Sarah sending Ishmael away. As seen here in this extended text – suddenly the text stops using Ishmael’s name and instead substitutes the words son, child, and lad. Effectively the Genesis writer is signally to the reader that Ishmael is now being written out of the story.

Style switching or style shifting is a literary or artistic technique used when speakers or writers proactively choose different linguistic resources (e.g. dialectal, archaic or vernacular forms) in order to present themselves in a specific way or to impart a different meaning to a story.

The choice of linguistic style alerts the participants to the interaction of the context and social dimension within which the conversation is taking place.

This is a device used in

movies and books today. Recall World War II movies that switch scenes between

American and German Generals and when the Germans are on screen they continue

to speak English but pepper their language with well-known German terms (Herr

Commandant, Achtung, etc.) By use of this technique the moviegoer is

transported to a different language even though it is still English being

spoken.

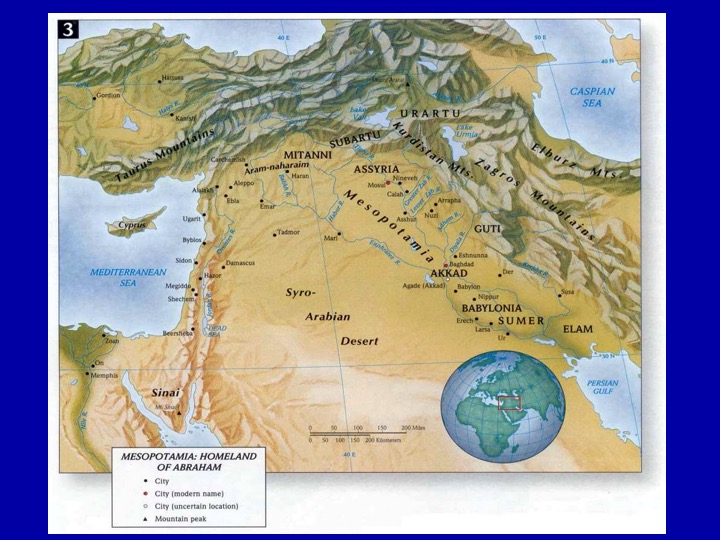

The writer of genesis used this trick twice – once in the entire chapter 24 and again in chapters 29-31. In both of these episodes a member of Abraham’s tribe visits Padam Aram – the ancestral home of Abraham. Padam Aram is in northern Mesopotamia and the language there is Aramaic – a Semitic language similar to Hebrew but different. And in the original texts (not our English versions) the biblical Hebrew is peppered with Aramaic words that the people of Israel would recognize – thus transporting the readers (listeners) to a new social context.

Such was the skill of the writer of Genesis.

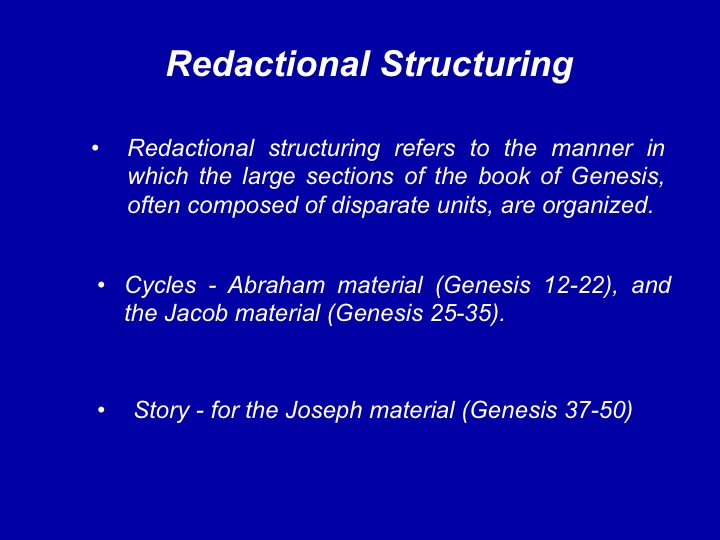

Redactional structuring refers to the manner in which the large sections of the book of Genesis, often composed of disparate units, are organized. We can see this literary technique at work in the three main sections of the patriarchal narratives: the Abraham cycle, the Jacob cycle, and the Joseph story.

We use the term cycle to refer to the Abraham material (Genesis 12-22) and the Jacob material (Genesis 25-35), because those narratives tend to be more a series of individual episodes in these characters' lives, with a connection between and among them not always readily visible.

We use the term story for the Joseph material (Genesis 37-50), because these chapters hold together as one long extended narrative, so much so that some scholars refer to the last section of Genesis as a novella.

