On Reading Genesis

Mike Ervin

Today we are not going to read from the book of Genesis – in fact we are going to spend the entire class period talking about how we might read the book of Genesis. Because how you decide to read something has a big impact on what you get out of reading it.

Genesis is the opening book of the canon for two major

faith traditions – Judaism and Christianity. It is part of what Judaism calls

the Torah, the first section of the Bible, the books Genesis, Exodus,

Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy. Also called the Pentateuch. As early as the 1st century AD

these 5 books were always found on one long scroll – indicating that they were

to be studied as a unit. And in both Judaism and Christianity there is unanimity

that these five belong together. Once you get past those first five the Jewish

and Christian canons scramble the remaining 34 books in different orders. In Judaism the Torah is accorded the highest

level of sanctity, above all other books of the Hebrew Bible. And Genesis is

foundational to the Torah.

This

course is, first and foremost, a course on the book of Genesis. In examining

Genesis we will need occasionally to look at other biblical material in the Hebrew Bible, but we will keep our focus on Genesis throughout. Because both the

Torah in general and Genesis in particular are so wide-ranging in

scope, we are going to look at it through a variety of lenses in order to

understand it better.

First point – Genesis is ancient literature. It was written almost 3000 years ago in a far away land, in a culture we do not really understand, in an ancient language called Hebrew that we are still learning about. And it was written in a narrative style. It is in a sense a collection of stories – stories most of us know very well because we grew up learning them. It is written in prose. The significance of that is all the other religious literature of the ancient near east was written in poetry. But the ancient author of Genesis rejected poetry as unsuitable for telling their story. So because it is literature we will try to bring literary analysis to the stories to help understand why they were told in the way they were.

Thus, we will bring historical analysis to the material, as we seek to uncover the history of ancient Israel and the surrounding cultures in the ancient Near East-that is to say, at times, the course will look and sound like a history course.

Genesis explains the worship of a single deity. Which was revolutionary in the ancient near east. But it also presents its ideas on the relationship of God to nature, to the human race in general, and to the people Israel in particular in ways that are, however, foreign to the expectations of most modern readers. It is therefore all too easy to miss the seriousness and profundity of its messages.

For the vehicle through which Genesis conveys its worldview is neither the theological tract nor the rigorous philosophical proof nor the confession of faith. That vehicle is, rather, narrative. The theology must be inferred from stories, and the lived relationship with God takes precedence over abstract theology. Those who think of stories (including mythology) as fit only for children not only misunderstand the thought-world and the literary conventions of the ancient Near East; they also condemn themselves to miss the complexity and sophistication of the stories of Genesis. For in that thought-world people tried to understand their world through the explanations of mythology – not modern science. These narratives have evoked interpretation upon interpretation from biblical times into our own day and have occupied the attention of some of the keenest thinkers in human history.

Related to this we will need to discuss aspects of ancient religion, ancient cult, and ancient theology - because ancient Israelites were completely surrounded by other religions on a daily basis. So at times, the course will look and sound like a religion course.

I said earlier that in reading literature the questions we ask can determine what we get out of it. I am going to suggest 3 questions we might ask as we study Genesis.

First - What was the author's original intent, and how did his or her original audience understand the text? This will be our main emphasis throughout the course. To successfully answer this question, we must immerse ourselves in the world of ancient Israel by attempting to live and think, as well as we can, like an ancient Israelite in, say, c. 1000 B.C.

Second - How has the text been interpreted by the two faith communities who hold the Bible to be sacred, namely, Judaism and Christianity, throughout the ages? This question requires a different approach, as we will illustrate with examples as we proceed. We should note that the formative periods of Jewish and Christian interpretation largely coincided: Jewish midrashic writings from the rabbis and early patristic writing from the church fathers both date to the late Roman or Byzantine period (4th through 6th centuries A.D).