All three redactional structures work the same way.

1. The cycle (or story) builds from its onset with a series of episodes in the life of the individual hero (the patriarch).

2. The cycle (or story) reaches a climax, or focal point, halfway through the narrative, on which everything turns.

3. The cycle (or story) concludes with another series of episodes, each of which matches, in reverse order, the episodes in the first half of the narrative.

We call this pattern with

inverse order of matching units chiasm or chiastic structure. You have already

been briefly introduced to it in the flood story, where I showed you the

chiastic nature of that short story.

Let’s briefly look at how each of these major cycles or stories are

organized chiastically.

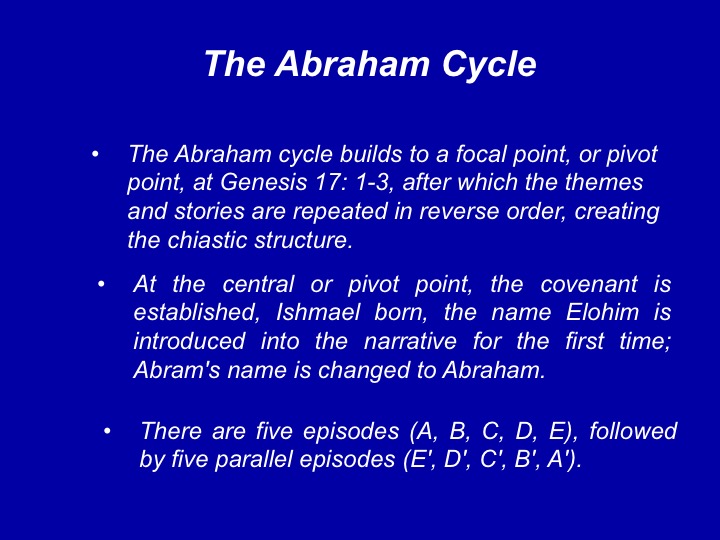

The Abraham cycle builds to a focal point, or pivot point, at Genesis 17: 1-3, after which the themes and stories are repeated in reverse order, creating the chiastic structure.

A. In Genesis 17:1-8, the name Elohim is introduced into the narrative for the first time; Abram's name is changed to Abraham; and the covenant is established.

B. There are five episodes

(A, B, C, D, E), followed by five parallel episodes (E', D', C', B', A').

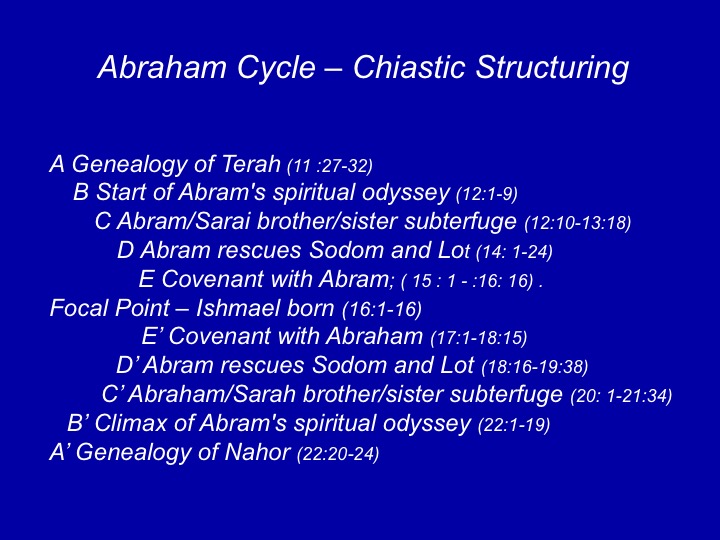

So let’s review the Abraham cycle first. Let me make an important point before we examine this – these chiastic structures are not easy to see in a long series of episodes such as the Abraham cycle – which stretches from the end of Genesis 11 to the end of Genesis 20.

The structure begins and ends with a genealogy.

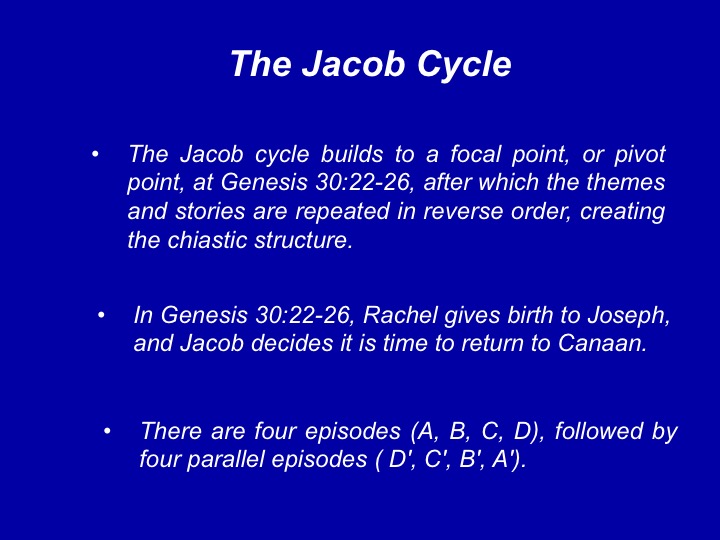

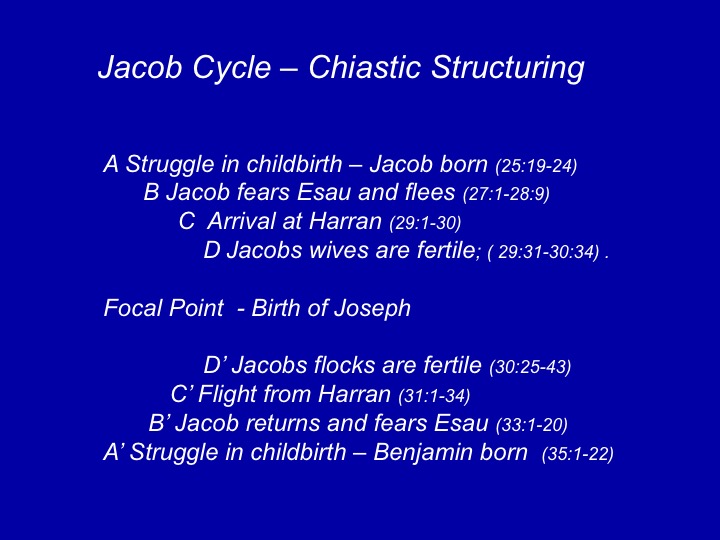

The Jacob cycle builds to a focal point, or pivot point, at Genesis 30:22-26, after which the themes and stories are repeated in reverse order, creating the chiastic structure.

A. In Genesis 30:22-26, Rachel gives birth to Joseph, and Jacob decides it is time to return to Canaan.

B. There are four episodes (A, B, C, D, E), followed by four parallel episodes (E', D', C', B', A').

I will not spend much time

analyzing the chiastic structure – because these things are actually kind of

tedious. it will be in the material posted on the web if you are a glutton for

tedium.

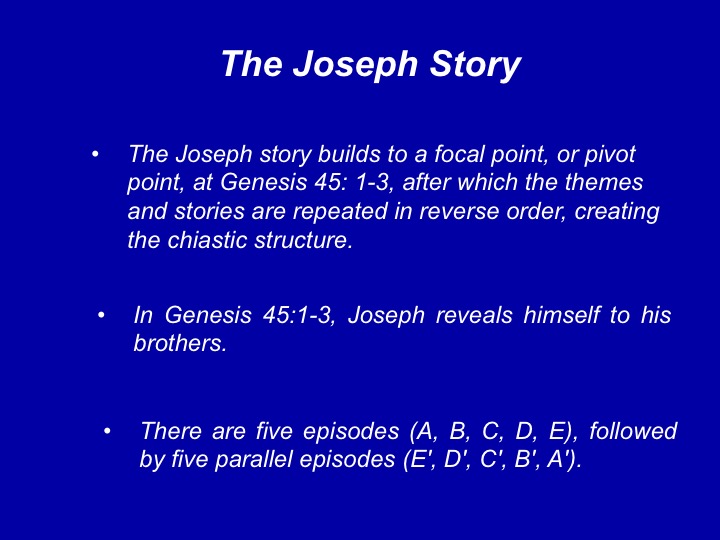

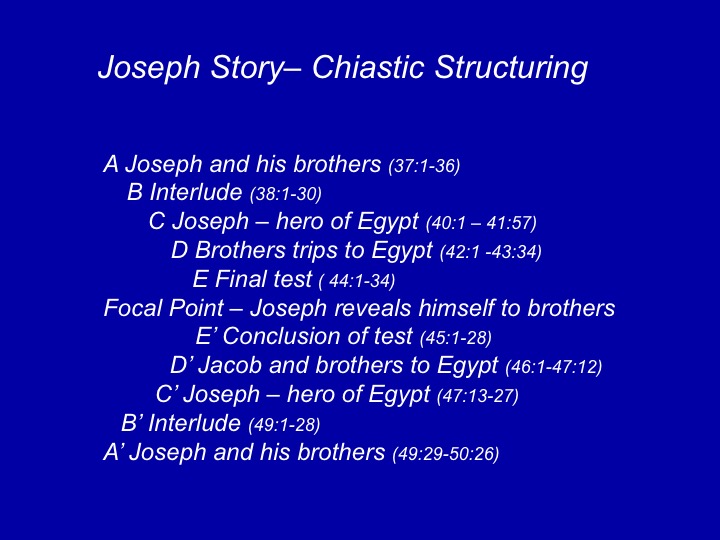

The Joseph story builds to a focal point, or pivot point, at Genesis 45: 1-3, after which the themes and stories are repeated in reverse order, creating the chiastic structure.