Third - What does the text mean to me today? For me this is the Baptist Sunday School approach – because I grew up in a Baptist church and from about the age of 8 until about 12 or 13 I learned a lot about the stories of Genesis – and we tried to learn moral lessons from those stories.

We will focus on the first two questions and not the third.

To put some perspective on this question of what was the fundamental message of the book of Genesis I would offer this comparison.

Many

modern readers try to read moral lessons and lessons about how to be saved into

Genesis. But most scholars today are in

pretty strong agreement that Genesis was only about Revelation. The author or authors were trying to reveal

to the ancient Israelites the nature of their God and how their God was

completely different from the gods of all of the polytheistic religions they

were surrounded by. And also trying to reveal to them who they were and their

special covenant with the only God worthy of being worshiped.

It is important to understand how literature is experienced in older cultures. We do it by silent reading. In the ancient world it was a very different experience based on oral and aural transmission. The mouth and the ear. That experience puts a great responsibility on the writer, the reader and the listener.

One aspect of narrative in Genesis that requires special

attention is its high tolerance for different versions of the same event, a

well-known feature of ancient Near Eastern literature, from earliest

times. The book presents, for example,

two accounts of the creation, two of Abram/ Abraham's attempting to pass his

wife off as his sister (12.10-20; 20.1-18; d. 26.1-11), two accounts of God's

making a covenant with him (ch. 15 and 17), and two accounts of how Jacob's

name was changed to Israel (32.23-33; 35.9-15). In these instances, most modern

biblical scholars see different antecedent documents that editors known as

redactors) have combined to give us the text now in our hands. This could not

have happened, however, if the existence of variation were seen as a serious

defect or if rigid consistency were deemed essential to effective storytelling.

Rather, the redactors chose a different approach, refusing to discard many

variants as inauthentic or inaccurate, instead treating the different versions

as sequential events in the same longer story. The result is a certain measure

of repetition, to be sure, but the repetition is in the service of a

sophisticated presentation of themes with variations in a book rich in

narrative analogy, revealing echo, and suggestive contrast. For the Rabbis of

Talmudic times and their successors through the centuries, the exploration of

those subtle literary features provided an indispensable insight not only into

the first book of the Torah (the most sacred art of the Tanakh) but also into

the mind of God Himself.

The book is composed of four major sections: 1.1-11.26, the

primeval story; 11.27-25.18, the story of Abraham; 25.19-36.43, the Jacob

cycle; and 37.1-50.26, the story of Joseph. There is little independent

narrative about Isaac, the second patriarch.)

Next, there is the question of what translation to use.

The Revised Standard Version which comes in a variety of editions, such as the New Oxford Annotated Bible. This translation adheres closely to the Hebrew original, word for word.

The Jewish Publication Society Version is the standard among Jewish readers of the Bible. Note that it is a more idiomatic rendering and frequently departs from the Hebrew text literally. A fine recent edition, which includes this translation, is The Jewish Study Bible.

The most literal translation of the Torah, which of course,

includes the book of Genesis, is that of Everett Fox, professor at Clark

University in Worcester, MA. For those readers who wish to get as close to the

Hebrew text as possible, with the result that the English is often a bit

odd-sounding, this is the text for you.

All people who read a literature (or hear it being read to them) apply their cultural bias to what they are experiencing. We do that and the ancient Israelites did it.

There are many things they automatically “know” and we do not know. Some of the things written for that ancient culture can easily go right over our heads or worse confuse us. This is always a problem in reading about ancient ways.