A. In Genesis 45:1-3, Joseph reveals himself to his brothers.

B. There are five episodes (A,

B, C, D, E, ), followed by five parallel episodes (E', D', C', B', A').

I will not spend much time analyzing the chiastic

structure – because these things are actually kind of tedious. it will be in

the material posted on the web if you are a glutton for tedium.

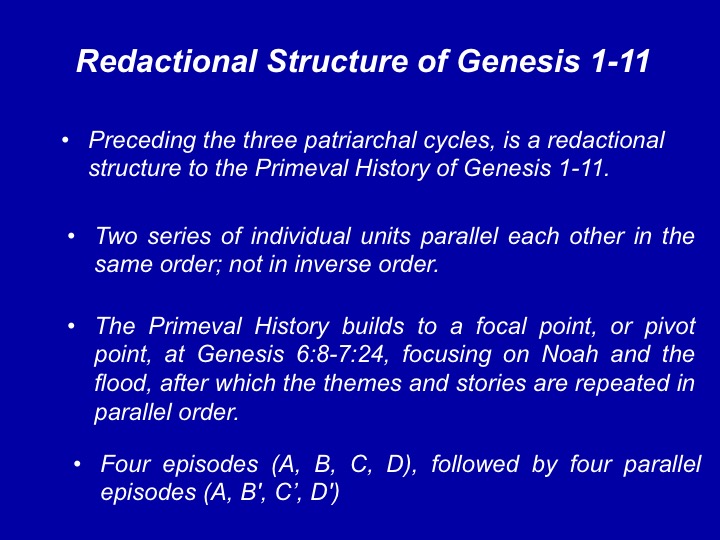

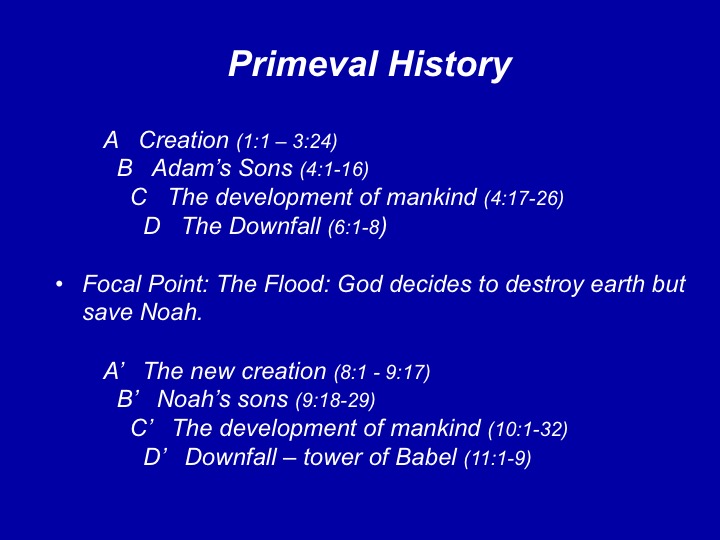

Preceding the three patriarchal cycles, there is also a redactional structure to the Primeval History in the first 11 chapters of Genesis, though the structure here is different.

A. The two series of individual units parallel each other in the same order; that is, they are not in inverse order or aligned in a chiastic structure.

B. The Primeval History builds to a focal point, or pivot point, at Genesis 6:8-7:24, focusing on Noah, after which the themes and stories are repeated in parallel order.

C. There are four episodes (A, B, C, D), followed by four parallel episodes (A, B', C', D')

Let's see how that works.

Here is that parallel structure for Genesis 1-11.8

The result of this analysis is the conclusion that there is much greater literary unity to the book of Genesis than most scholars have realized.

The reader is supposed to see the hand of God in this literary unity. A theological message shines through: There is a divine presence in Israel's history, with the redactional structuring serving as the blueprint.

Next week we will review my favorite part of the

book of Genesis – the novella of Joseph – and we will examine the Egyptian

aspect of it in light of our knowledge of Egyptian culture and history.