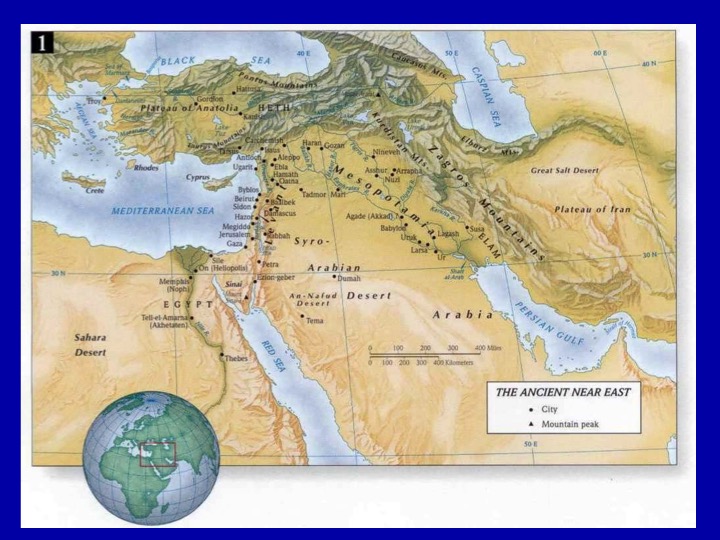

So let’s spend a few minutes today defining terms and talking about what the ancient near east is all about. So what does the expression “the ancient near east” actually mean. First of all we are using the term because that is the term that modern scholars use. What are they talking about?

The near east is the scholar’s

description for the region including Mesopotamia on the west, Egypt on the east

and the Land of Canaan in between. So

what does ancient mean in ancient near east.

Specifically it means the time period from 3000 B.C. to 330 B.C. Why 330 specifically? That is when Alexander the Great – the

military leader of Macedonia and Greece, conquered the ancient near east and

moved the scholars definition to the next great time period – the Greco-Roman

era. So the ancient period ends when the

Greeks conquered this entire area.

So how would we describe the ancient near east. Basically it could be described as two predominant world powers – Mesopotamia and Egypt, on either side of what could only be described as the third world – a weak collection of tribal peoples.

Now – we will cover the ancient near east in some detail in a few weeks. All I want to do today is comment a little about this region in the pre-biblical era. Because the story of the people of Israel in genesis starts up long after Mesopotamia and Egypt were world powers. In effect you should view the Israelites as very late comers to the ancient Near East. Both Mesopotamia and Egypt had thriving and literate societies in place 15 centuries before the Israelites appeared.

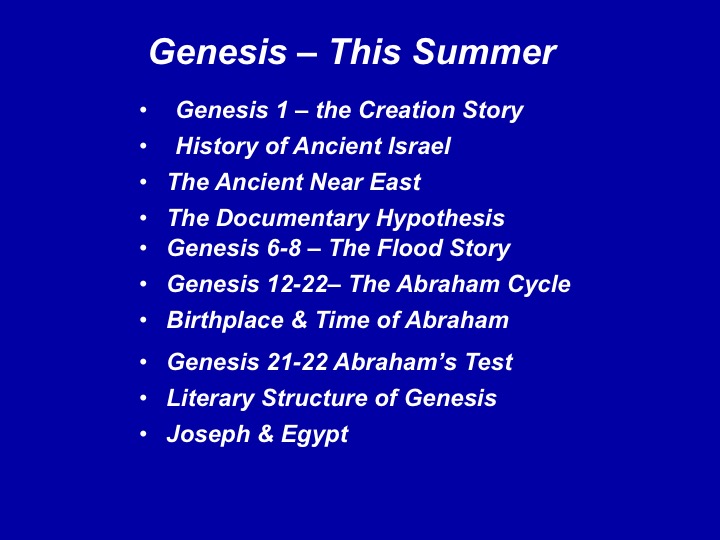

So we will be spending 10 lessons in this analysis of Genesis, beginning with the creation story, and following with first, a brief history of ancient Israel. and a brief history of the ancient near east. It is important then to try to understand the rather complicated Documentary Hypothesis - an attempt to intuit how Genesis was put together.

After that we will move into the stories and various interpretations of those stories. Toward the end we will take a fairly deep dive into Genesis as Literature, before we attack the novella at the end of Genesis on Joseph and Egypt.